The way we write about people who have undergone gender transition needs to change. For some people, the prefix ‘trans’ is an essential part of their identity, and something they are confident to use. However, this article seeks to remind the reader that a large number of people who have transitioned simply want to be accepted in their true gender without being defined by a past most would rather forget.

The necessity for this discussion has arisen from the debate surrounding Girl, a Belgian film by Lukas Dhont which depicts the medical transition of a 15-year-old ballerina named Lara, played by Victor Polster.

Regardless of criticism, it can only be good that we are talking about and raising awareness of what it means to be transgender. The problem arises when people take this to be a singular experience that can be encapsulated in a piece of art. For Lara, her genitalia are the focal point of her body dysphoria, while for others it might be their face, voice, or a general overwhelming discomfort in their own skin.

Her image dysmorphia is related to implications of anorexia and constant body checks in the mirror, a realistic portrayal of a large number of people going through gender transition. This is not a universal case, for there is no such thing, but it is that of dancer Nora Monsecour upon whom the film based. To claim that it is not genuine is disrespectful of her testimony.

Controversy particularly surrounds the drastic action Lara is shown to take after her body becomes too fragile for gender reassignment surgery to be feasible. Words cannot express how devastating being told that this procedure needs to be delayed can be for those whose transition revolves around it, often leading to dark and suicidal thoughts.

In the film, Dhont has elected to represent these feelings through an act of self-harm which can be read as the inevitable culmination of Lara’s dysphoria. Rather than intending to make an audience squeamish, the focus of the camera upon her crotch mirrors her own obsession, constantly aware of that which is preventing her from living as her true self. Especially in the binary world of ballet, the comparisons drawn by the camera between Lara and the other girls is not Dhont’s criticism, but that of Lara herself.

Beyond writing on this specific film, there is an inherent problem in the branding of men and women as cis or trans. It becomes an error when writers criticise Dhont as a ‘cis male director’, Victor Polster as a ‘cis male actor’, despite neither identifying themselves as such. In doing so, it is made clear that there is a notion of difference for filmmakers who are ‘trans’. This barrier created by language must be overcome if people who have transitioned are to be accepted in the gender they inherently are.

To say that a trans person can only play a certain character or make a film, or even be a critic of these films, forces one to expose one’s medical history in order to qualify oneself to have a voice. I am a female critic – if you were to enquire whether or not I have transitioned would be a violation of my privacy. It is surely impossible for people who have transitioned to be given equal opportunity if they are constantly having to justify their right to speak.

Before seeing Girl, I had already decided that the film was an abomination. I held a strong view that only someone transitioning, or someone who identified in the true gender of the protagonist could successfully tell their story. Tilda Swinton’s absurd turn as a German man in Suspiria, for example, demonstrates the insulting idea that someone of an assigned gender can portray another. The same can be said of non-binary identities, if any filmmaker bothered to cast or represent such people.

Indeed, it is the notion of binary gender which makes discussions of casting uncomfortable. When critics brand Polster as a ‘cis actor’, they imply that he was born into a specific mindset and form of life that prevents him from having any sensitivity to female experience. The issue with Polster’s casting is rather that he is portraying a girl on puberty blockers, which would prevent Lara from developing some of the masculine features highlighted in the film. While he gives a very respectful performance, it is still undeniably one that should have gone to a female actor.

Girl is not the first film attempting to grapple with these issues. In 2017, Sebastián Lelio directed A Fantastic Woman, whose protagonist’s transition is only made an issue of by other people. The extremity of the transphobia made it a film I had on first viewing dismissed for being irredeemably bleak. On the contrary, by celebrating Marina’s (Daniela Vega) talent for singing, the film does not reduce its central figure to an object of fetishisation, which has been portrayed as being the case especially when women choose not to have reassignment surgery.

A Fantastic Woman, however, sets itself up as an unabashed love story as the audience feels the romance between Marina and her partner Orlando (Francisco Reyes). It is his unquestioning acceptance of her that makes the later deadnaming, violence, and nauseating description of Marina as a ‘chimera’ hit hard – it is so painfully and obviously false.

Avoiding this problem, Girl is clear but necessarily subtle in its distinction between gender and sexuality. Lara’s father (Arieh Worthalter) clearly does not mind who his daughter is attracted to, and delightful conversation in a car sees her purposefully mystify who she fancies – the point being that at her age she still isn’t sure.

