Like a living body, Candyman is composed of miraculous parts, each working in perfect harmony: original source material by horror master Clive Barker, photography by Nicolas Roeg’s regular DoP, a hypnotic Phillip Glass score, Jacques Tourneur-level direction from Bernard Rose, and a luminous lead performance from Virginia Madsen. With the exception of the music, all of this is missing from the 1995 sequel, Candyman 2: Farewell to the Flesh. And yet somehow, the film retains a lick of the original fire.

We’re in the directorial hands of Bill Condon, a skilled visual storyteller. Kelly Rowan is a passable Madsen substitute, and horror legend Veronica Cartwright plays an edgy Southern matriarch. Crucially, Tony Todd returns as the titular killer, and with a hook hand and a delicious coo, slices his victims “from gullet to groin”. But the film can’t be reduced to this checklist. Farewell to the Flesh elicits a similar state of woozy imbalance as the original because both possess the same strange, irreducible qualities: a dream logic of mirror portals and bee-infested torsos, history wrenching itself into the present, generic oscillations between ghost story and slasher, and an insistence on asking difficult questions about American racism.

The story centres on Annie, an art teacher whose father was murdered while researching a series of brutal killings. When Annie summons Candyman to soothe the fears of her students, the skewering begins. As she learns about the killer’s life and investigates her own family history, Annie discovers that the two intersect in shocking ways. The film leans into its ghost tropes over slasher conventions, prioritising the tangle of dark family secrets over imaginative death set-pieces. Like the best supernatural tales – The Changeling, for example – family lore reveals the traumas of national history; Annie’s ancestral relationship to Candyman, a plantation slave, points to the racism at America’s foundation.

Family bonds replace romantic couples as the central relationships. Annie’s husband is dispatched early on, while the juiciest dynamics are between Annie, her golden-boy brother, and their brittle, controlling mother. An early close-up of the key to a drawer containing sepia photos signals the mother as the gatekeeper of family memory. These elements place Farewell to the Flesh in a tradition of sprawling Southern family melodramas, stretching from William Wyler and Douglas Sirk to Steel Magnolias and Fried Green Tomatoes.

The wide streets and Spanish moss-encrusted mansions of New Orleans replace Chicago’s Cabrini Green estate. The script, anxious to emphasise the Louisiana setting, references gumbo three times in the first ten minutes, and the film’s occasional narrator is a local DJ and Mardi Gras hype-man. As we progress towards a carnival denouement, the festivities create some of the most memorable images: a gnarled snowball salesman, packs of masked millenarians, and a glorious shot of Candyman, among the crowds, tiki torches flashing across his face.

Of course, the film is guilty of choosing a generic ‘ethnic’ milieu to compliment the themes of the narrative, without any heed to the Cajun specificities of carnival celebrations. But Mardi Gras is window dressing; two Southern mansions are the spatial core of the film. In melodramatic style, the family home is the crucible of the real action. The final scene moves from the crumbling plantation house to the wooden slave quarters, and, in a haunting prefiguration of the devastation wreaked by Hurricane Katrina a decade later, Annie and Candyman almost drown during a storm.

Farewell to the Flesh exhibits a savvy awareness of its own political limitations. In two early scenes, the blackness of young men is exploited for cheap jump scares, but the sequences function to indict the audience, forcing them to consider their own unconscious profiling. By unearthing Candyman’s slave past, the film also critiques a culture that, following the success of the first film, elevated Todd’s character to a folk villain but defanged him of his complex political meanings.

So go, bear witness to the film’s strange pleasures, fall victim to its accusations, but never – never – mention the third in the series.

Published 15 Mar 2020

By Anton Bitel

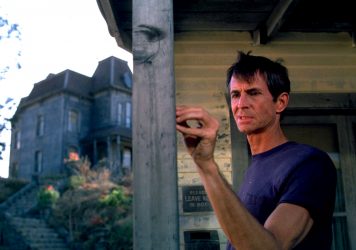

Richard Franklin’s follow-up to the Hitchcock classic is a chilling horror in its own right.

Is Joseph Sargent’s universally derided 1987 film really one of the worst sequels ever made?

By Anton Bitel

Both film are now available as part of a special collector’s edition box set.