Romantic comedies traditionally skew heavily towards the perspective of the protagonist, which often triggers thin characterisation of the opposing male or female character of the story. The clichéd archetype of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl comes from the male point-of-view, where a female character is given little or no depth beyond being quirky and desirable.

Alternatively, male love interests in female-led rom-coms are often charming everyman types who are overlooked until the time when our heroine realises the love of her life has been hiding in plain sight the entire time. It’s rare that we get to see a perfect split in relationship terms, where two characters are allowed to develop as individuals before they come together as a couple. The genre has a longstanding bad habit of compartmentalising people.

Netflix’s Love is a series that excels by slicing a relationship clean in half, revealing the fleshed out male and female perspectives at its core.

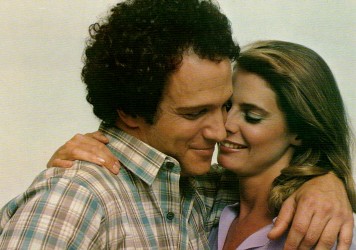

It tells of the burgeoning relationship between Gus (Paul Rust) and Mickey (Gillian Jacobs), who begin to date but quickly arrive at the realisation that they don’t quite work together. Los Angeles is the backdrop and the show relishes taking satirical snipes at Hollywood, where Gus works as a tutor for a child star (Iris Apatow, daughter of Love co-creator, Judd). Mickey produces a radio show that offers relationship advice from a psychologist (Brett Gelman) who thinks he has all the answers to her personal problems but really just makes everything worse.

Love is the brainchild of Rust, Apatow and Lesley Arfin, and it has a lot in common with Apatow’s previous television work – imagine what might have happen to the characters of Freaks and Geeks if they grew up and moved to LA. It has the modern millennial slant of Girls only without the navel gazing, with its derision of the entertainment industry marking it as a distant cousin of The Larry Sanders Show.

Under normal circumstances we might yearn to see a smitten couple together as much as possible, but Love balances the lives of Gus and Mickey so well that it’s just as gratifying to watch them in their daily lives. Love pulls us into the orbit of Gus and Mickey’s professional and social lives so that we get a sense of where they’re coming from when they meet. Early on in the first season it’s revealed that Gus has a tendency to awkwardly sabotage attractive opportunities that come his way, while Mickey’s various addictions repeatedly throw her life into chaos.

Crucially, we get to see the best and worst of these characters before the sparks start flying. It’s not a surprise when they bond over their grievances or clash because of a minor disagreement – we’re getting the know them at the same pace at which the narrative requires them to click. This is especially important in Mickey’s case, because all too often the female protagonist’s perspective is neglected in shows such as this. Just look at the way Cobie Smulders’ Robyn is frequently suffocated by the dominant male perspective of Josh Radnor’s Ted in How I Met Your Mother.

Balance matters when telling these kinds of stories, not least because it allows us to form a cohesive understanding of the halves that make the whole. By striking a more even, nuanced perspective between its two romantic leads, Love captures the rare thrill getting to know someone, and eventually loving them, in a more authentic, natural way.

Published 10 Mar 2017

Kaitlin Olson’s walking catastrophe is a welcome shock to the sitcom system.

The actor/director’s 1981 rom-com is one of the best films ever made about jealousy and self-loathing.

Television is now more direct, factual and unabashed than ever in its reflection of our toxic social climate.