Unclassifiable docu-fiction hybrid Gray House is the hot ticket at New York’s Lincoln Center this week, where it screens as part of the Art of the Reel festival. The event’s website gives a clue as to why: “Austin Lynch (son of David) and Matthew Booth candidly explore the American working class through a stunningly photographed weave of verité footage, interviews, landscapes, and fictional elements.”

But while there’s seldom such thing as bad publicity, having sat down with Lynch in Copenhagen recently – where his film received its world premiere in competition at CPH:DOX – it’s hard to imagine he’s particularly thrilled by such prominence being accorded to his famous father’s name.

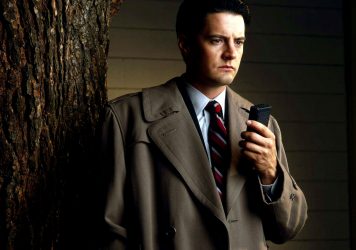

In person Lynch Jr, who sometimes goes by “Austin Jack Lynch”, sometimes simply “Austin Jack”, is earnestly amiable, dark-haired and -bearded, solemnly handsome in a vaguely Jake Gyllenhaal-ish way. In broaching the subject of illustrious kin via a follow-up email – and being aware that Lynch’s parents separated around the time he was born (while David was working on Dune) – I decided to mention his aunt, Sissy Spacek, production designer uncle, Jack Fisk, and director sister, Jennifer.

His response was polite but firm: “For the most part, I have to say that I am very hesitant to get into all of these questions regarding family connections and influences. Please don’t take this the wrong way. It’s just that the film is so far from all of this that it feels besides the point, and, I fear, directs attention away from what’s important. It’s also, very simply, not how I would like to contextualise the work.”

Fair enough. And while it’s tempting to identify “Lynchian” flourishes in Gray House’s moody visuals, the film – officially directed by Lynch but presented as “a film by” Lynch and acclaimed Canadian photographer Matthew Booth – is very much its own beast. A five-part meditation on solitude and isolation bookended by powerful sections “starring” French actors Denis Lavant (Holy Motors) and Aurore Clément (Apocalypse Now),

This distinction was recognised by the CPH:DOX jury, who gave Gray House a special mention “for its astonishing use of cinematic language to create a profound sense of human isolation.” The citation is a small but crucial step in 34-year-old Lynch’s steady emergence from his dad’s long shadow (his previous credits include making of documentaries on Terrence Malick’s The New World and Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood.)

Having appeared in small roles in both Twin Peaks (as ‘little boy’ in a 1990 episode) and Inland Empire (as a driver), Austin had greater involvement on David Lynch’s Interview Project – an experience which stood him in good stead when it came to Gray House’s two relatively straightforward documentary segments. These take the viewer into an oil camp in North Dakota (where we hear from blue-collar male workers) and a prison in Oregon (female prisoners). The straight-to-camera dialogue is accompanied throughout by an eerie, low-key soundtrack.

This slightly unsettling use of score isn’t the only offbeat aspect of Gray House, which positions the interview sections as parts two and four. Parts one, three and five are examples of slow-cinema fiction set in Texas (where Lavant plays a taciturn riverboat fisherman), Virginia (an alluringly lazy interlude featuring artist Dianna Molzan) and California (where we observe Clément’s character alone in her opulent, desert-side residence.)

Given Booth’s background in photography, and Lynch’s in painting, was Gray House always intended to be a film, or could it work in an installation-type setting? “I think we’ve been resistant to that all along,” says Lynch, “because it separates it from being an immersive cinematic experience. It was certainly made for the cinema screen; our thinking was always about how you would experience it in that environment, seen from start to finish, in a dark room, with good sound and good visuals. Everything we did was with the idea of it being viewed in that space, and it’s important that it should be seen as a whole work.”

“We both have these connections to the art world,” notes Booth, “and I can imagine an art audience having a possibly different reaction to it than the film community. In a gallery they can arrive in the middle, decide if they want to keep watching, or move on and see something else, rather than coming at the start and being a ‘captive’ of the film.”

Despite the vague description of the film offered by CPH:DOX, which is likely to leave audiences unprepared for the unusual demands of the film, Lynch says that he fully embraces ambiguity. “It’s so important that the audience can enter the world of the film, because it’s our hope that it will offer an immersive experience. Film has a rhythm – many times you go in and see a film you’re not expecting and you don’t seep into its rhythm, especially works that have an unusual structure, or aren’t conventional narratives. So, how do you create a film that has its own internal rhythms and structure, and then just expect people to dip into it, coming from their normal lives, and day-to-day activities, to enter the cinema and become immersed?”

This aspect of Gray House makes the opening segment, which runs more than 10 minutes and features no dialogue, particularly crucial in terms of allowing the viewer to depressurise into a new kind of cinematic zone. “That sequence was always intended as an opportunity for the viewer to slow down and enter the world of the film,” Lynch explains.

And once such an adjustment is made, what kind of reward do the filmmakers hope the film’s audience will receive? “It’s about looking deeper,” says Lynch, “through the crack into the egg, to explore matters rather than enforce particular binaries or contrasts. It’s not about comparison per se, it’s about composition – about making connections, opening it up.”

A crucial element in making such connections is the sound of the film. This is where Alan Splet, David Lynch’s legendary audio collaborator on Eraserhead, The Elephant Man and Dune, comes into play. Yet in analysing the soundscape of Gray House, Booth brings up Alvin Lucier, the octogenarian doyen of American experimental music whose compositions are notable in the Oregon section: “he uses sine wave oscillators, equipment like that, working a lot of the time in the very high frequencies… It felt appropriate, the way he uses structure and variation.”

In terms of collaborators in front of the camera, Lynch becomes particularly animated when discussing the involvement of Denis Lavant, who like Clément was cast “because of who he is on and off screen. It’s about Denis as this energy, this person, this identity. Everything he says sounds like the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard. One thing he said when I first met him was that every role he plays is like another layer he puts on, and he draws from all of his past roles in each new performance… I think that’s deeply connected to the way we’re working.”

Published 22 Apr 2017

By Ed Gibbs

The cult filmmaker shares stories and archive from his childhood, while still managing to remain as elusive as ever.

By Jack Godwin

From a severed Barbie head to Twin Peaks spin-offs, the director has made some truly bonkers ads over the years.

By Jack Godwin

Who’s back, who’s missing, and will we see more of the Red Room?