At its core, film noir inverts the detective genre, taking tales of analytically ingenious investigators solving impossibly elaborate cases and turning them inside out. The hardboiled stories of Prohibition that birthed it brought stark realism to the world of the whodunit, or, as Raymond Chandler wrote of Dashiell Hammett’s brooding and morally ambiguous adventures, “gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought duelling pistols, curare, and tropical fish.”

Released 60 years ago, Elevator to the Gallows (aka Lift to the Scaffold) had all the grit that the nocturnal streets of 1950s Paris could offer, but Louis Malle’s directorial debut also inverted the classic whodunit structure. The suspense in Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders on the Rue Morgue – published in 1841 and credited as the first detective story – hinges on the proto-detective C Auguste Dupin steadily unravelling the mystery of a double homicide committed in a room locked from the inside (spoiler alert: an escaped orangutan did it).

But Elevator begins by taking us inside the locked room where protagonist Julien Tavernier murders his arms dealer boss Simon Carala with the intention of running away with his wife, Florence. Opening with a phone call in which Florence repeated tells Julien “Je t’aime,” and a full of view of him arranging Carala’s body to look like a suicide before descending by grappling hook back to his own office on the floor below, Malle gives us means and motive in the first ten minutes. How, then, does he hold our attention for the next 80?

Partly through a series of incidents that sees each of the film’s characters hurtle off in his or her own unhappy direction, partly through withholding if and when they’ll be brought to justice. Arriving at his car following the murder Julien realises he left his grappling hook at the scene, and in a turn worthy of Hitchcock gets trapped in the elevator as he goes to retrieve it and a security guard shuts the building’s power off for the night.

Finding that Julien has left the engine of his flashy Chevrolet Deluxe running, young couple Louis and Véronique take a joyride that ends up with Louis murdering an older German couple with whom they spend the night partying. Meanwhile, having seen Julien’s car pass by with a young woman in the passenger seat, Florence assumes the worst and spends the film wandering the streets of Paris, accidentally incriminating Julien for the murder of the German couple when – having been picked up by the police in the early hours – she mistakenly identifies him as the driver of his own stolen car.

None of this amounts to much of a plot, though, and certainly not to the airtight storytelling of your typical hard boiled tale or psychological realism that characterised French cinema previously. Instead, Malle performs another inversion, turning his characters inside out and using the means at his disposal to splay their moods across the screen. He does this in large part thanks to the legendary soundtrack by Miles Davis, improvised around sparse harmonic sketches the King of Cool made during a private screening. In the minimal modal jazz harmonies that characterised records like ‘Kind of Blue’ (released the same year), rather than the more complex Bepop or Cool sounds he had championed previously, Davis simultaneously brought style and depth to the film’s most significant scenes.

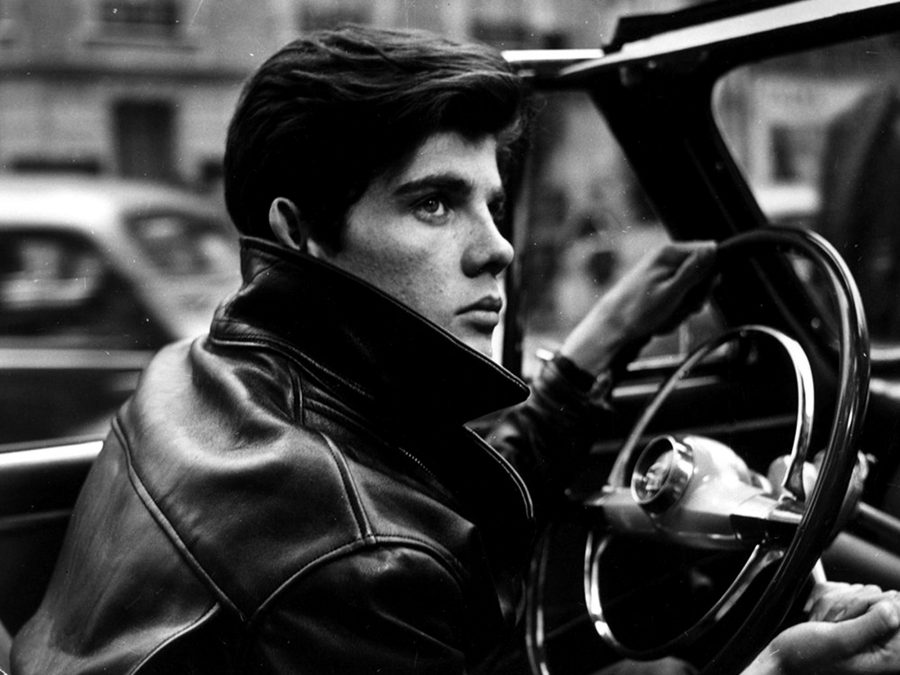

His expressive tones most notably accompany the recurring sequences of Florence traipsing the Champs-Elysée, languishing after Julien, which were shocking at the time for Malle’s decision not to light Moreau in the traditionally flattering way, but to let street lights, flashing signs and strip lights illuminate her angst. In another scene whose shaky shots and similarly trumpet-laden soundtrack directly influenced several sequences in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, as Louis and Véronique drive their stolen car out of Paris Malle’s restless camera captures the instability of a new post-war generation, simultaneously cocky and in search of itself. Complemented by frequent references to problematic moments in recent French history – Occupation, Indochina, Algeria – the script is replete with role reversal. War-generation Germans and powerful arms dealers fall victim to not-so-innocent youths and, in Julien’s case, a war hero-turned-criminal.

Using bold techniques to show conquerors become casualties and kids turn criminal, Malle relentlessly questions and inverts the cinematic status quo in ways that would characterise the Cahiers du Cinema generation of filmmakers that followed, even if – as the heir to a sugar fortune – he was every bit the haut-bourgeois they hated. Whether we call Elevator the first film of the New Wave, or its direct antecedent, it anticipates the movement by substituting tight plotting for unconnected incidents and stylistic innovation. When the story does eventually come together, following a deeply expressionistic scene in which Julien is grilled by the police in heavy chiaroscuro – suspected of one murder for which his alibi would incriminate him for another – it is in a photographic lab.

As Louis and Florence arrive, intent on destroying the evidence and unaware that a detective is waiting for them, the photo negative that ties each character to his or her crime develops before our eyes into a damning deus ex machina. It isn’t the most convincing ending, but then, as Godard would later quip, “The Americans know how to tell stories very well; the French, not at all.” In place of plot, he and his peers brought style and a different kind of substance, and much of this began with Louis Malle’s superlative crime noir.

Published 29 Jan 2018

The Lady from Shanghai is a prime example of the legendary filmmaker’s complicated genius.

This early work from the French New Wave icon is a must-watch for cinephiles.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.