Reptilian newsreader Howard Handupme looks to camera: “A meteor, three times the size of Earth, is heading towards us in a collision course that will result in the extinction of all life on this planet.”

Left of frame, a rubbery green hand slides a sheet of paper across the desk. “This just in,” Handupme reports. “No, it’s not.”

“Oh, good,” says Earl Sinclair – a simple, workaday Megalosaurus – who promptly changes the channel.

So opens the first episode of the irreverent sitcom Dinosaurs, in which the dysfunctional Sinclair family contends with the strictures of modern life (dinos, in this timeline, having only evolved from being wild, swamp-dwelling brutes about a million years earlier).

A Jim Henson Television production, the series starred a cast of expressive – and expensive – animatronic puppets, the most memorable being Baby Sinclair (performed by Kevin Clash, who also popularised Elmo). Back in the show’s original run from 1991-94, Baby’s wily slapstick and weekly catchcry ‘Not the Mama!’ eclipsed the show’s more subversive quirks. But in the 30 years since Dinosaurs’ debut, its biting satire and sly commentary on gender, labour, politics, racism, the economy and climate change – not to mention television itself – has only grown more savage.

With its four idiosyncratic seasons hitting Disney+ on 29 January, now is the perfect time to reconsider this curious analogue artefact. From its prehistoric Pangaea setting (roughly 60 million years BC through to its reflection in the Anthropocene, withering under late capitalism, the prophecy of Dinosaurs is anything but obsolete.

Dinosaurs charged onto the US network ABC (plus ITV and Disney Channel in the UK, among other territories) care of co-creators Bob Young and Michael Jacobs. Their previous writing and producing credits included such all-American candy floss as The Facts of Life and Charles in Charge, but this new beast sacrificed the sweet accessibility of cookie-cutter sitcoms, favouring the playful parody and contained chaos vital to much of Jim Henson’s work, particularly with the Muppets.

That said, Dinosaurs was the first major Jim Henson Company work produced without supervision from the Creature Shop’s founding leader, who passed away in May 1990. Henson is said to have conceived the series, which shares thematic DNA with his unproduced screenplay for The Natural History Project – a fantasy feature à la The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. Sadly it was scrapped due to its apparent similarities to The Land Before Time, at a time when Jurassic antics were just starting to peak on the pop cultural landscape.

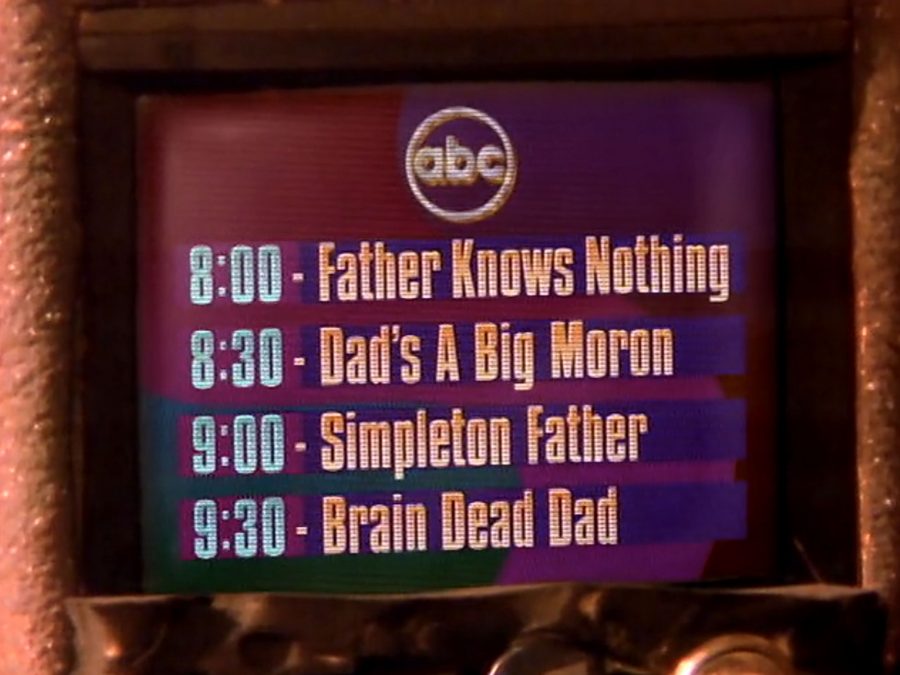

Another way in which Dinosaurs tapped the early ’90s zeitgeist was by gutting the ‘wholesome ’50s father’ archetype. Upstanding dads had dominated sitcoms (subgenus: comedie domesticus, or ‘dom coms’) from Father Knows Best to The Cosby Show. Full of beer nuts and hot air, Earl (voiced by Stuart Pankin) inherited the ‘bad dad’ mantle from Alf Garnett (Till Death Us Do Part) and Archie Bunker (All in the Family), whose parenting deficits were honoured such ‘dumb dad’ renaissance texts as Married… with Children, The Simpsons and Home Improvement. Dinosaurs even skewered the trend with this facetious weeknight line-up:

“This is why TV stinks,” groans Earl. “One show’s a hit, they make 50 more like it,” to which Baby replies, “Don’t have a cow, man!”

