“The whole world is watching,” sing the protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago as the end credits roll in Haskell Wexler’s 1969 film Medium Cool. The chants were fitting back then, just as they were on 21 January, 2017, when the Women’s March on Washington made the entire world take notice once again. Signs read “protest is the new brunch”, encapsulating a trend for mass participation in a modern world. Social media put everyone at the heart of the occasion; whether you were at a march or not, anyone could be vocal about a loud, proud political movement even if only in 140 characters.

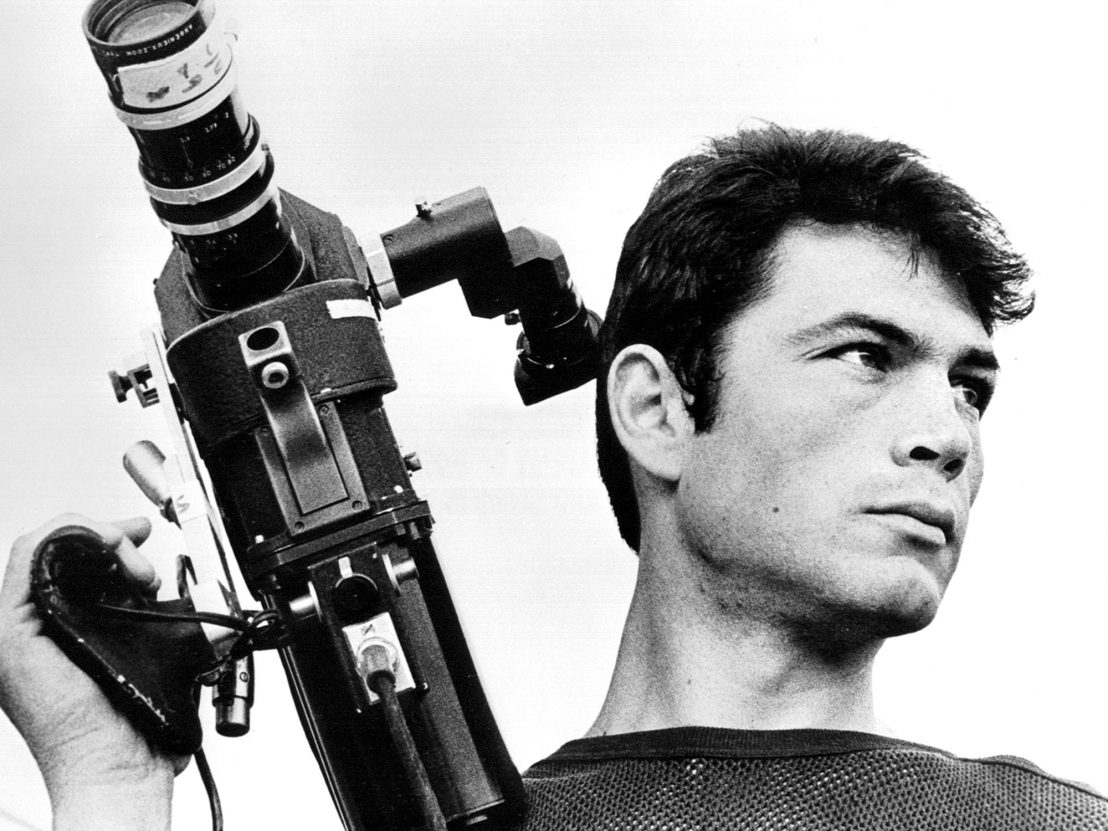

It was an event that thrived on a variety of new platforms, a statement about positive political engagement for a new generation. Medium Cool, a slick American drama about a TV news cameraman in the late 1960s, encourages that kind of participation through the evolution of a spectator character who moves out from behind the camera to become immersed in the politics around him. The ’60s counterculture that the film closely examines is documented through real protest footage, with scenes shot on location as events unfolded.

The truth seen on screen surrounds the audience and returns us to that nasty reality that the act of watching a film is meant to take us away from. The film questions ideas of both the ethics and politics of images within Wexler’s narrative for his lead character who “just loves to shoot film”, and is obsessed with capturing the news he finds in front of him. If you thought Jake Gyllenhaal’s bloodthirsty cameraman in Dan Gilroy’s Nightcrawler was unique, Wexler’s protagonist John Cassellis (Robert Forster) is essentially that character’s kindred spirit.

In the 2014 thriller, Lou Bloom chases crime scenes across Los Angeles to capture the bloodiest footage for TV news stations in the, obeying the broadcasting mantra “if it bleeds, it leads”. Cassellis maybe wouldn’t agree entirely with Bloom’s tactics, but if Medium Cool’s opening scene is anything to go by, he would probably understand his intentions. Video camera resting on his shoulder, sound guy following closely behind, Cassellis snoops around a wrecked car on a Chicago highway and its severely injured driver to capture the accident before remarking on a leisurely walk back to their car, “better call an ambulance”. It’s an alarming scene that highlights just how blind he really is behind the camera, with human safety taking the second spot on his list of priorities.

The cameraman gradually grows disillusioned with his craft and the film’s turning point ignites his moral outrage and his understanding of the role he has played in an oppressive system. He turns to freelancing, and the DNC protest provides a clear opportunity to capture an expression of resistance and reclaim his work. Both the film’s story and the director’s approach pose interesting questions – Cassellis rejects the position his job puts him in once he realises how the footage can be manipulated, but it’s the power of the right footage that makes Medium Cool so effective and important.

Wexler’s protagonist and his cinema audience learn to see what is real in a push towards political engagement and social activism that the Women’s March also encouraged. In rejecting his position as a passive spectator, Cassellis understands the power of the camera that the filmmaker has capitalised on throughout.

Despite bringing us back to the real world, it begins to feel like we are eventually going to be lost in the narrative realm of the film. The young Robert Forster is ruggedly handsome and Eileen (Verna Bloom), the single mother he befriends, is wholesome and relatable with a sweet yet troubled son. Perfect romantic family drama material it would seem.

Medium Cool is also simply beautiful, the result of having a famed cinematographer – Wexler previously shot In the Heat of the Night, The Thomas Crown Affair and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? – as its director. The film moves from sun-drenched, golden scenes of familial happiness as Cassellis, Eileen and her son spend an afternoon together watching pigeon racing, to the bold purples and blues of the Chicago ghetto where he is chasing a story.

As attractive as it is socially aware, Medium Cool ultimately relies on the use of real documentary footage to make a clear statement on Cassellis’ sense of responsibility to depict the truth on screen. The romantic plot and cinematography is a beautiful trap, lulling us into a false sense of security. The audience, believing themselves to be merely spectators to a drama, become part of the political situation around them. This is as close to real life as it gets, and as such there’s no escaping it.

Published 20 Feb 2017

By Tom Bond

From Network to Nightcrawler, cinema has a long history of exposing television’s rotten core.

Movies have always reflected social attitudes and trends – and that could prove especially vital over the next four years.

By Thomas Hobbs

The director’s satirical 1994 horror explores what happens when society embraces its worst monsters.