In 1986, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, a micro-budget horror film from first-time director John McNaughton, disturbed critics and audiences so much that it challenged the paradigms for on-screen violence. Loosely based on real-life serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, whose crimes spanned 1960 to 1983 (he was convicted of the murder of 11 people but confessed to hundreds more), the film debuted at the Chicago International Film Festival and gained infamy on the festival circuit where it was championed by Roger Ebert.

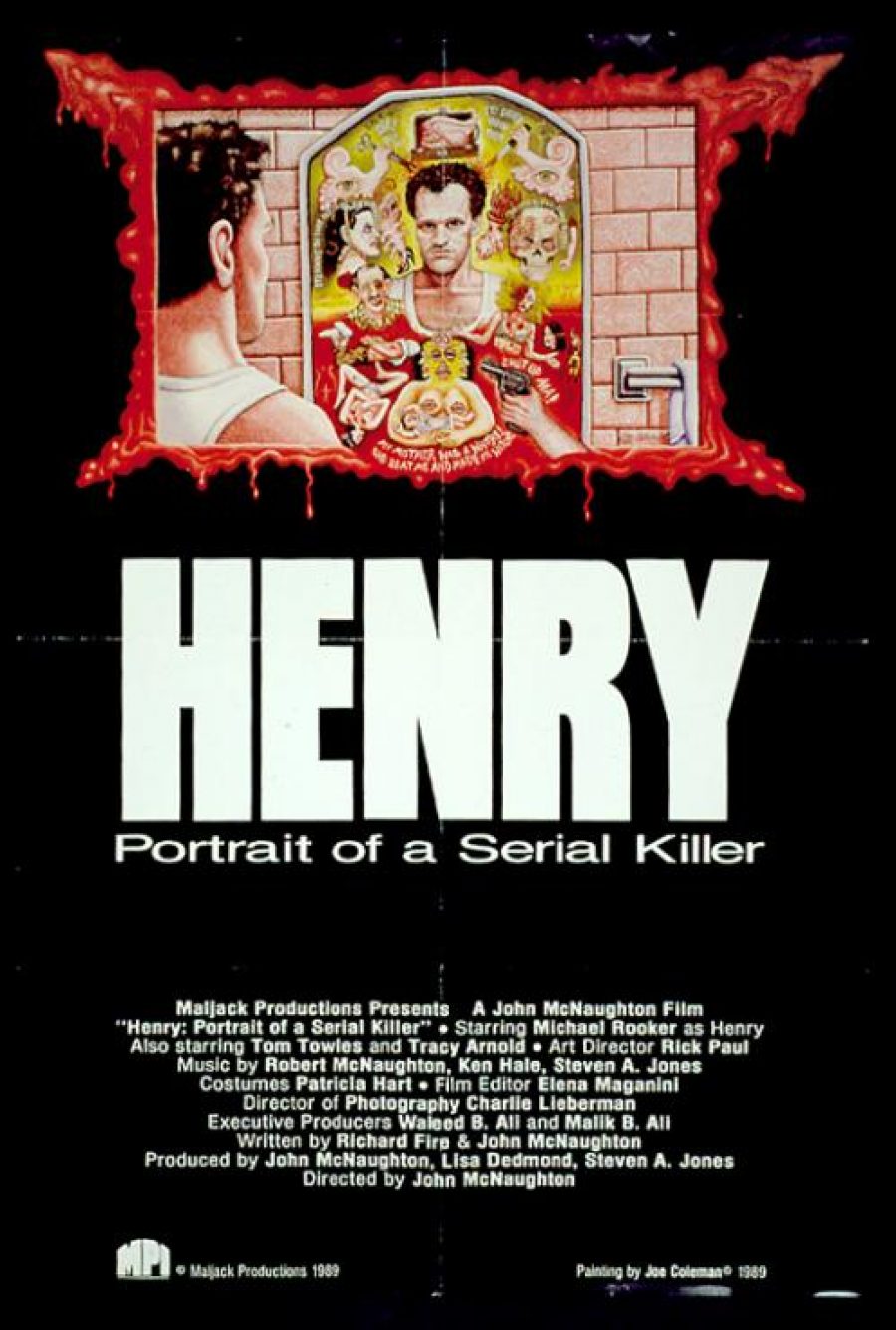

The Motion Picture Association classified Henry with an ‘X’ rating, normally reserved for pornographic films. They advised McNaughton the rating would not change no matter what edits were made. Even its poster, by outsider artist Joe Coleman, was deemed too disturbing and outré, and was promptly withdrawn.

Alongside Pedro Almodóvar’s erotic farce Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! and Peter Greenaway’s grotesque gastro-satire The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, Henry was responsible for the creation of the NC-17 rating. It eventually received a theatrical release in North America in January 1990.

In the UK, the road to release was even more protracted and drawn out. After insisting on a series of edits to remove images of a dead woman with a broken bottle embedded in her face, and another woman being groped as she is murdered, the BBFC agreed to release the film as an ‘18’ in 1992, but then in 1993 they requested the removal of two additional murder scenes.