But Earl is more cynical than his bumbling brethren like Homer Simpson and Fred Flintstone. What’s more, his wilfully shit behaviour isn’t typically framed as endearing, so we don’t laugh with him – the chuckles come when he gets his comeuppance. (Notably, Dinosaurs’ producers chose to can the initial laugh track, which means no one implicitly condones Earl’s buffoonery.)

Unlike many TV patriarchs, Earl is rarely handed a free pass to fail upwards, which makes it all the more meaningful when, in the third season episode ‘Honey, I Miss the Kids’, the flaccid antihero sincerely bonds with his progeny. Meanwhile, his wife Fran (Arrested Development’s Jessica Walter) returns to work full time, itching to escape the cyclical tedium of domestic drudge work.

A prototypical nuclear family, the Sinclairs live in a version of suburbia that marries prehistoric aesthetics and postwar social values. Every relevant stereotype gets eviscerated, along with the idealised virtues of heteronormative parenthood (both adults express resentment toward each other and their kids), organised religion (teenage son Robbie rejects many cultural customs, like eating other animals and hurling old folk into tarpits), and soulless consumerism (when Baby demands the ‘leg smoother’ he saw on TV, he’s told he can’t have it because he’s a boy. “Oh, then I want a machine gun!”).

Traditional gender roles receive constant ribbing, with clichéd traits inverted. Man of the house Earl is beholden to the whims of his – to borrow a Sesame Street term – big feelings, whereas Fran is mostly moderate. Though she begins an obliging housewife, one part Stepford to two parts Bedrock, she becomes disillusioned with her lot and develops the voice to say so.

This is largely due the influence of her friend Monica Devertebrae (Suzie Plakson), a feminist Brontosaurus who takes her employer – the ubiquitous corporate giant WESAYSO – to court in ‘What “Sexual Harris” Meant’. The episode aired in late 1991, just two months after Anita Hill’s widely televised sexual harassment case, and it features one of Dinosaurs’ most searing jokes.

The ignobility of work regularly comes under fire, particularly in regard to Earl’s blue-collar job as a ‘tree pusher’ at WESAYSO Development Corporation. Managed by a tyrannical Styracosaurus called BP Richfield (sitcom stalwart Sherman Hemsley, All in the Family and The Jeffersons) who’s slick by name, if not by nature.

The company motto is “We’ll do what’s right if you leave us alone”, which, in practice, means razing a redwood forest to make way for 10,000 tract houses, and building a wax fruit factory that precipitates an ice age. (Howard Handupme’s news report was right: it’s not a meteor that ends all life on Earth in the series’ breathtakingly bleak finale.)

Dinosaurs leaves few sociopolitical stones unturned, illustrating how gender performance, class, work and the environment are all inextricably linked. In some ways, it’s a spiritual successor to another Henson series about ecology, Fraggle Rock, which also depicts nature’s precariousness and the dangers of xenophobia. (Earl’s opinions of the early hominid folk who cohabit this revisionist history echo the Fraggles’ view of ‘Silly Creatures’ aka the human race.) This begs the question, was Dinosaurs intended for adults or children? Like most Jim Henson Company work, it’s both, and the writers clarify this with a knowing wink.

The Sinclairs’ television set is their home’s focal point, and some of the show’s best roasts concern TV’s hypnotic allure. (‘Network Genius’ is a work of genius.) But Dinosaurs’ drollest running gag involves a puppet show that delights Earl and Baby equally. When Fran dismisses the show as kid’s stuff, Earl retorts, “You’d think that, because they’re puppets – so the show seems to have a children’s aesthetic.” He turns to eyeball the camera. “Yet the dialogue is unquestionably sharp-edged, witty, and thematically skewed to adults.” The mighty Megalosaurus flexes his dexterous brow.

Puppets mimic the human condition with an uncanny likeness. They’re not people, clearly, but an eerie approximation. When camouflaged in the soft power of a sitcom, they have a unique capacity to point fingers at society’s trickiest home truths. Slapstick and catchphrases are just a handy distraction. All these years later, Dinosaurs still goes for the throat.

Published 28 Jan 2021

By Aimee Knight

The birth of the Muppet Cinematic Universe remains a high water mark for family moviemaking.

By Taryn McCabe

So much about this cult fantasy endures, from its use of practical effects to David Bowie’s captivating performance.

Tale of Tales is a return to a much darker, more traditional form of fantasy storytelling.