Carlos Cuarón, Writer/director: In 1997 I started directing short films I had written, and in 2000 I was going to make my first feature but the production collapsed. In hindsight I’m grateful, because I wasn’t ready to direct it – the script wasn’t ready; the producers weren’t ready. Ad because of that, I sat down with Alfonso and wrote Y tu mamá también.

Alfonso Cuarón, Director: My son was in New York and we’d go to movies together all the time; sometimes I would choose the movie, and other times he would. And basically I had to see a lot of crap, and a lot of teen comedies. The problem with the teen comedies is that there’s something really interesting at their core: they’re so moralistic and they have a phoney and overly respectful sense of character. You don’t have to make fun of the characters or invent clever plots to humiliate one or the other, or have them sticking their dicks into a pie. I was lucky, because when my son was ten I made A Little Princess, which, in a way, was a film for me; and then I wanted to do a teen movie for him because of course he ended up being a teen.

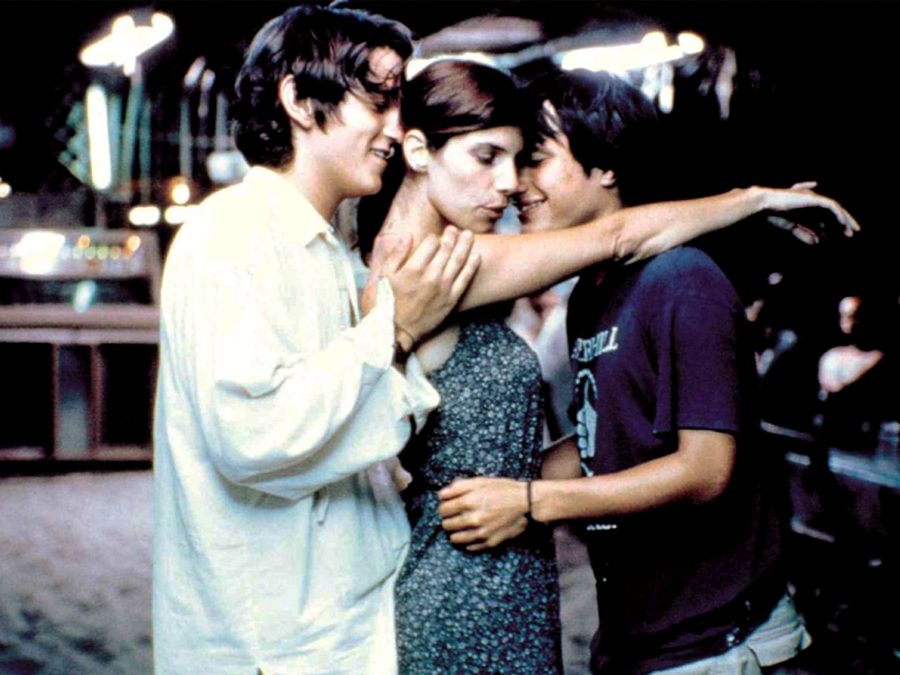

This movie was Y tu mamá and in many ways I used my son as an adviser. Ultimately my son is very Mexican – even living in New York he’s very Mexican and he sees that the fundamentals and the emotions between teens – most of his friends are American – are basically the same. The politics may be different but the human experience is ultimately the same, they are all insecure, they all want to bed women and they are all in love with the girl who loves the other guy.

Carlos and I had talked about the ideas of Y tu mamá even before Sólo con tu pareja. We were looking for a low-budget film to do before my first film. Lubezki suggested a road trip to the beach, and Carlos loved the idea of two boys and one girl. For various reasons we moved on into Sólo con tu pareja. But, every couple of years, Carlos and I would return to it before putting it back in the drawer. It was in this way that it evolved.

Directors are really perhaps only as good as the projects they choose. And choices can be dangerous, because you can lose sight of what you really want to do. What happened to me was that I was choosing so many projects that I forgot that I could write. And that was part of the beauty of Y tu mamá.

Emmanuel Lubezki, Cinematographer: I remember when Alfonso and I were working on Great Expectations and we were both so fed up and having trouble finding the energy and enthusiasm to like our work any more. We both felt that Y tu mamá también was a way of reinventing ourselves.

Guillermo del Toro, Director: I think that a career is a learning curve. Alfonso and I have discussed this many times. I remember Alfonso being revered as a visionary when A Little Princess came out and maligned as a hack when Great Expectations emerged. I went through similar stuff with Cronos and Mimic, and I said to Alfonso, ‘People seem to think that you are making a definitive last statement with every movie. It’s not the case; you are searching, in the way that a painter may experiment with a blue period or a green period.

Alfonso Cuarón: I didn’t do Y tu mamá to go ‘back home’; I did the film in Mexico because I always wanted to make it. I never really intended to go to Hollywood, and I don’t regard it as the Mecca of cinema. For many directors, Mexican or otherwise, it’s a goal; for some others it is just part of a journey. For me, personally, it’s the latter. I want to do films elsewhere and everywhere.

Some filmmakers don’t need to touch Hollywood. Guillermo del Toro is clear: when he does his Hollywood movies, he isn’t pretending to do his smaller movies, and vice versa; they are two different approaches and two different beasts.

When I did Y tu mamá I did feel that I had perhaps started to lose some of my identity and that I needed to reconnect with my roots – not bullshit nationalistic roots but creative roots. I wanted to make the film I was going to make before I went to film school, and that was always going to be a film in Spanish, and a road movie involving a journey to the beach. All the rest, Mexico versus the big Hollywood giants, is ideology. I have very eclectic tastes in terms of film, and I want to explore these.

