Bruce Lee died on July 20 1973 and Enter the Dragon premiered in Los Angeles a month later. The contrast was startling, the irony evident: on screen, Lee looked more alive than any other action star, and he was dead by the time of its premiere.

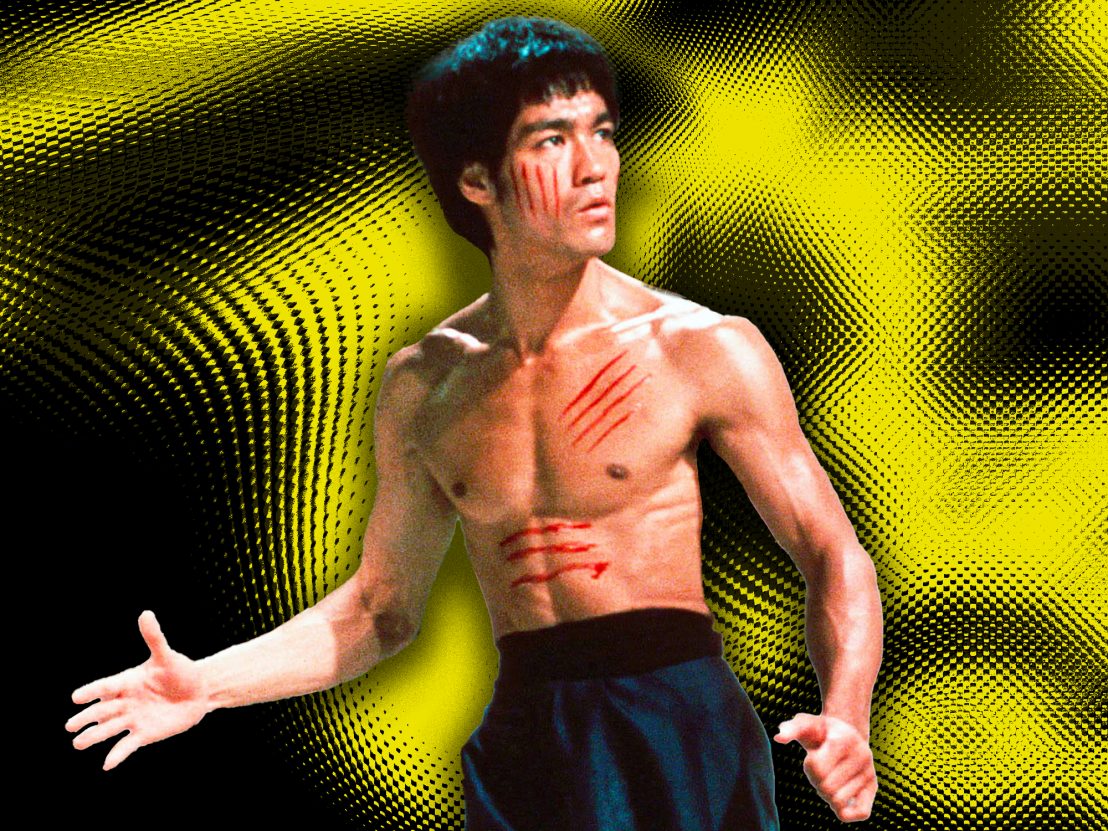

Strange circumstances, but Enter the Dragon is strange. It’s a poorly-shot kung-fu flick made on a bargain budget, starring a Chinese-American named Bruce Lee who’d found some fame in mediocre Hong Kong productions and gigged as a Hollywood kung-fu teacher while trying to become, in his words, “the first highest paid Oriental superstar in the United States.” Lee was preceded in Hollywood by other Asian actors – Anna May Wong, Sesue Hayakawa, Nancy Kwan, etc. – but Lee was the first Asian actor to avoid being typecast as villain or feyish morsel. He was treated like someone cool. Cooler than Connery’s Bond, cooler than McQueen’s Captain Hilts, cooler than Elvis in any of his roles, which is another way of saying that Bruce Lee was the first Asian actor that Hollywood presented as a nonethnic sex symbol. Lee’s contemporaries were Brando, McQueen, Marilyn, Elvis: film icons as bedroom fantasies. In 1973 American audiences added Bruce Lee to the list.

In Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee plays the aptly-named “Lee”, a plainclothes Shaolin monk moonlighting as an international secret agent. Lee is hired by a British security agency to infiltrate a mixed martial arts tournament run by “Mr. Han”, a disgraced Shaolin monk who installed himself as lord of a small island, got himself a big, board-breaking bodyguard named “O’Hara”, and entered the sex-and-heroin trafficking business. In classic movie hero style, Lee does much more than he’s asked: he not only infiltrates the tournament and secures evidence of the sex-and-heroin trafficking business, but he also dispatches O’Hara, beats the hell out of dozens of lackeys, and kills Mr. Han by kicking him onto a spear.

