A lineage of unexpectedly popular supporting characters transformed, even resurrected, across works by their makers to become leads of their own stories can be traced from Sir John Falstaff via Frasier Crane and now Pat Tate (Craig Fairbrass), star of the spiritedly nasty and weirdly jolly Rise of the Footsoldier films, the latest of which arrived on VOD last week.

What began in 2007 as a straightforwardly brutal Brit gangster film with Rise of the Footsoldier, a grimy epic built around the various hooligans, club promoters and drug dealers involved in the real life Rettendon Range Rover murders, has by 2019’s entry, Rise of the Footsoldier: Marbella, transformed into something more akin to comedy, and certainly removed from any claims to historical verisimilitude.

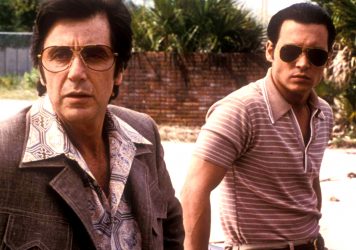

The new film is a violent cartoon in which a supporting character and fan favourite from the first film, brutish gangster Pat Tate (Craig Fairbrass), is now firmly the lead of the saga: breaking heads, cussing out jokers, double crossing low-lifes in the Spanish sunshine and the mean streets of Essex and generally kicking off. All this plays out against the backdrop of an ’80s and ’90s setting mostly defined by the strategic deployment of a few catchy era-appropriate tunes over any extravagant or expensive period detail beyond tracksuits, cheesy shirts and bad haircuts worn by the central cast of hoodlums.

Rise of the Footsoldier is, of course, just one of many cheap and cheerful films taking the Rettendon shootings as inspiration for various Essex Boys-themed gangster frolics. The likes of Essex Boys, Bonded by Blood, Fall of the Essex Boys, Essex Boys: Retribution, Essex Boys: The Laws of Survival and Bonded by Blood 2 all deliver violent antics with varying degrees of seriousness, often deploying the same actors and crews. These British films also neatly traverse the years which separate the theatrical break out hits of the likes of Guy Ritchie, Matthew Vaughn and Nick Love in the early 2000s from the current market for cheerfully unpleasant, apparently rather anonymous straight-to-video UK mob flicks.

Even the eight years that separated the original Footsoldier from its first sequel, 2015’s Rise of the Footsoldier Part II, saw the franchise adjust budget and scale, situating itself firmly in home video territory. This is in no small part due to a more general industrial shift of the British gangster/hooligan genre into that space due to volume of output as much as audience appetite for cheap and sleazy home entertainment. Inevitable parodies, notably Nick Nevern’s The Hooligan Factory from 2014, reflect a genre at absolute saturation point. But it is not simply the market that dictated the change in form and style for the Footsoldier sequels.

While the second film continues in grimly morose mode, expanding on the story of lead Carlton Leach (Ricci Harnett, who also wrote and directed the film) and dealing with the aftermath of the shootings, there is some hint of the direction the franchise would later go, particularly in more leisurely paced dialogue scenes that give full flavour to the series’ now characteristically frequent and inventive swearing. Slang and insults are hurled between low-rent gangsters during brawls and torture scenes with merry abandon, while the visual style is also less erratic and showy than in the first film, though an obsession with displaying the naked female form in languorous montages, as well as the kinetic and frantically edited fights, remain intact.

However, by the third Footsoldier, a new narrative and tone are firmly established, attributable almost entirely to Fairbrass’ Pat. Dead by the end of the first film, Tate is resurrected to appear in nominal ‘prequels’ which essentially transform the series into a vehicle for the character and his closest criminal associates (played with gusto by Terry Stone and Roland Manookian) to riff off each other with energetically juicy dialogue in between sessions of often niftily choreographed violence, sex and drug taking.

Rise of the Footsoldier 3 and Marbella combine elements of prison drama, classical rags-to-riches gangster movie, British crime caper and even ’70s sex comedy to deliver infectiously entertaining, generically slippery low-budget fun. Their slim budgets and loyal fanbase allow for a playfulness and stretching of narrative and general logic, such that it would be little surprise should the same characters visit the moon or fight zombies in a future outing.

The elements hang together loosely by inventively profane dialogue (“When a stone-cold fucking cokehead refuses a fat line of gear, you don’t need to be Miss Cunting Fucking Marple to realise there’s something fucking seriously wrong!”) and, crucially, the good humoured appeal of Fairbrass’ performance. A lumbering, intimidating figure, Fairbrass exudes power and menace on screen. But the tone of the latest films is so emphatically hysterical, so insistently extreme, as to never be taken too seriously; the brutality never really felt beyond a puerile glee at the transgressive excess on screen. Fairbrass, meanwhile, has edged further into subtle self-satire in a way that matches the franchise’s newly invigorated parodic energy.

Tate, a real-life Essex boy, appears in the original film as a far more overtly malevolent figure, capable of sudden, horrific violence as the ringleader of the doomed crime ring executed at Rettendon. The historical accuracy of the film and Fairbrass’ depiction of Tate is the subject of heated debate. But it is safe to say that by the time of his reappearance in the third and fourth films he has morphed into something entirely separate and comedic – a sly send-up of the UK gangster hard man, played convincingly straight enough for the character to remain menacing, yet somehow perversely endearing.

Published 13 Nov 2019

By David Hayles

In 1947’s Kiss of Death, Richard Widmark plays a murderous Joker-styled sociopath.

Johnny Depp is on career-best form in Mike Newell’s classic crime-thriller from 1997.

Before Mike Hodges and Michael Caine, there was Masoud Kimiai and Behrouz Vossoughi.