Thanks to the constant development and expansion of the internet, we have now reached a point where we are able to project identities and personalities that do not truly reflect the lives we lead. But what if technology advanced to the point that our minds could roam free, no longer shackled by the limitations of a human body? That is the central dilemma of Mamoru Oshii’s classic 1995 anime, Ghost in the Shell.

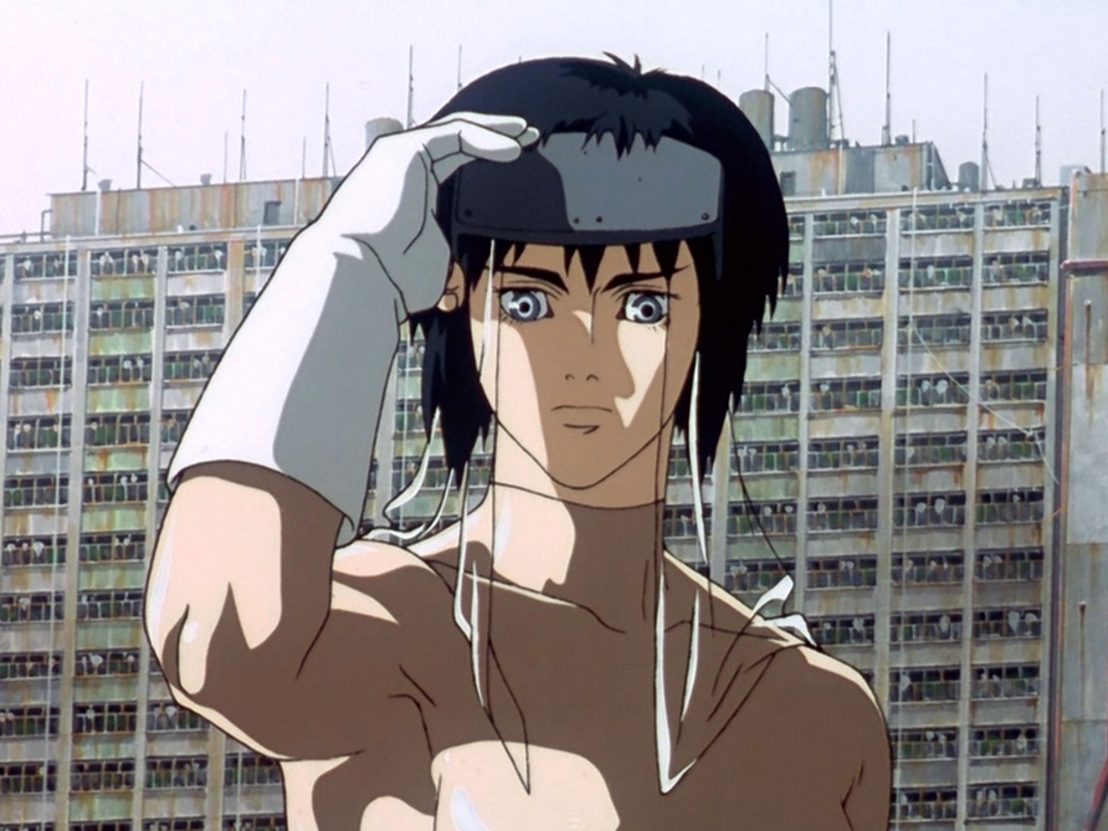

Our hero, Motoko Kusanagi, is a cyborg police officer tasked with leading an anti-cyber terrorism unit in a futuristic Japanese city, where everyone is connected to a mass electronic network. People can access this data field through their artificial bodies, otherwise known as ‘shells’. One of the few remaining biological aspects of these bodies is the brain, which retains a conscience that is known as a ‘ghost’. Motoko and her team are on the trail of the Puppet Master, an elite hacker who has the ability to access the minds of other cyborgs in this world and use them to do his bidding. His emergence, and the idea of entering another body, pique Motoko’s interest while providing the film with its narrative drive.

In order to analyse the identity crisis at the heart Ghost in the Shell, it is important to consider the surroundings in which the story takes place. Thirty minutes in there is a four-minute sequence that guides us through the city. The original cityscape still stands but has been left to ruin in the shadow of impossibly huge skyscrapers, which look more like machines than buildings. The feeling of constant change lingers long after this scene, as the people continue with their daily lives practically oblivious to the cultural conflict that is happening around them.

During this scene, we see Motoko travelling on a boat through the city’s canal system. She gazes at the buildings and those around her, not with contempt but melancholy. At one point she spots another girl, who is the spitting image of her. They observe each other without registering an emotional reaction. This is the only hint that Motoko might be a model assembled on a factory production line, defined only by her mind. It is only a passing moment but one that conveys a strong sense of loneliness and detachment.

Motoko lacks any discernable personality traits and shows no real understanding of human emotions. She often appears nude in front of colleagues, which symbolises her vulnerability while also emphasises the fact that she has no concept of what it means to expose oneself publicly. Her partner, Batou, averts his eyes on more than one of these occasions and even covers her up with his coat. Motoko doesn’t wish to cause Batou any embarrassment nor does he want to feel like he is exploiting her body.

Gender is another issue within the complex workings of Ghost in the Shell. Despite having a female body and an effeminate voice, it is unclear whether Motoko identifies herself as a woman – or even as a human. During the stunning opening credits sequence, we witness the formation of her body and see that she has no genitalia. At one point she jokes about it being her “time of the month” but we are well aware that she lacks the functions to menstruate. That moment, along with a few admittances of showing emotion, tells us that she desires to be human. But that changes when she finally meets the elusive Puppet Master.

When she first encounters him, he is occupying a female shell – not out of choice or necessity but purely for its functionality as a tool. The Puppet Master then claims that he is a form of artificial intelligence that has become self-aware. With that revelation comes a profound piece of thinking: the Puppet Master tells Motoko that searching for oneself is impossible because individuals are constantly changing, therefore trying to obtain a perfect identity is irrelevant. He encourages Motoko to merge with him and abandon her search in order to create a higher life-form that isn’t restricted by the boundaries of body and mind.

Motoko’s evolution is a multi-layered exploration into the very essence of existence. The divisions that separate ghosts and shells are meticulously dissected in the film, leading to an avalanche of metaphors and dense dialogue. The scope of Oshii’s film knows no bounds and new ideas are revealed in repeat viewings. There may be more concise investigations into identity in the history of cinema, yet Ghost in the Shell remains the among the most fascinating and rewarding.

Published 18 Mar 2017

Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s iconic anime mirrors the atrocities witnessed by Hiroshima and Nagasaki 70 years ago.

By Alex Denney

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s eerily prescient 2001 film journeys to the heart of technological darkness.

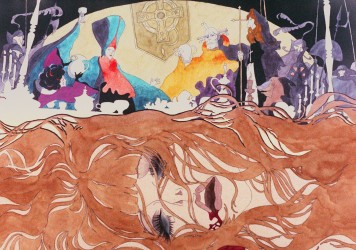

Look out for Eiichi Yamamoto’s transgressive epic from 1973, Belladonna of Sadness.