What do you feel upon hearing the sound of an internet dialup tone? A little frisson of nostalgia, perhaps? A sense of despair at how far down the rabbit hole we’ve fallen? Regret for any of the above?

Listening to the once familiar crush of clicks, whirs and scratches that open Pulse, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 2001 J-horror, you might be inclined to laugh: are we supposed to feel afraid? But perhaps there’s something else going on here. After all, what is a dialup tone but the sound of humans trying to communicate? “People don’t really connect, you know,” muses one poor soul in Kurosawa’s film, a tour de force of technological angst whose eerie prescience only seems to grow with time. “We all live totally separately. That’s how it seems to me.”

Long, lugubrious and audaciously bleak, Pulse is the work of a man once admiringly charged with making “existentialist tone poems in the guise of entertainment”. Which might be stretching most people’s definition of entertainment a bit – the glacial pace alone will terrify some viewers more than anything in the film. For those who like their horror big on atmosphere and metaphysical subtext, however, let’s just say you’ve come to the right place: this film is like Andrei Tarkovsky reimagining Ringu as a Cormac McCarthy-esque apocalyptic fable.

The story is strangely difficult to define, the gist being that the souls of the dead have started spilling out of computers and into the streets of millennial Tokyo, prompting a mass existential crisis that is pushing people to suicide. (In one deeply disturbing scene, an anonymous woman throws herself from a water tower while a character texts on her phone in the foreground.) But what makes Pulse such a fascinating journey into the heart of technological darkness is the way that Kurosawa spins this bare bones plot into a profound meditation on the way that computers reflect our loneliness back at us.

Of course, ideas about the alienated self are in no way bound by discussions of technology. It’s also true that Japan, still reeling from recession, was gripped by a wave of suicides in the late ’90s. Moreover, the internet of 2001 bore little resemblance to the all-pervasive beast of today – at the time of Pulse’s release, online time was generally confined to school computer suites and spare moments when someone in your family didn’t want to use the house phone. “I wrote this film (as) the internet was just starting to become popularised,” Kurosawa said in a 2005 interview. “It was before anybody really had a full idea of what effect it was going to have on our daily lives… I think at the time it was just kind of this unknown force that was spreading like a virus throughout the country and had that kind of ominous and menacing feel to it.”

Whatever the intent, Pulse is scarily on the money, bristling with images that anticipate the alienation of our hyper-connected digital age. In 2016, researchers are talking up an epidemic of loneliness linked to increased internet use, and it’s a spectre that stalks every frame of Kurosawa’s film.

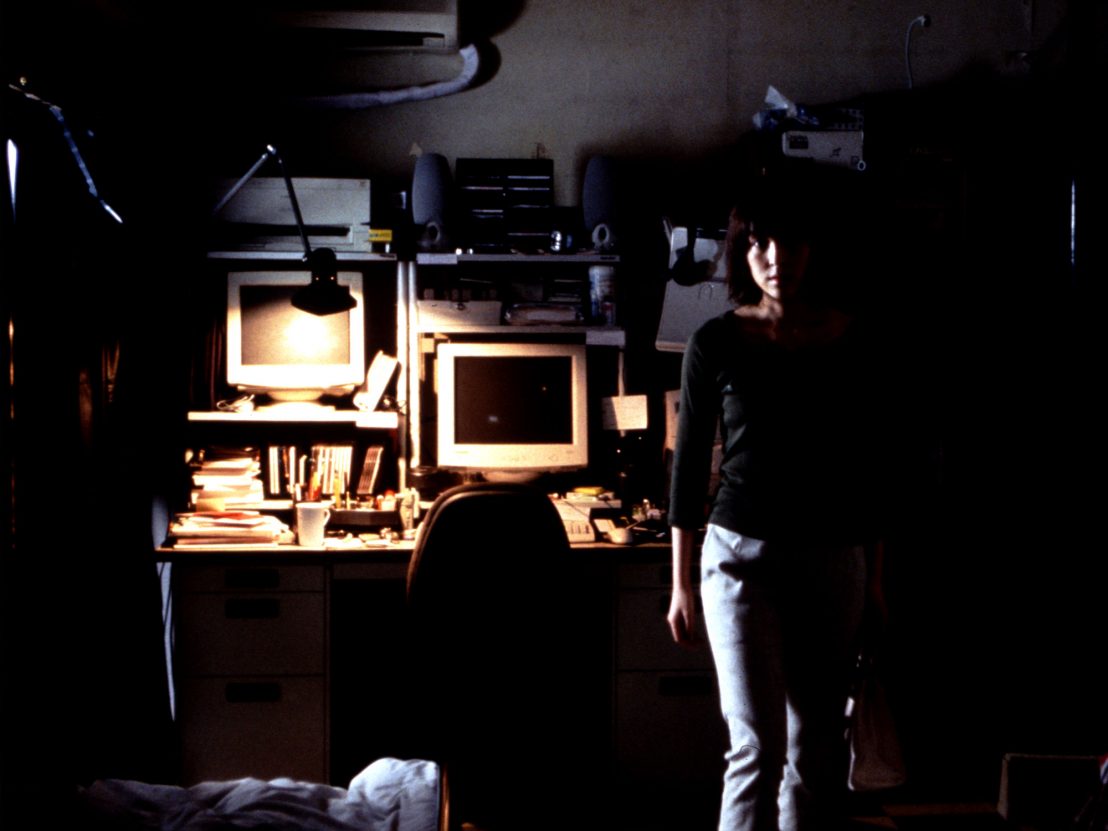

In one haunting sequence, a computer sciences student, Harue (Koyuki), sees an image of her hallway in her computer screen. Is there something out there? She goes to find out, throwing her arms around a phantom presence lurking, it would seem, somewhere behind the camera. “I’m… not alone!” she whispers ecstatically, drunk on the illusion of connection. Needless to say, things don’t end well for her.

In another scene, a computer disk reveals an image of a man staring silently at a monitor displaying the exact same image, creating a hall-of-mirrors effect rippling off into infinity. In troubling images such as this – and in artfully framed shots spying on his cast from behind windows and supermarket counters – Kurosawa intuits a world where URL/IRL distinctions have collapsed, and people are plagued by a constant, creeping feeling that they’re being watched. And if that sounds familiar, it should.

But there is another way to interpret Kurosawa’s apocalyptic visual style. “Once the system is complete, it will function on its own,” says one kid of the ghosts’ inexorable march into the real world. “It will become permanent. There’s no turning back.” In another film, this would be a makeweight bit of dialogue conveying urgency to the viewer. In Pulse, it’s merely an acknowledgement that, once the Pandora’s Box of technology has been opened, there’s no going back.

Read this way, the film becomes a sweeping comment on the struggle to find new ways of being in the face of cataclysmic social change. “I think the vague idea I had at the time was that we were really on the cusp of a new century,” said Kurosawa in 2005. “The idea was to abandon, by destroying everything from the 20th century in order to head into a good, new future. It wasn’t that the apocalyptic vision was negative or despairing, it was positive, a way to get rid of old baggage.” In 2016, the thought of a world untouched by the compulsive rhythms of life in the digital age seems fantastical – ridiculous, even. But, Kurosawa’s film reaches out of the screen to ask, have we really got the hang of living in this one?

Published 11 Dec 2016

By Alex Denney

Films like Arrival and Paterson have plenty to say about the importance of learning how to listen.

Directors Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick tell the story of how their freshman film project became a cultural phenomenon.