While the big-screen western is now an intermittent treat, there is still plenty to be said for the powerful and potent ways in which the genre contends with the darker heart of the American experience. In television, the genre continues to find a welcome place and it’s fascinating to chart. Perhaps Westworld, and the recent series Godless and Yellowstone, will fuel an ongoing smallscreen western renaissance. There’s still so much that the genre can handle.

Released in 1993, Walter Hill’s Geronimo depicts the litany of acts of violence and aggression that constituted the genocide of the native- American culture. Intriguingly, Hill’s film arrived just a few weeks before another American studio film chronicling a historical genocide, Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.

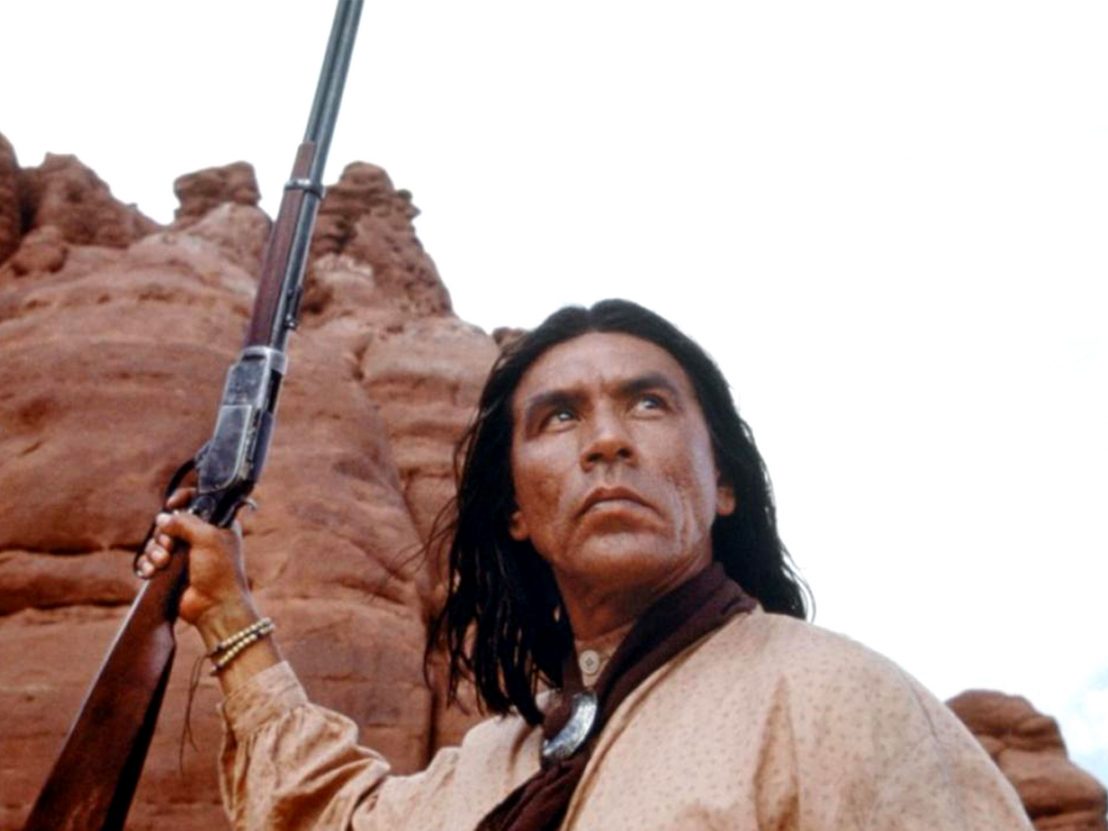

Geronimo , based on a screenplay by John Milius and Larry Gross, and developed from Milius’ screen-story, recreates aspects of the US military’s mission to capture Geronimo and his Apache tribe between 1885-86 as part of the US policy of resettling native peoples on the reservations. Five thousand troops were committed to the task of bringing Geronimo in as white political and military power went about deeply unsettling the west.

Like Schindler’s List, Geronimo explores the hateful expression of racially-motivated violence. Where the latter takes earlier Hollywood westerns, as well as the 19th century photographic record of the West, as its visual cue, Schindler’s List draws from Italian neorealism and the photographic record of the Holocaust. Both films present us with a distinct culture and the destruction of the places and traditions held most dear by them.

A number of initial reviews of Geronimo noted that the film was a little plodding. Is it not fairer to say that it is hard to watch because of the reality that it seeks to present? The film’s closing voiceover, spoken by Matt Damon’s character, the young soldier Britton Davis, tersely describes the genocide that the film has depicted: “A way of life that endured over a thousand years was gone.”

While Milius was frustrated by the eventual form that Geronimo took, his atavistic impulses shine through in the film, as does his affinity for the figure living outside of, and resisting, the bounds of so-called ‘civilisation’. In a key scene, Wes Studi’s eponymous Apache protagonist states, “No guns, no bullets could ever kill me. That was my power.”

At the heart of the film’s second act is a moment that crystallises the precarious existence of Native American culture in the wake of the white unsettling of the West. The film details Geronimo’s commitment to upholding his culture. Schindler’s List too evokes the importance of cultural memory and identity for its beleaguered protagonists – the very first scene in Spielberg’s film shows a Jewish family at Shabbat, and later on, when Stern tells Schindler that the list is an “absolute good”, the document is presented in such a way as to assume an almost-ancient and sacred power. That same sense of ancient and sacred power is key to understanding the Apache people’s relationship with the land.

Within the demands of its genre mechanics, Hill saw an opportunity for Geronimo to be, “Implicitly critical of all previous depictions of white-Native American relations.” His film is marked by a vivid sense of mounting melancholy and tragedy, both personally and nationally. Around the time of the film’s release, Wes Studi, in all his anger and sadness, addressed the tension between Native Americans and their white settler oppressors: “I’m a Cherokee first and an American later.”

Of course, the destructive collision of white American culture with native, non-white communities continues to this day. Indeed, 16 years later Studi portrayed a Na’vi tribal leader in James Cameron’s Avatar. That film, like the historical dramas mentioned here, reframes various attempts to eradicate different cultures within a futuristic fantasy setting. The past is always alive in the present. We forget this at our peril.

Geronimo was eventually released in the UK in October 1994. More specifically, it was released in London. In one cinema. More than two decades later, it’s time to rediscover this largely forgotten film, and consider its status as a progressive western that openly confronts a national trauma.

Published 11 Aug 2018

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.

With global nationalism on the rise, now seems like the time to revisit Claude Lanzmann’s masterpiece, Shoah.

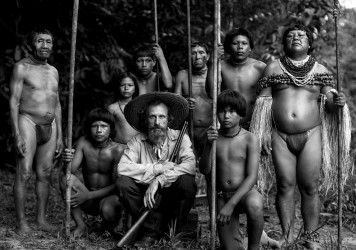

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.