Our Obama Era Cinema series continues with Caspar Salmon reflecting on the vitriolic online backlash to recent progress in Hollywood casting.

Just as Reagan had Die Hard and Bush had The Dark Knight, so America’s 44th Commander in Chief, Barack Obama, will come to be associated with specific films from the last eight years. So what exactly is Obama Era Cinema, and what does it reveal about the world we live in today? Have your say @LWLies #ObamaEraCinema.

What is Barack Obama’s prevailing moment, his defining characteristic? If George W Bush is remembered for the War on Terror, Bill Clinton for his impeachment trial, and Ronald Reagan for ‘Reaganomics’, then what is the one thing that we’ll take away from Obama’s presidency? I would argue that, after eight years of relatively stable government, and as a leader untainted by scandal, Obama still resonates most potently as the face on that ‘Hope’ poster – as a symbol of difference and change.

It isn’t that Obama has achieved nothing, more that his tenure has been characterised by an emollient nature, and perhaps a too conciliatory attitude to law-making, meaning that at times his avowed ambitions have felt misplaced, undermined, or oversold. The promise to close Guantanamo and the implied promise in his election manifesto to break with the war and pain of the previous administration, were not kept. If Obama seemed to mark a rupture with hawkish governments of the past, this was belied by his appointment of supporters of the war in Iraq, his hostility towards whistleblowers and his apparent fondness for droning civilians in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen.

And while Obama talked a big game about – and was visibly, genuinely harrowed by – gun violence and police brutality, he has been criticised for not speaking out more pointedly about institutional racism and racial inequality. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in The Atlantic in 2013: “As American President it is wrong for him to handwave at history, to speak as though the government he represents is somehow only partly to blame. Moreover, I would say that to tout your ties to your community when it is convenient, and downplay them when it isn’t, runs counter to any notion of individual responsibility.”

All of this requires scrutiny, and it is right that Obama be criticised for his record on these matters. But, returning to the poster of Barack Obama – the Shepard Fairey one that proliferated online and in a thousand home-made banners and other paraphernalia before and after the 2008 election – it is this which resonates most strongly today. Eight years ago, Laura Barton wrote that the image had already attained an iconic status comparable to that of Jim Fitzpatrick’s famous Che Guevara picture. What is truly remarkable is that the symbolism of that image – the symbolism of Barack Obama himself, a black man in the White House – is still so compelling. To say that the image of Obama is more important than what he achieved isn’t to do him a disservice: it is the greatest force of symbolism that it can transcend mere acts, and that Obama’s meaning is still so important and deserving.