This is standard action movie stuff for modern audiences, a template that combines the geopolitical intrigue of James Bond with a shirtless physicality later copied by the likes of Stallone and Schwarzenegger. But unlike Bond there’s no love scene for Lee. The choreographed fighting is the love scene, or maybe the choreographed fighting is the dancing is the love scene. Pauline Kael compared Bruce Lee to Fred Astaire; I think the comparison works better with Rudolf Nureyev. Astaire had a besuited, playful grace, while Nureyev was shirtless, dramatic, and muscular. Astaire moved with athletic modesty, while Lee’s bravura dominated the screen.

This bravura is most evident in Enter the Dragon’s strangest sequence, when Lee fights O’Hara. Earlier in the movie, Lee learns that his sister’s death was O’Hara’s fault—the big bodyguard tried to rape her but she committed suicide before the act—and we expect Lee to get his revenge. Instead, he toys with O’Hara. He humiliates him before knocking him out. Revenge of a kind, not the revenge we’re expecting, maybe not even the revenge Lee was expecting, until O’Hara regains consciousness and tries to stab Lee with a broken bottle. Lee kicks him down, then leaps into the air and lands on O’Hara’s chest. We hear the crunch of bone and we get a slow-motion closeup of Lee’s face, whose mouth is now wide open in a scream. He seems horrified, confused, on the verge of tears. He seems to realize that although he got the revenge we were all expecting, his sister is still dead, which makes Lee the first, and possibly only, action star to suffer through an existential crisis in the midst of a fight.

A similar motif returns later in the movie, when Lee seizes one of Han’s many lackeys, played by a young Jackie Chan. Lee has the lackey by the hair, the camera zooms in tight on Lee’s face, and we expect a repeat performance: the slow-motion horror, the verge of tears, another existential crisis. But befitting the strangeness of the movie, this time Lee breaks the lackey’s neck with glee. The violence is swift. Lee’s expression is almost orgasmic—he likes to be watched.

Steve McQueen was one of Bruce Lee’s kung-fu students. Bruce wanted to make a movie with him, but he said no. Steve McQueen could be boring in his performances, his laconic charm often descending into half-lidded disengagement, but he understood how to seduce. Unlike Lee, McQueen gave the illusion of physicality while not moving at all – his most abiding action sequence has him driving a car.

Contrast McQueen’s acting strategy with Lee’s earlier work in those mediocre Hong Kong productions. Before Enter the Dragon, Bruce was a nascent sex symbol, not yet cool, still trying to convince the audience that he was worthy of their attention. His performances were corny, exaggerated in that classic Hong Kong theatrical style. McQueen showed Lee how to make the audience into the voyeur. All film icons like to be watched but the best ones are able to conceal that fact.

In the words of Matthew Polly, author of “Bruce Lee: A Life:”:

“McQueen taught Bruce how to be cool. Bruce was already pretty cool – cool for Hong Kong or Seattle – but McQueen took him to Hollywood-level cool. It is one of the reasons why when Bruce went back to Hong Kong, he blew people away, because he had a strut they had never seen before.”

McQueen’s influence is there but Bruce made it his own. Bruce didn’t succeed as an actor because of McQueen – he absorbed what was useful and discarded what wasn’t. He took the coolness and contrasted it with intensity, a flash of his own vulnerability, and gave it dynamic range. Bruce is a better actor than McQueen. We see Bruce’s artistic maturation occur in real-time, during Enter the Dragon. He begins as that Chinese-American actor stuck in mediocre Hong Kong productions and emerges as the coolest sex symbol audiences had ever seen, maybe one of the better dancers, certainly a bedroom fantasy who transcended stereotype.

Fifty years is ancient in cinematic terms but icons exist outside of time. They are immortal, forever waiting to be watched. Watch Enter the Dragon and witness Bruce Lee’s maturation. Watch him become the biggest action star in the world, in a poorly-shot kung-fu flick where the hero survives a big bodyguard, dozens of lackeys, and an existential crisis. Watch him join the list of Hollywood’s iconic sex symbols. Bruce Lee the person died fifty years ago; Bruce Lee the actor remains very much alive.

Published 17 Jul 2023

By Anton Bitel

King Hu’s seminal ’70s wuxia is finally arriving on Blu-ray and DVD later this month.

By Anton Bitel

Sammo Hung stars as a hapless amateur detective in Wu Ma's classic comedy caper.

By Anton Bitel

Like its predecessors, 1992’s Police Story 3: Supercop offers plenty of thrills and spills – but with more political commentary.