By the time Charlie Chaplin unveiled The Circus at the start of 1928, cinema was already under the spell of the ‘talkie’, the release of The Jazz Singer having sounded the death knell for the silent era three months earlier. Chaplin’s financial autonomy allowed him to retain his silence in the intervening years, but both 1931’s City Lights and 1936’s Modern Times featured moments of speech and synchronised sound. By 1940 Chaplin finally succumbed to popular convention with The Great Dictator, making The Circus his last truly silent picture.

Even without the added complications that came with shooting sound, The Circus was Chaplin’s most troubled production, taking close to two years to complete. A simple enough premise – the Tramp joins a travelling circus – didn’t appear to offer any major logistical problems, while shooting in his own studio and on his own bankroll gave Chaplin all the freedom he needed. But things quickly began to conspire against the director. The circus tent where much of the action takes place was destroyed by bad weather, poor handling of the film negative made early footage worthless, and Chaplin’s studio was decimated by fire. However, it was only when Chaplin’s famously fraught personal life came under the spotlight that the film’s future became uncertain.

Chaplin’s marriage to Lita Grey had broken down, and the eventual divorce proceedings delayed production indefinitely. The film was aimed to be seized as assets, prompting Chaplin to smuggle the reels into safe hiding – the second time he was forced to do so following a similar incident during the making of 1921’s The Kid. The stand off over The Circus lasted for eight long months, with Chaplin suffering a mental breakdown in the process that caused his hair to turn white, making him virtually unrecognisable outside of his Tramp guise. This extended break in filming led to still further problems, as the real estate boom had transformed the existing landscape. Meanwhile, one of the circus wagons was stolen as Chaplin prepared the final scene.

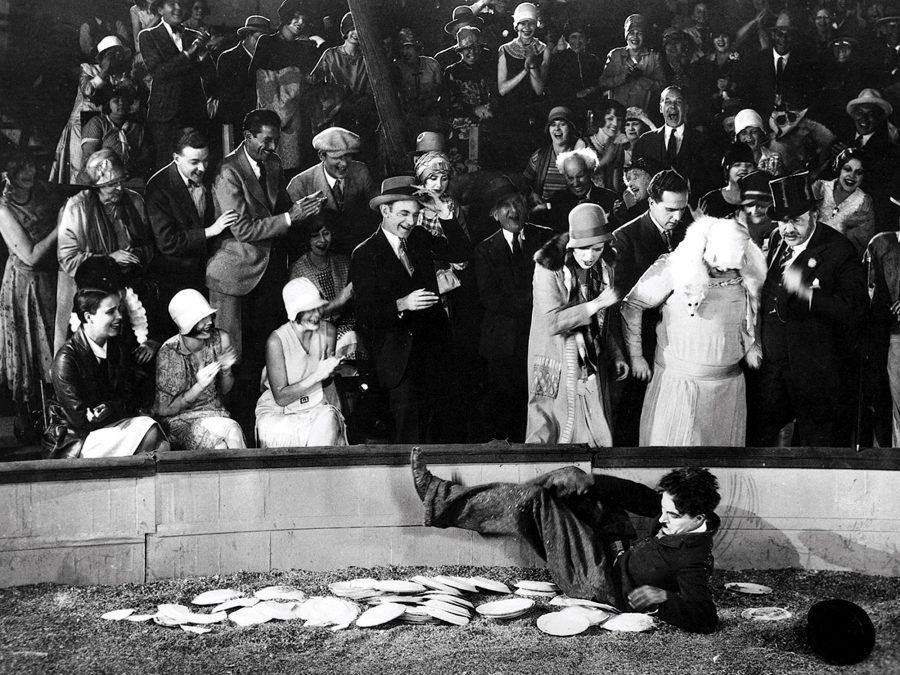

All this may have driven Chaplin to breaking point, but secretly he revelled in seeing the Tramp causing chaos, understanding that when things go wrong, it becomes more hilarious for the audience. Things going awry is only to be expected whenever the Tramp is involved, and in getting caught up in the circus, the character finds fame as only he ever could – through failure. Chaplin’s method of not working from scripts but instead following ideas through to their conclusion led to the film evolving into a glorious balancing act of set pieces, with Chaplin’s skill as both performer and director shining through. It’s chaos, yes, but meticulously constructed chaos.

An early scene in which the Tramp imitates a fairground automaton showcases Chaplin’s supreme understanding of cinematic rhythm, and another where the Tramp finds himself inside a lion’s cage reveals a rare level of commitment and meticulousness. The latter scene was filmed in 200 takes, with Chaplin often positioning himself a whisker away from the lion – but even that pales in comparison to the film’s pièce de résistance, the climactic tightrope walk. This extraordinary sequence was dreamed up early on by Chaplin, and would become one of his most daring feats. It sees the Tramp perform a tightrope act through the help of a hidden wire, only for the cable to snap, leaving him completely unaided with a long way to fall. Chaplin doesn’t stop there though, throwing in a swarm of monkeys which writhe over him, biting his nose, putting their tails in his mouth and proceeding to remove his trousers.

Remarkably the scene in question took over 700 takes to complete, though this gargantuan number is partly due to part of the film stock being damaged. Still, the physicality required to perform this sequence, time and time again, is staggering – especially given the continued subjection to monkey assault. Such exertion was clearly not something Chaplin savoured, as he gives no mention of the film in his autobiography, despite having received a special award from the Academy for writing, acting, directing and producing for his efforts. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Chaplin eventually found reconciliation with film, as he returned to it some years later to compose a new score.

Chaplin suffered greatly to bring The Circus to the screen, and its protracted production ensured he was well aware of The Jazz Singer and its seismic impact. At the end of his film, the circus packs up and leaves town, the Tramp watching on before heading off in the opposite direction, alone. The Circus not only showcased Chaplin’s comic genius, providing some of his most iconic images, it also reaffirmed his desire to do things on his own terms. This great silent clown would not go so quietly.

Published 27 Jan 2018

By Lara C Cory

Portishead’s Adrian Utley and Goldfrapp’s Will Gregory discuss writing new music for The Passion of Joan of Arc.

Contemporary Hollywood could learn a thing or two from Preston Sturges’ progressive and daring film.

Director of the Close-Up Film Centre Damien Sanville offers a possible route to a 35mm revival.