When Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike first erupted gloriously onto screens, reviews appeared that couldn’t help but be seen as stained by internalised misogyny. Whilst currently holding a 78% Rotten Tomatoes approval rating, some ‘rotten’ reviews described it as being a “guilty pleasure for sexually frustrated housewives” and that “on the scale of chick flicks, Magic Mike is a 10”.

Terminology rooted in misogyny like ‘chick flick’ and ‘housewives’ attempts to devalue Magic Mike, a film firmly engaged with the flaws with the American dream. Such terms are predominantly only used when attempting to trivialise films marketed towards queer and female audiences, so when Magic Mike XXL dropped to similarly misogynistic reviews, there was a certain irony to be had, as Gregory Jacobs’ playful sequel focuses on denouncing the repressive nature of toxic masculinity and celebrating its queer and female target audience.

Toxic Masculinity, or ‘traditional masculine ideology’, is the idea that men are unable to express themselves emotionally for fear of appearing ‘weak’ or ‘feminine’. In Magic Mike XXL, this manifests itself early on when Mike Lane (Channing Tatum) is told by Tarzan (Kevin Nash) that their former boss has ‘gone’. Tarzan – aptly named, as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ protagonist is a traditionally toxic male archetype that abandons culture and emotional intelligence – obscures the vulnerability he would feel by admitting that he and the “Kings of Tampa” have been abandoned by their shady figurehead Dallas (Matthew McConaughey), choosing instead to let Mike believe Dallas had died.

Having chosen the capitalistic ‘American Dream’ at the end of Magic Mike, Mike doesn’t initially join back up with the group on their pilgrimage to Myrtle Beach. That is, until Ginuwine’s ‘Pony’, a song he once danced to in his routine, comes on the radio. He begins dancing erotically in his workshop, his gyrating hips and phallic-replacement drill thrusting, reminding him of a former career he was passionate about. The moment allows the audience, and crucially Mike himself, an insight into his current life: he’s no longer free to be the sexually liberated person he used to be, who took pride in his work of providing pleasure to women.

Mike, seeking a modicum of his former happiness, joins back up with the posse of Adonises, much to the chagrin of Ken (Matt Bomer) who feels that Mike abandoned them and is yet to apologise. A traditionally toxic idea surrounding male conflict is that violence solves problems – how often within mainstream media are audiences forced to witness two men go toe-to-toe, their easily solved conflict devolving into fisticuffs, their fists doing the talking? Magic Mike XXL features a single bout of this kind of violence, phrased as “old-school therapy”.

It plays out in a cliché fashion, the men loudly goading each other with insults. How the scene ends, however, is what shows writer Carolin’s true intention: Mike, after being punched by Ken, asks “Do you feel better now?” Ken replies “No I don’t…that was seriously f*cked up. There are a lot better ways to handle that shit.” While the men initially laugh his reaction off, it reverberates through the film as every single conflict from this moment on is handled through dialogue, compromise and with emotional maturity. Jacobs uses the scene to deplore the unmerited anger that men so often feel they must peacock, to tell men that violence is not the answer.

