This year marks the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong New Wave auteur Stanley Kwan’s queer classic Lan Yu, which premiered at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival and proceeded to take top honours at the Hong Kong Film Awards and Taiwan Golden Horse Awards. Due to the film’s explicit depiction of homosexuality, it has never been released theatrically in mainland China, achieving its cult status thanks to online piracy. This month the CineCina Film Festival will premiere the film’s 4K restoration at the SVA Theater in New York, (re)introducing audiences to an arthouse masterpiece.

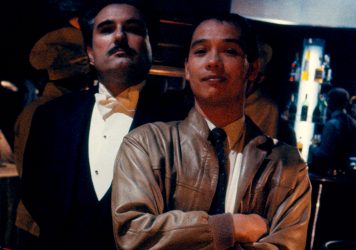

Adapted from an anonymous author’s homoerotic web fiction titled ‘Beijing Story’, Lan Yu is a poignant, heart-wrenching love story between two men in a time of economic reform, class struggle and civil unrest. Backdropped by the noirish urban landscape of Beijing during the late 1980s and ’90s, the film chronicles the on-and-off relationship between Lan Yu (Liu Ye), a financially struggling architecture student, and Chen Handong (Hu Jun), a closeted business mogul. Not only has the film been hailed as a milestone in Chinese queer cinema, it is also the pinnacle of Kwan’s aesthetic vision.

An internationally lesser-known phenomenon in China’s entertainment industry is that pseudo-homoromantic streaming shows are definitively mainstream and tremendously lucrative. Since the early ’00s, the niche genre of queer web fiction, which combines erotica and melodrama, has gained popularity among LGBTQ+ and female readers. With young women now the predominant consumers of pop culture in China, film and television companies are actively seeking out web fiction source material to adapt. The original homosexuality, however, is rewritten into homosociality for the screen to circumvent censorships and qualify for wider broadcasts and releases.

Chinese streaming giants have used this formula to produce The Untamed and World of Honor, the most watched shows in China over the past couple of years. This has led to the exploitation of the show’s queer and female fandoms, as the straight lead actors are encouraged to engage in homoromantic publicity stunts. Backdropped by the growing commercial hype around web fiction, Lan Yu was in this sense the first of its kind – a web fiction adaptation created by a team solely dedicated to their craft.

Chinese queer web fiction is quintessentially characterised by emotive aestheticism – de-emphasising narrative, sensationalising dialogue and romanticising scenarios. ‘Beijing Story’ was therefore the perfect source material for Kwan to further experiment with his poetic film language. It was also a timely opportunity for him to explore the subject of homosexuality, which was especially personal for him as the most high-profile openly gay director in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Though Lan Yu’s narrative is seemingly linear, Kwan uses episodic editing to compress the passage of time in the film, rendering Lan Yu and Handong’s decade-long gravitational push-and-pull as an ethereal wet dream. While it doesn’t have the homoerotica of ‘Beijing Story’, Kwan’s film is still a deeply sensual viewing experience, with the male characters’ bodies bathed in soft light and intimately framed. In turn, the couple’s carnal instincts accentuate the innate melancholy of their fatalistic romance.

There is a persistent misconception that the title character’s death was added only for shock value. But his death is symbolic, an indictment of the social stigma and political persecution that dooms his love. Consciously idealising the couple’s romance only to destroy it, Lan Yu remains an affecting counterpoint to the heteronormativity of Chinese media.

For screening info visit cine-cina.co

Published 7 Sep 2021

By Ian Wang

Po-Chih Leong’s 1986 feature, the first by a British Chinese director, was a landmark release. So why has it been largely forgotten?

Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film, newly released on Blu-ray, is a poignant and powerful love letter to the cinema.

Cocteau Twins’ Simon Raymonde and The Cranberries’ Noel Hogan reflect on the musical legacy of Wong Kar-wai’s 1994 film.