Is it cinema? Or is it supposed to be like an art installation? Why is a giant baby floating through space? These were some of the questions flying through Max Richter’s head when he first watched 2001: A Space Odyssey as a teenager. But even though the film’s highly subjective plot, which is centred around a mysterious monolith guiding humanity through pivotal moments on its evolutionary path, leaves more questions than answers, the German-born British composer was certain that director Stanley Kubrick’s use of classical music was groundbreaking.

“I was already studying the piano but watching 2001 really consolidated my love for classical music,” says Richter. “It’s a film I owe a lot to, it taught me the power of matching incredible images with incredible pieces of music. Kubrick knew that if there wasn’t a piece of music that could match the pure spectacle on the screen then it was best to leave things silent, which is probably why so much of 2001 is in silence and based around the white noise of space. I learned a lot from that. If silence is more powerful or symbolic, then your job as a composer is to exercise some restraint.”

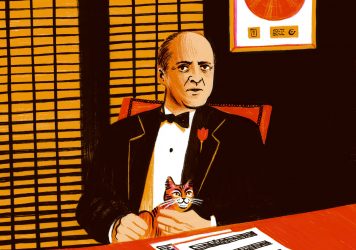

Richter is regarded as one of Britain’s greatest living composers, with his records ‘Memoryhouse’ and ‘Infra’ among the standout achievements of contemporary classical music. He’s also contributed original scores to the theatre, ballet and film. His work is grounded in raw emotion and other worldly mystique, blending electronic and classical seamlessly together.

Whether it’s working with neuroscientists to ensure his eight-hour magnum opus, ‘Sleep’, would allow listeners to actually doze off, or the mournful lament of ‘The Blue Notebooks’, which channels the avoidable pain of the war in the Middle East, Richter’s cerebral pieces are filled with hidden meaning – something he learned directly from Kubrick’s classical choices. “The film is about asking these big philosophical and scientific questions,” Richter says, “and it’s clear Kubrick wanted to pick songs that reflected their enormity. The opening, with Richard Strauss’ ‘Also sprach Zarathrustra’, with its direct echoes of Nietzsche and the idea of the human species transitioning from the animal world to the next evolutionary leap by becoming the Ubermensch, sets up the whole psychodrama of the film in such a unique way. From Strauss to György Ligeti [the film] runs the full gauntlet of the human experience.”

Kubrick had originally commissioned British composer Alex North to score 2001, but felt his work was too obviously trying to tap into the conventions of the sci-fi genre. So the director ended up licensing the “guide pieces” he had chosen in the editing suite instead. The legend goes that North didn’t find out that his music had been scrapped until he was sitting in the audience at the film’s premiere. Although this method was “clearly horrible”, according to Richter, Kubrick’s decision was ultimately “fully vindicated”.

“The music and the imagery in 2001 represents everything that’s great about human endeavour and ingenuity.”

Richter particularly admires Kubrick’s decision to use Ligeti’s discordant and experimental ‘Requiem’ in the film’s ‘Stargate’ sequence, where astronaut Dr Bowman (Keir Dullea) is pulled into a vortex of contrasting colours that sit somewhere between blissful acid trip and nightmarish assault on the senses. As this surreal scene unfolds, the dread-inducing music sounds like death rattles filtering through the wind, as the music slowly transitions from twisted hell-scape into strangely soothing equanimity.

“Using Ligeti in that scene was such a bold choice,” he says. “Remember, this was very experimental classical music that was only a few years old [when 2001 was made] and confused just as many people as it enthralled. Ligeti’s music hits you in such a direct way. His music is so sophisticated in its construction. It is a myriad of interlocking lines moving through these sonic masses, but it really works with the film’s bold, abstract imagery. The fact that Kubrick even thought to combine them says a lot about his genius.”

Richter provided the score for director James Gray’s 2019 sci-fi Ad Astra, which follows Brad Pitt’s depressed astronaut as he moves through the solar system in pursuit of his father. The plot quite obviously mirrors the journey taken in 2001, and the construction of the film’s score spoke profoundly to Richter’s admiration for Kubrick’s meaningful song choices. Arguably, Richter went even deeper.

“A lot of the electronic music in Ad Astra was made with old mood synths from the late ’60s so we could directly channel the spirit of Ligeti’s work in 2001. It’s both an inward-looking story and also this big space epic, so I knew I had to tow the line between punchy sounds and these tender, introspective moments, where the music has to symbolise and elevate all that isolation Brad is feeling. I knew I wanted to do something really different, too.”

He explains further: “I came across the Voyager probes, which have been sending back data every nine seconds while travelling through our solar system since the mid ’70s. We actually got our hands on their raw data. We took the plasma wave radiation readings of their flybys of all the planets and created computer model insolence from this data. It means I could transform the data into actual sounds and then play their sounds like actual instrumentation. When Brad flies past Saturn or Neptune, you are actually hearing material gathered from the Voyager satellite probes from those planets. The soundtrack is quite literally embedded in space.”

This unique approach looks to have been extended to Richter’s upcoming new studio album, ‘Voices’, which he says evokes the spirit of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. “It is a project that is about the societal changes we have been going through over the last few years, and what we might have lost. I want the music to remind us of some of the good stuff that we have achieved as a species, which is why the piece is centred on the UN declaration of Human rights. It’s quite amazing that you had this thing drafted by thinkers and philosophers directly after the disaster of World War Two. It isn’t a perfect document, but I believe it points the way.”

Even though it sometimes feels like the world as we know it is falling apart, Richter seems fairly optimistic about the future. Switching back to the subject of 2001, Richter is keen to stress that the film shares the hope that he feels, arguing that it’s less rooted in darkness and emotional dissonance than its reputation suggests. “Remember that the gorgeous ‘Blue Danube Waltz’ lights up an interlude that features spaceships which appear to dance in rhythm to the music. There’s an incredible playfulness to that sequence and Kubrick’s choice of music. It’s very balletic. The music and the imagery represents everything that’s great about human endeavour and ingenuity, but also joy, too.

“There are touches of humanity like this all over the film,” Richter concludes. “The ending is full of potential and channels the spirit of optimism and modernism in the 1960s. It fights against this idea that technology will be our downfalls and suggests humans can fix their own problems. This is an idea that speaks deeply to where we find ourselves today. It suggests that we can change things for the better, and that there’s a light on the horizon.”

Published 22 Jul 2020

By Thomas Hobbs

The Midsommar composer, better known as The Haxan Cloak, reveals how he drew inspiration from Jerry Goldsmith’s classic soundtrack.

By Adam Scovell

Visiting the southeast London estate featured in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film makes for a dystopian experience.

By Thomas Hobbs

The composer and Cat’s Eyes member discusses her deep connection to Nino Rota’s 1972 masterpiece.