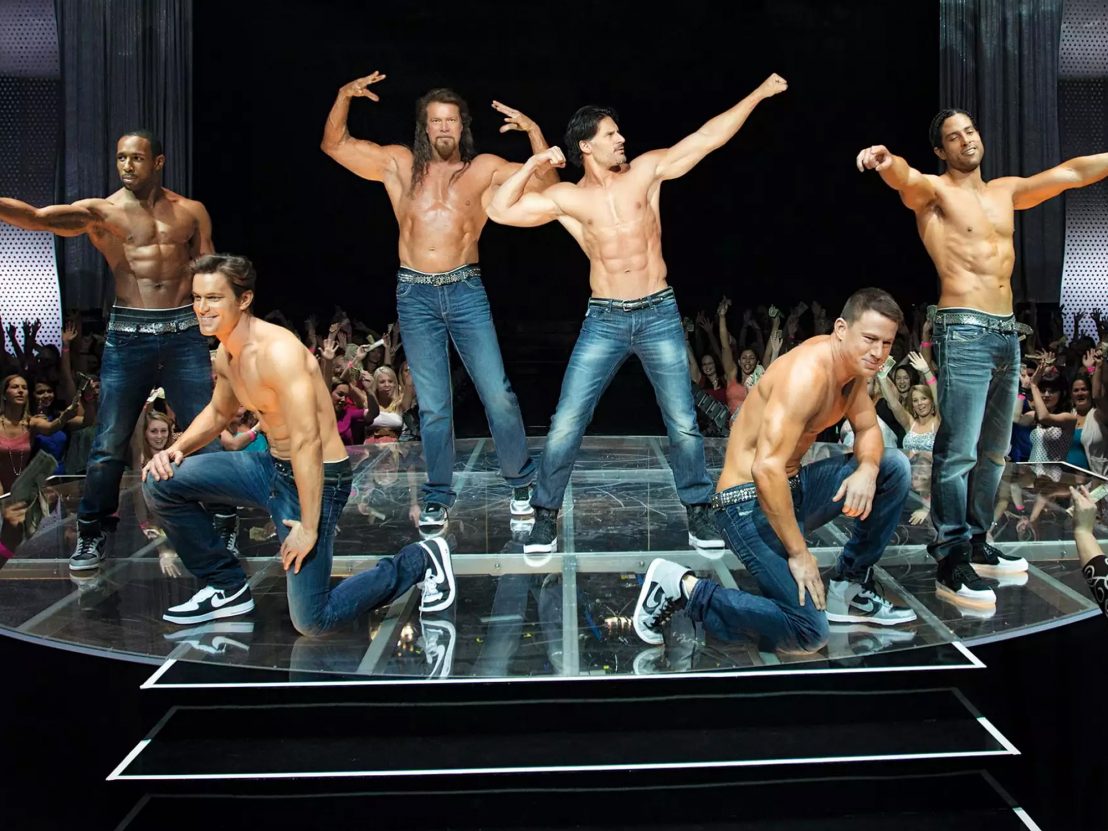

It’s symptomatic of toxic masculinity to avoid emotional vulnerability, and Magic Mike XXL chooses to smash the notion that vulnerability equals weakness by portraying a group of conventionally attractive men with both emotional depth and ability beyond what capitalism dictates. With a subtle focus on the arts, our stripper protagonists go through a metamorphosis, shedding the confining chrysalis of masculinity as the stereotypical blue-collar stripper costumes get discarded.

For their last hurrah, they choose to showcase not just physique but complex maturity around their true passions. They’re finally honest with themselves, incorporating these wants into their routine. Ken wants to sing, Tito (Adam Rodriguez) wants to make probiotic fro-yo, Tarzan wants to paint – with glitter! – and Richie (Joe Manganiello) wants to settle down, dancing to Bruno Mars’ ‘Marry You” while worshipping a woman in a bridal veil. There’s even a subversion of stereotypical heteronormative marriage as it transforms into BDSM when he throws his pseudo-wife into a sex swing.

While Magic Mike XXL speaks progressively on [toxic] masculinity, an element that truly stands out is the film’s astute take on female empowerment. Women, of varied races and sizes are deemed queens and are all consensually invited on stage or into a chair and worshipped. When the strippers need assistance, they turn to Rome (Jada Pinkett-Smith), a woman who taught Mike everything he knows, replacing the McConaughey emcee – the role was originally written for Jamie Foxx, but it’s infinitely more fitting that a woman is the one who holds all the cards for Mike and the gang, reframing the power balance.

This is also seen in Richie and Nancy (Andie MacDowell)’s blossoming romance, which is handled with a rarely seen sensitivity. Nancy, who is in her late 50s, broadcasts to the group that she wished she had “known you guys back in our day”. Richie quickly shoots the idea down, telling her that ‘It’s still your day, ma’am”. After they’re intimate, the group – instead of glorifying Richie’s having had sex – they congratulate him on finding a connection with a beautiful woman. Nothing is more indicative of this subversive mentality around female empowerment than when Andre (Donald Glover) who joins the group at the behest of Rome, says that men don’t listen to women, and that “all we got to do is ask them what they want and when they tell you, it’s a beautiful thing”, going on to emphasise that they can be healers, if men were to take the subversive lessons of Magic Mike XXL on board.

Magic Mike XXL progressively incorporates ideas around the fallacy of masculinity, portraying toxic male attitudes as a symptom of capitalist structures and deconstructing the notion that female sexuality and desire is shameful. The strippers in Magic Mike XXL aren’t just removing their clothes for the visual pleasure of others – by the end they’re stripping away at the patriarchy and societal systems that allowed toxic masculinity to take root.

Published 8 Feb 2023

Channing Tatum leads a troupe of sensitive male strippers in this explosively sexy road trip movie.

Steven Soderbergh directs the third installment of the male-stripping saga as Mike brings his talents to London.

Channing Tatum and co’s triumphant return is an endorsement for sexual empowerment, not exploitation.