Mothering Sunday, Eva Husson’s adaptation of Graham Swift’s 2016 novel about the slow, shattering griefs wrought by World War One on a village, is a largely melancholy viewing experience. The exception is one glorious sequence in which a housemaid saunters naked through a library.

The entire film takes place on Mothering Sunday in 1924, when Jane (Odessa Young), sneaks off for a tryst with her lover Paul (Josh O’Connor), the only surviving son of an upper class family who live on a neighbouring country estate.

Barely pausing for the sweat to cool from the sheets, Paul rushes away afterwards to meet his fiancé for lunch, leaving Jane the run of his vast house. And so, like a model for a Pre-Raphaelite painting (she is wearing nothing but her exceptionally long hair, liberated from its usual pins), she explores: running her figures along the exotic murals, tucking into a hefty meat pie she finds in the kitchen, and then, finally, entering the library.

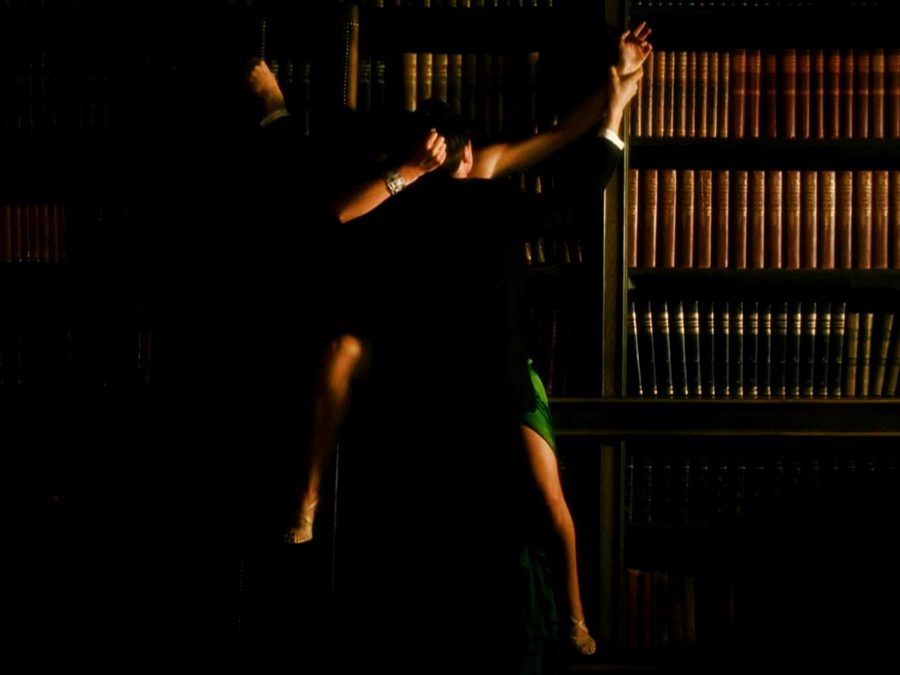

What accounts for the eroticism of the library on screen? It has served as a backdrop to some of cinema’s most sexually-charged encounters. The most explicit is probably an emerald evening-gowned Keira Knightley’s steamy – and ultimately tragic – encounter with James McAvoy in Joe Wright’s 2007 film Atonement, which undoubtedly inspired the rather less polite sex scene in Netflix’s smash-hit regency fantasy Bridgerton.

In Atonement, the very inappropriateness of the library as a setting for sex is what gives it its charge. The library is the antithesis of the bedroom: it is quiet, orderly, devoted to the mind, not the body. It is full of inanimate objects, the fragments left behind by the dead – there is nothing vivacious or alive about it as a space. Libraries ache with politeness. Which is exactly what makes them so attractive as settings for something as rude, as brash, as noisy as coitus. There is nothing sexier than transgression.

That’s why romances set in high schools so often include a library scene – stolen glances over textbooks are catnip to teenage hearts. Remember Heath Ledger peering hopefully at Julia Stiles through the gaps in the feminist theory section? Or Hermione whacking Harry with a heavy volume as lovestruck teens bat their eyelids at him from behind the Hogwarts bookcases? There is also, of course, the fear of getting caught: in Atonement, it is the desperate quietness and odd stillness of the lovers’ encounter that gives it its power.

