If life is a cabaret, Bob Fosse’s imaginative film version of the Broadway musical ‘Cabaret’ reflects humanity at its most vulnerable and perplexed. It offers a devastating chronicle of a society losing its liberal bearings and skidding toward a totalitarian abyss. Fifty years since the film’s release, its uneasy themes, leavened by exuberant musical numbers, have lost none of their urgency.

We are in the delusional, final chapter of the decaying Weimar Republic of 1931. Kit Kat Klub’s innocent decadence bounces against the War Guilt Clause, hyperinflation, and the joyless street. Bohemian lifestyles flourish, nocturnal excesses abound, and quick money cascades freely. There is no tomorrow. That is, until a song comes along at a folksy beer garden, performed ad hoc by a Hitler Youth member: ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Me’. Cabaret highlights a turning point in history when reason was officially abandoned.

In the middle of it all, Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli), an American expat entertainer, and a young English scholar, Brian Roberts (Michael York), engage in an unlikely dalliance. Both characters bear only faint resemblance to Christopher Isherwood’s original literary creations from ‘The Berlin Stories’. In Fosse’s picture, Sally is a dynamo on the cabaret stage and a boudoir freewheeler. As portrayed by the wondrous Minelli, Sally’s faux-vamp veneer is a frisky act of a woman navigating a man’s world.

Her sexual liberation feels like a chair-straddling pose borrowed from Marlene Dietrich’s Lola Lola. Sally is driven in equal measure by survival instinct and cheerful naiveté. Despite her Louise Brooks helmet haircut, a calculating Pandora she is not. Tender, vulnerable and energetic, Minelli’s instantly iconic performance brims with emotional intelligence; she was justifiably honoured with one of the eight Academy Awards received by the film.

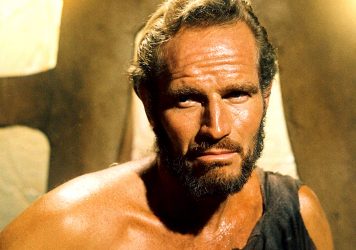

Brian is the odd man out. As a young intellectual searching for exotic experiences in Berlin, he is Sally’s polar opposite. Played with great restraint by Michael York, Brian glides through the film like a removed spectator – both physically and emotionally. Eventually, he lets his feelings cautiously loose. But, for this man, even discovering bisexuality is more of an act of clinical curiosity rather than a need for self-identification. After a rare display of political pique, Brian takes a beating for kicking a Nazi flag. Yet, ultimately, the idealistic Englishman dismisses fascism as a mildly annoying “international conspiracy of horses’ arses…”

Then, there is the Kit Kat Klub. Paradoxically, it is the venue’s theatrical stage which makes Cabaret such a rewarding cinematic experience. Fosse’s method is to entirely dispense with glossy Hollywood musical traditions. Outside of the club, nobody spontaneously breaks into plot-propelling song-and-dance routines.

Instead, the film’s marvellous cabaret numbers serve as a dynamic counterpoint to the dramatic storyline. The pounding heartbeat of the film belongs to Fosse’s phenomenal staging of the Kander & Ebb songs. The omnipresent, constantly flowing camera observes the performances from all imaginable angles. Each song is given unique visual arrangement.

In ‘Mein Herr’, a number written specifically for the film version of Cabaret, every phrase is punctuated by editing. Singlehandedly, Fosse introduced a new template for the film musical – making it almost a participatory experience for the audience.

Minelli and Joel Grey, as Master of Ceremonies, are simply astounding – separately or as a duet, they balance the musical’s entire account with so much verve and charm, the ugliness outside loses its grim edge for a time. And that is precisely the point. Influenced by New Objectivity art of George Grosz and Otto Dix, the cabaret performances satirise big business and corruption, hedonism, and the militant edge of the far right.

But there is nothing satirical in Fosse’s treatment of real violence and antisemitism. Even though it comes on screen only in brief spells, menace is constantly brewing below the surface of public complacency. With its dark tone veiled in musical brilliance, Cabaret succeeds beautifully as an indictment of self-serving oblivion without ever feeling didactic.

Reprising his role from the Broadway production, Grey crafts one of cinema’s most memorable characters. There is that pliable face, the note-perfect cadence of singing, and flawless comedic timing enhanced by Fosse’s clockwork choreography. Subtlety was not exactly built into this part, but the camera allows Grey to find plenty of nuance in MC’s flashy outrageousness. It is through him, not Sally or Brian, that Cabaret delivers its painful catharsis.

When during the final performance MC trains his eyes on the audience, you can feel his horror at playing to a room of ghastly apparitions. He sings as much to them as about them – a defeated Pied-Piper failing to lead his audience out of collective insanity. The only thing left is to gracefully bow out. The stage is now set for a new cast of grotesque performers. Brownshirts and Nazi officials, reflected in a distorting mirror, await a new Master of Ceremonies to enter the spotlight. Tomorrow belongs to him.

Half a century later, Cabaret continues to play like a thoroughly modern film. It is at once energetic and dreamy, yet filled with an overwhelming sense of despair. Times might have changed, but our world is still full of gnarled faces awaiting a leader who would make their fatherland great again.

Published 13 Feb 2022

By Adam Scovell

With The Young Girls of Rochefort, the French director created something wondrously original.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

Franklin J Schaffner’s satire was a response to an era of social upheaval.