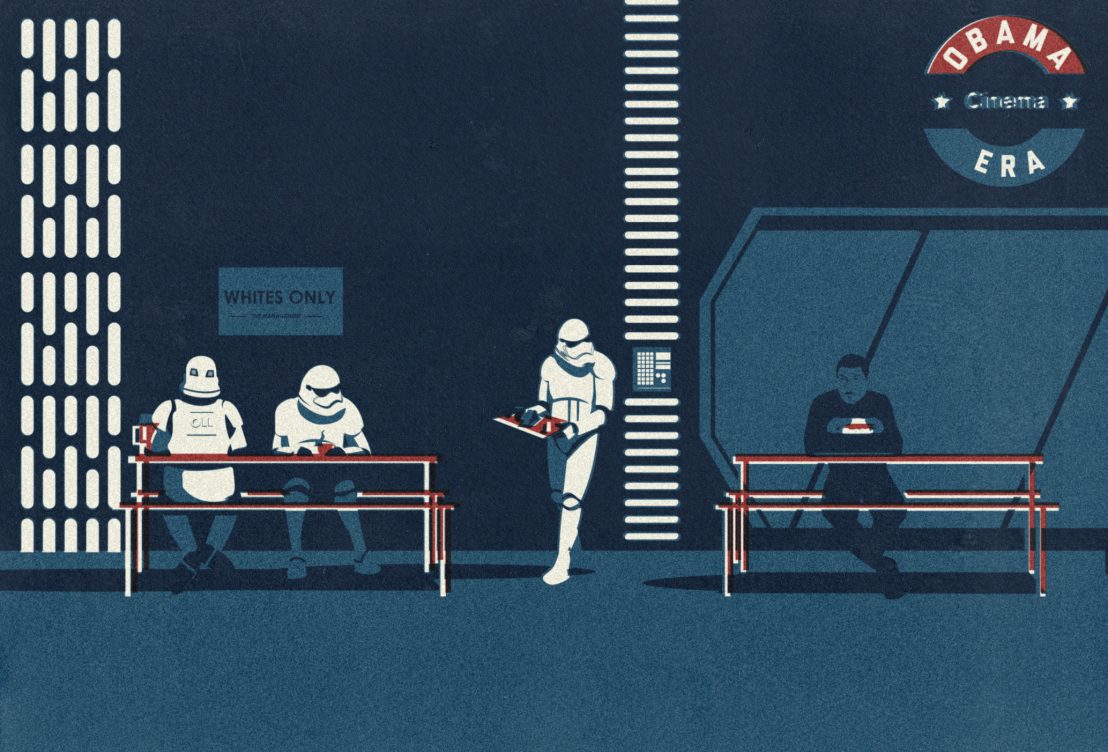

As in real life, so in cinema – so Obama’s presidency has been marked most acutely on screen by progressive symbolism, and offscreen by hot, toxic disputes as to the legitimacy of, say, casting a black man as an alien. When the trailer for Star Wars: The Force Awakens was released in October 2015, revealing British actor John Boyega as the first black Stormtrooper, a protest campaign was promptly launched on Twitter calling for a boycott of the movie. Under the hashtag #BoycottStarWarsVII, racist users who think that Chewbacca is a total legend vented their fury that someone in a different era on a different planet could be black.

A few years before this, when Idris Elba was cast as a god in Marvel’s first Thor movie, white supremacists moved to boycott it, with the Council of Conservative Citizens (CCC) lamenting that a mythological deity of yore might have the face of a black man. These events aren’t coincidental, and they speak of a greater disquiet since Barack Obama’s election among white, racist citizens, about the legitimacy of black empowerment.

In 2008, Donald Trump, before he started campaigning to put an entitled, white male egomaniac back in the White House, was among the leaders of the birther movement, which sought to question Obama’s legitimacy as president; in reality, the whole thing was an ugly facade behind which to rehearse and indulge in racist hatred, in which view a black person could never be entitled to gain highest office. The crux of the racist anger is to do with territorialism: in this narrow worldview, the Star Wars franchise, Marvel comics and the White House have all historically been ‘owned’ by white people. Nowadays, the CCC campaigns for Trump to be president. Meanwhile, Thor made $449.3 million at the box office and Star Wars: The Force Awakens is the third highest-grossing film of all time. The symbolism of this casting – what it means to make yourself the object of hatred, what it means to represent people of colour in a created world – speaks plainly.

Identity politics, often castigated for its negative impact online, in media, and in government, leads in these instances to something like the hope that Obama represents. During his presidency, the concept of the Bechdel test has gained greater traction, to the extent that while women are still gravely lacking onscreen, there is at least a conversation about the underrepresentation of women, and there are movements to celebrate and promote the work of women.

Geena Davis, who launched the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media a year before Obama came to power, founded the Bentonville film festival in 2010 to promote diversity. Elsewhere, the female cast of 2016’s Ghostbusters reboot endured the same sort of roasting from anonymous bigots as Boyega and Elba before them, with Leslie Jones the primary target of misogynoir activism online. That the film came out in the year that Hillary Clinton will become America’s first female president feels almost too pat – the symbolism is impossible to miss.

Also notable in cinema during Obama’s presidency, and arising from the sort of positive identity politics he stands for, is the rise of the #OscarsSoWhite movement, which sought to counter racist discrimination against black actors onscreen, and led to a public debate about awards going to white actors year after year. The conversation continues, rippling around film industries all over the world, with questions about black representation being asked in France, and prominent actors like David Oyelowo chastising the British film industry for not providing more roles for people of colour. Again, while the situation is not positive, the message sent by this activism, and by the championing of work by people of colour, can sometimes rise above the problem itself.

It seems likely that the realities of Obama’s administration will hit home in film sometime after he has departed: much as the war in Iraq came home to roost long after Bush had gone, we will only get the Black Lives Matter film that was presaged during the Obama era once the peaceful transfer of power has taken place. But something of the hope, of the need for change that he represented, hangs in the air.

Published 4 Nov 2016

By Vadim Rizov

Vadim Rizov considers the mainstream appeal of a trilogy of proudly racist films by one of conservative America’s most potent voices.

Take an exclusive look inside our latest print issue. Available now in a galaxy near you...

In our latest Obama Era Cinema essay, Stephen Winter considers the impact of two controversial role reversal fantasies.