What does the history of British Chinese film look like? Answering this question is a troubling task, because the history of British Chinese people on screen is necessarily also a history of British Sinophobia. Do you start in the 1920s, when Harry Agar Lyon’s Fu Manchu embodied the worst of Yellow Peril scaremongering? Do you celebrate the success of Burt Kwouk or Tsai Chin in the ’60s, even though their work was often littered with harmful stereotypes? While bona fide stars like Gemma Chan have emerged in the last decade, lead roles remain scarce and opportunities behind the camera even scarcer.

In this context, 1986’s Ping Pong, the first feature film by a British Chinese director, is a curious outlier. It tells the story not of a single British Chinese character but of 23, representing various backgrounds, generations and languages. At the film’s centre is Sam Wong, an ageing restaurateur who winds up dead in a Soho phone box. As the members of his family contest and compete over the terms of his will, trainee lawyer Elaine Choi (Lucy Sheen) is left to pick up the pieces as she navigates the morass of Chinatown’s fragmented community.

Ping Pong’s poignancy lies not in its willingness to define British Chineseness for a general audience but in how it expresses the elusive nature of such a definition for the diverse community it represents. Choi, for example, barely speaks a word of Cantonese, let alone Mandarin, having immigrated from Macau at the age of seven. When a Chinese embassy staffer suggests “go back to your homeland” to reconnect with her heritage, she quips, “which one?”

The film itself, by extension, defies categorisation, its knotty structure and sprawling cast allowing it to jump from neo-noir to comedy of manners in a matter of moments – director Po-Chih Leong even tosses in a fake wuxia film for good measure. The narrative unravels like an elegant puzzle: as Choi stops by each member of Wong’s family, they reveal new details about the will, each other, and eventually themselves.

