Thirty years after its release, Beetlejuice remains an imaginative exception in the dull landscape of mainstream cinema. Based on a macabre story concept by screenwriter Michael McDowell, the original script envisioned a happily married couple suffering a horrific car accident only to be terrorised by a winged demon creature. Tim Burton’s interest was piqued and after a rewrite by Warren Skaaren, the film became a lot funnier, focusing more on the bizarre bureaucratic world of the afterlife. With the director bringing his own B-movie aesthetic to the project, Beetlejuice became an instant fan favourite.

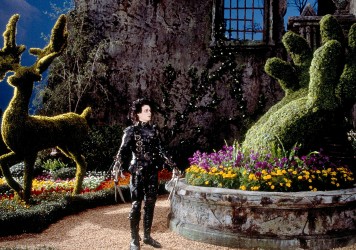

Relying on old-school moviemaking craft, Burton took full advantage of Beetlejuice’s limited VFX budget (just $1 million) to create a lo-fi, animated production design. Like a cross between Ray Harryhausen and Chuck Jones, this world has colour, texture and weight. Drawing on the opening sequence featuring a model-scale of the town, the entire film evokes a kind of Toyland where the characters are at the mercy of a hierarchy of supernatural forces, like dolls in a child’s playhouse.

Without delving too deeply into the tragedy of death, the film translates the sheer helplessness of grief with aplomb. Capturing an almost Hellenic interpretation of the afterlife, death might unlock untold potential and does mean a certain immortality, but compared to the richness and pleasure of living it is severely lacking. Transforming the underworld into a green and purple waiting office, Burton balances his idiosyncratic, vibrant visual style with an almost overwhelming sense of dread. While certainly not the first filmmaker to express the horrific emptiness of an endless void as an inefficient bureaucracy, it is remarkably effective as a comedic anchor.

Further playing into the idea of the film as a large playhouse, Winona Ryder steps in as a kind of Goth Barbie. While no means a flat character, her Lydia serves as a kind of fantasy figure for young people who wanted to be Elvira and not Sandra Dee. With jet-black hair and pale skin, she has a wide array of petticoats, jewelry and vampire-inspired clothing that never fails to make the teenage girl in me swoon. More than just a grumpy adolescent, Lydia is presented as a creative spirit stifled by selfish parents who give her no attention and pressure her to be “normal.” Moving into the film’s third act, unlike her profiteering parents, she is willing to sacrifice her immortal soul for her new ghost friends.

Along with Labyrinth, Beetlejuice fits into a small sub-section of 1980s cinema where a teen girl is betrothed to an overtly sexualised fantasy creature. Partially a kind of dizzying coming of age fantasy, the sexualised aspect lends a sense of real danger. Playing off a romanticised vision of death, one that Lydia harbours, the film also serves as a deeper allegory on our obsessive and perhaps unhealthy need to shelter our children from natural aspects of life, namely, sex and death. Lydia, left to her own devices, has to seek parental guidance from a recently deceased couple because her sense of isolation has led her to consider refuge in death.

Beetlejuice himself, played by a deliriously horny and charming Michael Keaton, is a perfect trickster incarnation. Building on one of storytelling’s oldest trope, Burton and his writing team craft a sleazy and untrustworthy character who still convincingly provides a solution under desperate circumstances. Keaton gives a tour-de-force performance as the gravelly-voiced demon who wants to be unleashed on the world to indulge in a self-gratifying pursuit of pleasure. Not quite malicious but definitely lacking in empathy, Beetlejuice is the ultimate party animal, willing to throw all common sense out the window in pursuit of a good time.

At the time Beetlejuice was made, Burton seemed like the heir apparent to Frank Tashlin, the innovative Warner Brothers cartoonist who translated his pop-animated style to some of the best films of the 1950s, including Artists & Models, The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. The film’s vibrant aesthetic, matched with Danny Elfman’s rollercoaster score and Harry Belafonte’s original island music, blends the extremes of pleasure, play and death, in a comedically tense afterlife adventure.

Burton has long since worn out his welcome as an alternative voice in the world of mainstream cinema. Just as he found wider commercial success and began to be taken seriously, his films became increasingly bogged down by glossy special effects. Watching Beetlejuice today is a reminder both of Burton’s once boundless potential, and of the increasing void left by the absence of hand-crafted practical effects.

Published 24 Oct 2018

By Taryn McCabe

So much about this cult fantasy endures, from its use of practical effects to David Bowie’s captivating performance.

The master of the macabre hit his creative peak with this singular suburban fairy tale from 1990.

Many of the director’s trademarks can be seen in his 1982 adaptation of the classic Grimms’ fairy tale.