“I met this six-year-old child, with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and the blackest eyes. I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up, because I realised what was living behind that boy’s eyes was pure and simply evil.”

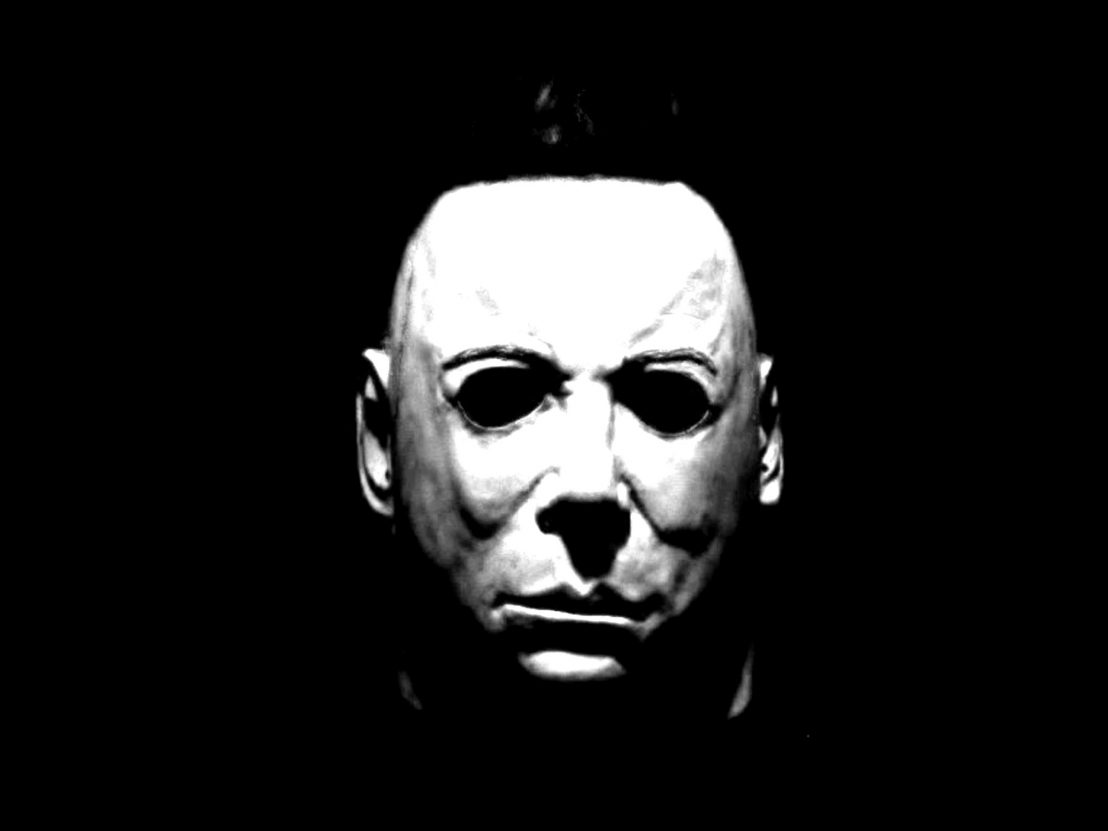

These are the words of Sam Loomis, and the child he’s referring to is no longer a child at this point in his life. He’s grown into the boiler suit-clad killer whose knife appears on the poster for John Carpenter’s 1978 classic, Halloween. Michael Myers is the earliest incarnation of what is now one of the most common stock characters in horror. One that can’t be killed, can’t be stopped, and exists for one purpose – to kill. It rarely seems to matter who the victims are, as long as they live in a place that has some relation to the killer, but the clearest trait linking those characters is the fact that they’ve been dehumanised.

During his college days Carpenter visited a mental institution. “It was very depressing. Seeing a guy, who just looked like the Devil. He was just mentally ill, but that’s what he looked like,” he has said of the experience. “That idea of evil, that’s where it came from. He’s not really, but it appeared that way. The mentally ill are not evil. They’re just sad.”

The similarities between Carpenter’s own words and Loomis’ are obvious, but there is one crucial omission from the fictionalised version – there is no sense of empathy. In fact, in the film mental illness is presented unambiguously as the reason Myers kills. And he’s not the only one – Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees, Wolf Creek’s Mick Taylor and more recent horror antagonists such as Hereditary’s Charlie all fall into this category.

The regularity with which Myers has appeared on our screens down the years is testament to his effectiveness as a boogeyman figure. Aside from the oddity that is 1983’s Season of the Witch, the character has featured in every addition to the Halloween franchise, typically operating in the same mode. He moves slowly, yet somehow manages to relentlessly keep up with his victims, and he always carries a large sharp kitchen knife. He has no discernible emotional state to speak of, which is true of every character subsequently inspired by him.

When a director wants to show a character’s mental illness, they usually portray them as quiet or mute, socially withdrawn or else showing a complete lack of interest in others. This says a lot, of course, not only about a film’s creator but society as a whole – mental illness is still viewed as something inherently wrong or threatening. In many horror films, mental illness is defined as introspective by nature, and deeply private. It can never be fully explained (or rather, won’t be by the person suffering from it) and thus it is impossible to fully understand it. Directors understand this, and very often use it to a less than altruistic end.

One of the things I ask myself whenever I watch a slasher film is, ‘What makes this antagonist scary?’ And the answer is always the same: their unpredictability. This unpredictability stems from the influence of films like Halloween, where mentally ill people are ‘othered’, forcibly separated from what most people consider everyday life. When that separation is diminished, the horror starts. It’s a concept which seems to connect with audiences, and it says a lot about how mental illness is viewed on a cultural level.

It’s a trend we can see in the latest incarnation of the Halloween saga. There’s a scene in the trailer where a group of patients are chained to the ground, at a safe distance apart, and sitting or standing at odd angles: some are crouching, others are contorting their backs in strange ways. They’re presented as taking a perverse glee in someone brandishing Myers’ mask. Here the audience is being told that these people see something of themselves in Myers, and they’re just as threatening as him.

It’s another instance of mental illness being used as a fear tactic, much like it was in Carpenter’s original and so many of the films it has inspired. It’s a tired trope, one that appears to be going nowhere in horror but which the world at large could do without.

Published 12 Oct 2018

Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead are films of hunger and the frustration of bodies.

With a pinch of Hammer Horror and a dollop of ’80s gore, this meta horror is the boldest in the series.

By Bryan Hempel

This cult classic tackles issues which have become of increasing importance since its release in 1988.