It was not until 2003 that the film was available in the UK in its uncut form. All this worrying about the fragile sensibilities of the British public eventually served to frame Henry as being emblematic of a moral panic at the centre of society, and the BBFC’s finicky excisions served the adverse effect of turning the film into a cause célèbre. It even became a mainstay discussion point of Media Studies classrooms across the country.

Watching it now, it’s hard to see the justification for such outrage from the state authorities. The violence and gore onscreen is not particularly gratuitous; milder than any of the films in the Saw franchise and many episodes of serialised prestige television such as Game of Thrones, Hannibal or American Horror Story. But while those shows can shield the viewer from violence with veils of fantasy, style or camp, there is something in Henry that is inescapably bone-chilling.

The film’s title is misleading as it evokes the kind of artistic gentleman killer that Anthony Hopkins would win an Oscar for in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs. This is a film with a comparable level of violence and murder to Henry, and to which the BBFC had no objection, having since downgraded its classification from ‘18’ to ‘15’. It begs the question, why are we more accepting of violence when it is committed by an ingenious criminal mastermind than a mundane everyman?

Henry (Michael Rooker) is barely literate and has none of the style, intelligence or integrity of Lecter. He is a paragon of purposeless, mundane evil. As Lecter delights in his recollections of murdering a man and eating his liver with fava beans and a nice Chianti, Henry cannot remember whether he shot or stabbed his mother. His modus operandi is simple; change your weapons, change your method of disposing of the body and don’t stay in any one place for too long. With that alone Henry is able to continue on as an apex predator with an unquenchable thirst for misery.

Unlike The Silence of the Lambs, Henry does not have a typical narrative: there is no investigation; no vengeance in the works; no prison to escape from. Instead it tells the story of the outwardly unremarkable Henry over a few weeks, as he stays with his friend Otis (Tom Towles) and his sister Becky (Tracy Arnold), and calmly goes about his business of murder. There’s not even a particular pattern that he follows: sometimes he kills out of anger; sometimes out of a dispassionate, obscure compulsion to do so.

He tentatively begins a relationship with the sweet and oblivious Becky but there is no true redemption to be had. Otis and Becky also have real-life counterparts in murderer and arsonist Ottis Toole, who was convicted of six murders but, like Henry Lee Lucas, confessed to hundreds more. Becky is based on Ottis’ 12-year-old niece Frieda “Becky” Powell but casting a child in this role was a step too far even for this film.

The story opens on the aftermath of the violence – the camera slowly glides over mutilated corpses as the agonised screams of a victim play out on the soundtrack. In contrast, Henry is un-phased — almost childlike in his comportment. Otis is comparatively grotesque, with rotting oversized teeth and a penchant for molesting teenage boys, corpses and his own sister.

Otis is pure id, his gleeful violence stemming from the same place as his insatiable sexual dysfunction. He is a more familiar genre presence and would have not been out of place sat at the dinner table in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Henry, on the other hand, is an unfeeling, cold-eyed psychopath, taking no joy in the tangled mass of decomposing limbs he leaves in his wake. Rooker, with a storied career as a character actor and a devoted genre following is probably best known for his scene-stealing turn as perma-screaming alien mercenary Yondu in the Guardians of the Galaxy films.

Even with the hindsight of his acting prowess and range, that this performance was his debut is miraculous. He is at once subtle and intensely physical, playing Henry with an understated menace and accomplishing an almost metaphysical impossibility of conveying a void. The scene where Becky tells him that she loves him is among the most terrifying. Rooker’s skin grows taut across his bones and eyes recess into dark sockets as he replies, slow and unblinking, “I guess I love you too,” before another unspeakable act.

The film reaches its apex (or nadir, depending on whether or not you work for the BBFC) in its infamous videotape scene. Henry and Otis, having recently acquired a camcorder and a colour television, record themselves massacring an entire family and later watch back the results. The entire sequence is shown with uncut blunt force realism via their television set. The scene, that the BBFC cut down to a fleeting few seconds, is the film at its most powerful and uncompromising. By framing this intense brutality through a television set, the film confronts us, the audience, with our motives for watching.

For all of the cannibalism, severed heads and skin suits in The Silence of the Lambs, nothing in it penetrates your skin quite like these screams for mercy and snapping of necks. There is no flair or stylisation to shield you from the bleak reality of a sadistic home invasion. While much horror trivialises murder this scene unflinchingly confronts it. Our role as voyeurs of violence and sexual assault is made explicit and uncomfortable. It establishes Henry as both an exceptional entry to the horror canon and a chilling commentary on it.

Although this film’s use of violence can be contextualised, its infamy is deserved. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer doesn’t seek to entertain so much as delve into the depths of human depravity. In portraying this man, unadorned, unemotional, cold and callous, the violence on screen retains a brutal purity that shocks and repulses. What the critics and censors saw in 1986 is the rare power of raw sadism on screen, made all the more terrifying by its mundane familiarity.

Published 31 Oct 2020

By Anton Bitel

A troubled man cracks under immense pressure in the director’s cult 1976 thriller.

Netflix’s newest crime drama series is the culmination of a career-long obsession for the director.

Jonathan Demme’s 1991 masterpiece evokes fear by putting us in the protagonist’s shoes.