Paul Newman always preferred the journey to the destination. Explaining the difference between his acting approach with his wife, Joanne Woodward’s, he said, “Joanne enjoys acting, I don’t. I enjoy the rehearsing, the intellectual exercise.” Even as one of the last great movie stars, Newman was always happiest behind the scenes and built a successful adjacent career as a producer and director. Similar to his approach to acting, as a director, he emphasised performance and reflected the intimate structure of improvisational spaces.

In 1968, Newman directed his first feature, Rachel, Rachel, starring Joanne Woodward. An adaptation of Margaret Laurence’s novel ‘A Jest of God’, the film follows a middle-aged school teacher who experiences a late coming of age. Rachel’s interior world dominates the direction of the film, as her dreams, memories and fantasies guide the narrative. Rather than a film about big events, it is about the accumulation of small incidents that lead to a transformative shift.

In Rachel’s world, small talk or a morning alarm can set off a range of thoughts and ideas. While the film relies heavily on an interior monologue as a form of narration, its abstract premise focused on the interior world of the character is difficult to translate for both actor and director. Tasked with evoking a more mature coming of age, Woodward counterbalances a jaded knowingness with a stunted personal evolution by articulating the difference between intention and impact. As Rachel’s desires are articulated for the first time in the real world, she’s presented with disappointment and ecstasy in equal measure.

For his second directorial effort, 1971’s Sometimes a Great Notion, Newman took over shooting several weeks into production. Based on a novel by Ken Kesey, the film tells of a family of timber cutters defying a local union by continuing to work during a strike. Newman stars along Henry Fonda, Richard Jaeckel and Lee Remick.

Much of the film is focused on the work and leisure of the characters without great incident. Numerous extended sequences take place around the breakfast table as characters make off-colour jokes and drink. Striking a loose, naturalistic tone, the film has a relaxed pacing and almost mundane atmosphere. This builds up to an incredible climactic sequence as a rotten tree collapses, injuring two characters. Ignoring the easy signifiers for panic and pain, the character reactions build on the ordinariness that preceded it to achieve a scene of incredible poignancy and unexpected depth of emotion.

A year later, the extravagantly titled The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds reunited Newman with Woodward. As in Rachel, Rachel, she portrays a character who is frowned upon by the rest of society: an older unemployed woman caring for her two daughters. Nicknamed the “loon”, Beatrice is a loud-mouthed jokester. Constantly grifting and hustling to afford to continue to care for her children, she is repeatedly humiliated over the running of the film.

While not quite as accomplished as Newman’s earlier efforts, this is nonetheless a prime example of a director obsessed with process and performance. Woodward plays things “ugly” in service of the reality of a well-meaning character whose abrasiveness makes her a social pariah. Many of her scenes feel like acting exercises more so than final products, as she utilises performance as a mean of underplaying her character’s vulnerability. Often playing with props or costume, Beatrice tries to escape from her boring reality through performance itself by adopting a variety of personas.

Newman’s next film was The Shadow Box, a made-for-TV adaptation of Michael Cristofer’s Tony Award-winning play about three terminally-ill patients. With a more restrictive budget and locations, the film sometimes feel a bit like canned theatre, limiting its overall impact. Yet the performances all round are remarkably strong – particularly from Woodward and Christopher Plummer – once again underlining Newman’s preference for actors who are able to move beyond the classical emotional markers for sadness and grief in order to achieve a greater sense of truth.

Newman’s next film, 1984’s Harry & Son, is more contentious; its reportedly troubled production is often reflected on screen. While Newman nonetheless gives a great performance, his co-star Robby Benson lacks the same energy and emotional power. The screenplay by Newman and Ronald Buck is unfocused, though the film is still interesting in the way it reflects on masculinity, work and identity.

Arriving three years later, Newman’s last film behind the camera, The Glass Menagerie, stars Woodward and a fresh-faced John Malkovich. The extended rehearsal process was documented in screenwriter Stewart Stern’s biography ‘No Tricks in my Pocket: Paul Newman Directs’. In the book Newman reveals the limits he set upon himself and describes his hand’s off approach on set, directing the action only if the actors’ asked.

Rather than try to abstract Tennessee Williams’ famous play, using voiceover narration and multiple location changes, Newman wanted to show how it was portrayed on stage, transplanting a live audience for a camera. He hoped that the limits of cinema, rather than feel restrictive, would accentuate the claustrophobic aspect of the play. For various reasons ‘The Glass Menagerie’ is not compatible with conventional narrative filmmaking. Newman’s adaptation is ultimately uneven, but it does have a certain minimalist beauty, and faithfully adheres to Williams’ single location setting.

While his films were often made through traditional means with an emphasis on naturalism, Newman now seems ahead of his time in his inherent understanding that the destination is not always the essential part of the filmmaking process. Exceptionally in the Hollywood arena, his directorial personality is product adverse as he is taken in by the journey of making a film rather than its end result.

Published 26 Jan 2019

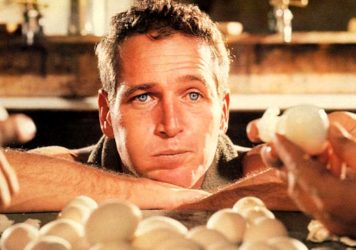

The late Hollywood iconic lets his physical attributes do the talking in this classic prison drama.

By Elena Lazic

From the Sundance Kid to Jay Gatsby, here are some of the Hollywood icon’s most memorable characters.

With The Childhood of a Leader arriving in cinemas, here are some other memorable shifts from stars behind the lens.