Lara’s experience of something approaching a sexual awakening no doubt exacerbates her dysphoria, and makes her more sensitive to misgendering, but also acceptance, as in a delightful scene when her brother’s teacher asks if she is his sister and the camera focuses on her beaming face as she walks away. Girl also effectively captures the moment of mental error when family members in frustration deadname their loved one – the heart-breaking tears that follow remind us that friends and family must also go through a difficult transition process.

The hardest scene to watch in A Fantastic Woman is one in which Marina attempts to pose as a man in order to enter a spa. She remains obviously female, and Vega’s courage to expose herself in this way goes beyond the usual challenges of acting. This performance must have taken its toll on Vega, who at 29 would perhaps possess greater psychological stability to get through the scene.

With Girl, the fragility of a child beginning their transition would worsen the turmoil that constitutes gender dysphoria. Because we need films depicting the process itself for people to understand the difficulties it can bring, the casting of an actor not undergoing treatment was essential. I reiterate – a girl would still have been better positioned to play this part with authenticity.

I not attempting to rebut specific writers because I have no right to undermine their personal responses to seeing these films. As already mentioned, Girl is a film which has been the subject of widespread criticism, covering the gamut from positively skewed reviews to nakedly personal reflections on the ways in which the film articulates its drama and represents its characters. Throughout the debate there seems to have been a general misunderstanding that there are no people whose transition resembles that of Lara in the film. It certainly seemed like this for Nora Monsecour, who must feel targeted by the furious criticism aimed at the film.

By telling her, and other men and women whose transitions are or were similar to that shown in Girl, that their experience is not that of a transgender person is itself dangerously transphobic. My only hope in writing this piece is that writers choose their language more carefully – prefixing ‘man’ or ‘woman’ with ‘cis’ or ‘trans’ only serves to deny equal opportunity. Some people do comfortably identify themselves in this way, for it is perceived as necessary to label oneself to demonstrate that a voice is being represented.

But for those who have transitioned seeking only to be perceived as men or women, there is no need or obligation to reveal sensitive medical information so they can be allowed to do their job.

Both of these films choose to end with Handel’s aria ‘Ombra Mai Fu’. In A Fantastic Woman, Marina performs the piece at a concert, and an orchestral arrangement is heard as Lara walks down a passage in the final scene of Girl. The aim is to be optimistic, to celebrate art in their lives and bring hope for the future after a period of trauma. Both scenes are clipped on as a rushed epilogue – the use in Girl is particularly jarring as it follows an unjustifiably disturbing act. A less emotionally obscure ending could have seen Lara happy in her pointe shoes giving a recital, similar to the short performance at the end of Billy Elliot.

Instead we hear an aria composed for soprano castrato, the implications of which are clear. The films then reduce their heroines to suggest that they have merely been castrated and remain male. This is almost certainly not the intended message, but it does demonstrate the importance of extreme sensitivity and attention to detail when dealing with such a delicate subject, especially when it has the potential to trigger audiences. I dare say these are issues to which critics might pay better attention.

Lara and Marina face extra difficulty in careers that we as critics ought to applaud – opera and ballet. As already challenging fields, we should not be adding obstacles to their entry into the environment in which they will thrive – the same of course applies to acting. In art as in life, if we insist that people who have transitioned can only take on the roles of ‘trans’ people, it follows that no one who has transitioned can perform the roles of those who have not. This situation would only serve to narrow access to already oppressive sectors of work.

Progress is not in films that deal directly with medical and social transition, although they are important, but ones which do not make an issue of the subject altogether. Neither Marina nor Lara is termed a ‘trans female’ in the films, and yet more-or-less every review of both films branded them as such. These films are actually about a woman who wants to sing, and a girl who longs to dance. By fixating on gender as the transphobic characters do, we ultimately reduce their talents and personalities to the medical process they have undergone.

Published 19 Mar 2019

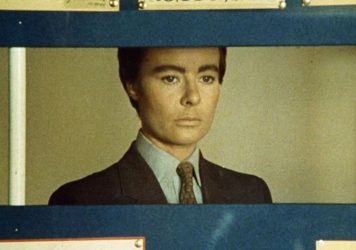

Findings from a rare public screening of John Dexter’s I Want What I Want.

A star is born in Sebastián Lelio’s drama about a trans woman coming to terms with the death of her partner.