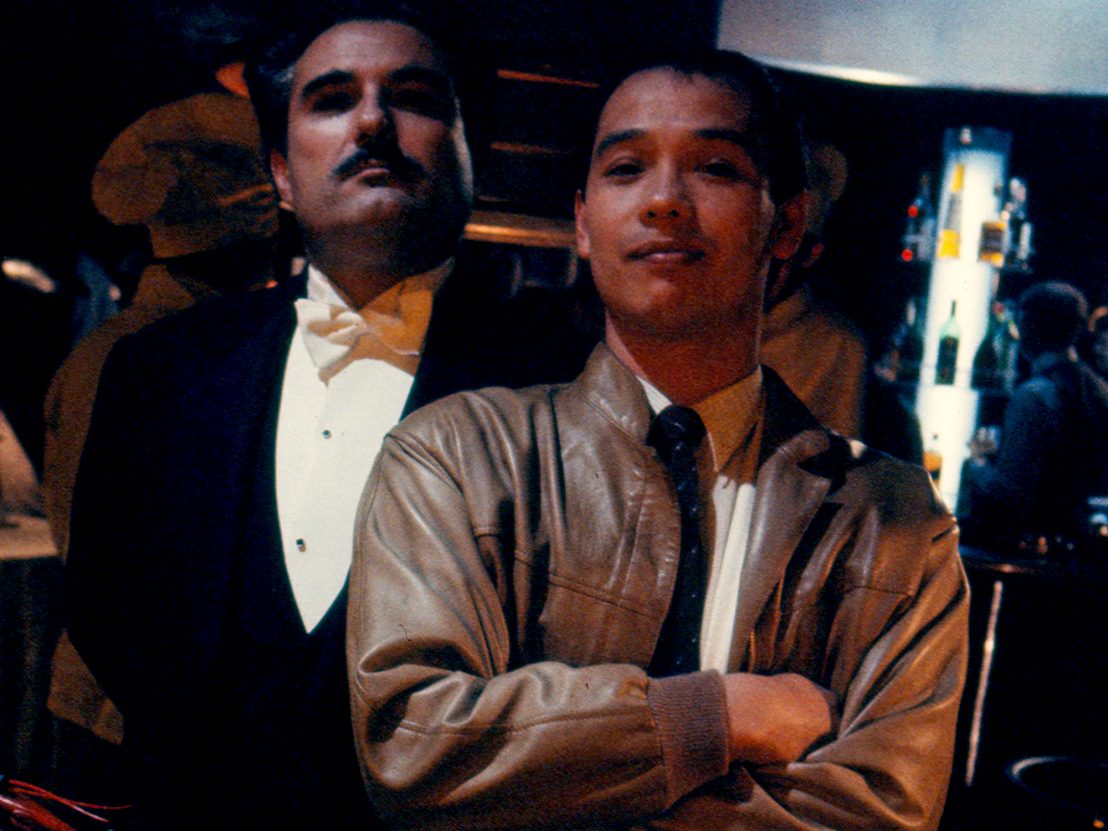

As an outsider to the Wong family, Choi serves not only as a surrogate for the audience but as a conduit for the film’s foregrounding of each characters’ neuroses. We meet Wong’s traditionalist son-in-law who quizzes his sons on the four great Chinese inventions; by contrast, Wong’s RP-accented younger son Mike (David Yip) scoffs at his father’s Chinatown business, opting instead to run an upscale Italian bar for a white clientele.

Crucially, no one is shown to be more or less Chinese than anyone else; there is none of the self-indulgent navel-gazing around identity that so often plagues immigrant storytelling. Instead, Ping Pong simply presents British Chinese life as is: gambling addicts, social climbers, undocumented immigrants and doctors are all part of the same rich, messy tapestry.

“The modest success of the ’80s, and the drought that followed, belies a simple narrative of racial progress on British screens.”

Given the numerous firsts Ping Pong represents (it was also the first film to be shot in London’s Chinatown), it would be easy to view it as a unique, unprecedented hidden gem. But this was the crest of a wave of British Chinese on-screen creativity which spanned the ’80s. Yip, for example, was already familiar to TV audiences through his role in the BBC’s short-lived police procedural The Chinese Detective. Not only did the show cast a Chinese actor in the lead – already an improvement on Charlie Chan! – it eschewed kung fu caricatures in favour of an intelligent, charismatic detective, the kind of role which almost always went to white actors.

The launch of Channel 4 in 1982 was similarly instrumental in helping to establish British Chinese talent. As well as co-funding Ping Pong, the network assisted the production of Soursweet, Mike Newell’s 1988 adaptation of British Chinese writer Timothy Mo’s novel of the same name.

Ping Pong was not an aberration, then, and it was not forgotten so much as discarded. Despite a successful run at the 1987 Venice Film Festival, it met with a lukewarm reception. Within a few years, opportunities for British Chinese actors had all but dried up. “You come to the 1990s and it all seemed to stop,” Sheen said in a 2012 panel discussion. The few British Chinese cultural figures that emerged in the interim – Katie Leung’s Cho Chang, for example – were sidelined or mocked. It wasn’t until 2015 that Ping Pong became widely available via BFI Player.

The modest success of the ’80s, and the drought that followed, belies a simple narrative of racial progress on British screens. The funding and institutional backing which gave Ping Pong a chance was just as easily denied to British Chinese filmmakers like Rosa Fong and Lab Ky Mo who struggled to garner industry support during the ’90s and ’00s.

This lesson feels all the more pertinent now that, entering the 2020s, a new wave of British Chinese talent has begun to emerge, increasingly politicised in the wake of Covid-related racism and often working in solidarity with other East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) communities. Advocacy groups like BEATS, who cite Ping Pong as a benchmark for representation, are calling out colonial apologia on TV, while directors like Hong Khaou and Xiaolu Guo are arthouse staples.

Yet the terms of this success are troubling. How many ESEA actors have had to cross the pond and take bland side roles in the MCU just to gain recognition? How many studios and investors are willing to back ESEA filmmaking which is experimental, transgressive or political? Why are there still no films documenting ESEA history, such as the deportation of Liverpool’s Chinese seamen?

Answering these questions might mean revisiting the unvarnished independence of films like Ping Pong. The film, despite its imperfections, has an inventive, subversive zeal whose potential this new generation of ESEA filmmakers is yet to fully unlock. Building a lasting ESEA film movement might mean stepping away from the trappings of commercial success and even the conventions of film itself, and instead seeking a new cinematic language which can articulate the beautiful, contradictory truths of our communities. Only when we demand this of funders, institutions, and most importantly ourselves, can we truly begin to write our own film history.

Published 11 Aug 2021

By Ian Wang

Lee Isaac Chung’s film carries on a tradition of skepticism towards the promises of cultural assimilation.

As a Desi girl coming of age in the early 2000s, Gurinder Chadha’s film has a profound impact on me.

“Chollywood’’ is set to become the next major rival to North America’s film industry.