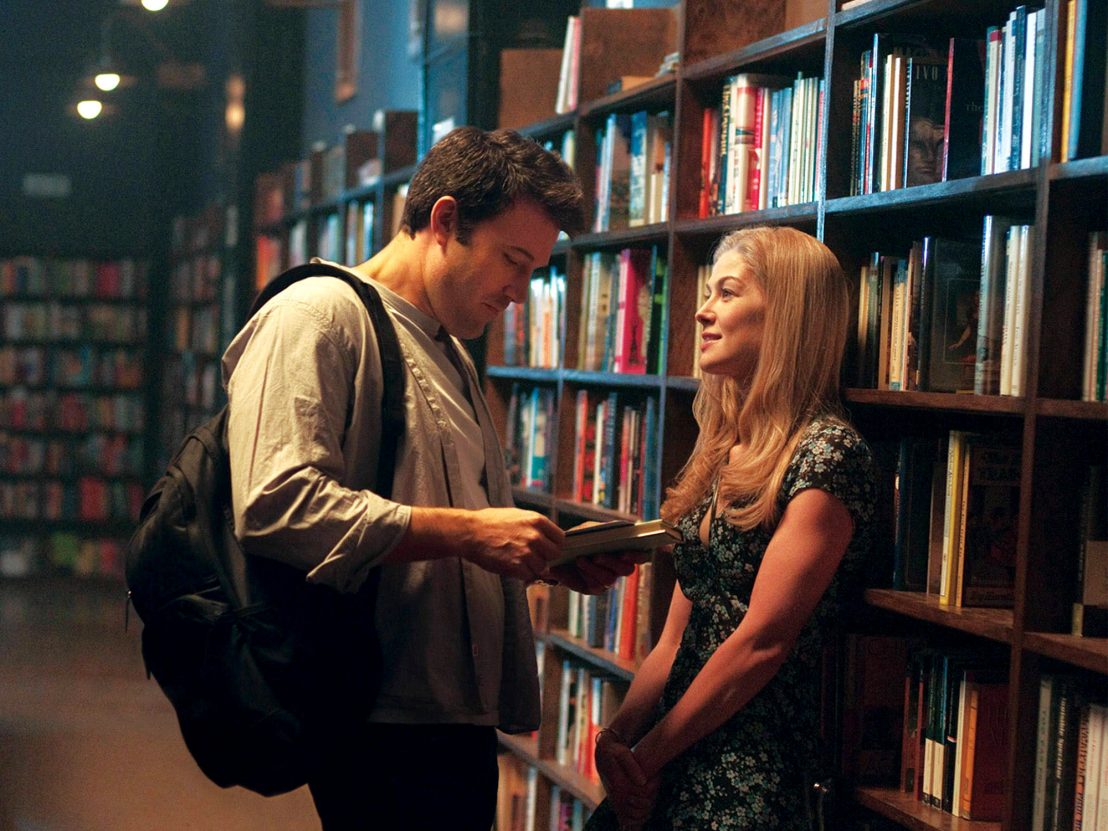

Of course, Wright was not the first director to see sparks among the dust and cobwebs. Sometimes, the intellectualism of the space fuels chemistry or game-playing: think of Nick and Amy’s anniversary treasure hunt in Gone Girl, leading them to Jane Austen, a shared sense of literary intimacy, and sex.

Cinema has long explored the potential of libraries not just as spaces for straightforwardly erotic encounters, but for moments of sexual expression and self-realisation. In The Breakfast Club, the library begins as a prison: it’s where the four teen protagonists are forced to spend their Saturday in detention. But by the end, it’s a dance floor – one on which each of the four breaks free of the constraints of the rigid school identities – as Karla DeVito’s ‘We Are Not Alone’ blares through the sound system.

Again, the power lies in contrast. Visually, the space is rigid, delineated by the sharp angles of bookcases and desks. The endless vertical lines of book spines almost look like prison bars. So watching Molly Ringwald shake her perfect red hair into a hedgerow and her classmates turn a bannister into a dance beam gives more pleasure than the obvious joy of the scene: it is the catharsis of broken rules.

As Jane, with her ambitions of becoming a writer, pauses in a space where she absolutely should not be – too working class, too female, too naked – the viewer gets a vicarious rush of the thrill she must be experiencing. There’s a naked woman in the library. No wonder the camera can’t look away.

Published 11 Nov 2021

By Lena Hanafy

Joe Wright’s World War Two-era romance is a beautiful story of a young couple torn apart by fate.

By Ella Kemp

Eva Husson’s English-language debut is a watered down adaptation of Graham Swift’s eponymous novel.

Inspired by The Shape of Water, we survey the various ways female self-pleasure has been portrayed.