Great Expectations, if it was successful or not is not for me to say, but it’s obviously a completely different film to Y tu mamá; it has an entirely different point of view. The same with A Little Princess – I was following the point of view of the main character. Our approach, mine and Lubezki’s, on these films was not to see the world the way it is, but the way it is perceived by the protagonists – to give a heightened reality, almost. On Y tu mamá we wanted to do the opposite: an objective approach to our reality, just to keep our distance and observe things happening.

Carlos and I didn’t find a way into the film until around 2000, when we decided that the context was as important as character and that we wanted a very objective and in some ways distant approach to the story. We didn’t want to take a nostalgic approach.

Carlos Cuarón: We were kind of blocked in the writing and got ourselves stuck with a narrator. He doesn’t actually narrate that much; rather, he contextualizes. And we decided that context – in this case, Mexico, as a country – was character. When we discovered this early structuring, we decided that it was a parallel trip. The woman’s journey is also important, because she too is finding her own identity, perhaps in a much more Spanish way. But, yeah, the two guys are searching for an identity. And I still feel that Mexico is still a teenage society. The difference, I believe, is that the society is much more mature than the government. We are sixteen, seventeen, and pimply and in the middle of the teenage years. And my feeling is that the government is about thirteen and just starting with the hormonal thing…

Emmanuel Lubezki: It couldn’t be just a coming-of-age story and nothing else. The context is so important, and it’s actually a very complex movie told in quite a simple way – that’s what really blew me away. A friend of us who lived with us in Mexico when we were growing up but then moved back to Uruguay wrote to me to say that the film really helped him understand who we were, and how sex was so important to us that, despite our leftist sympathies, it blinded us to the situations that were going on around us. Sadly, Mexico is now such a complex country that if you and a girl were to head to the interstate in a car the chances are that you would be robbed and raped.

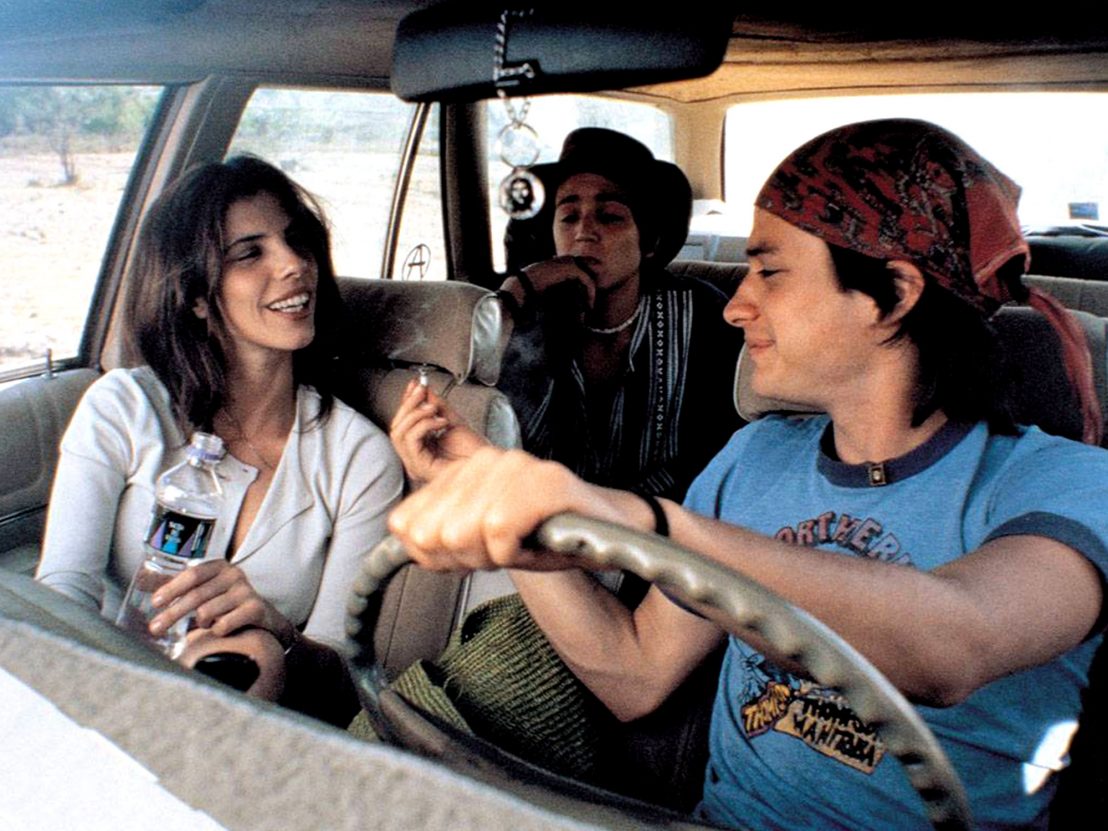

Alfonso Cuarón: The story wasn’t autobiographical, but there are elements from when Carlos and I were growing up. The nanny in the film is played by our nanny in real life, and one of the destinations the trio go through is her town in real life; Carlos and I went to a wedding in the same place where you see the wedding in the film, and the President of the time was present and everybody was more interested in the President than the newlyweds. We also had a car like the one in the film and there is a town the trio visit that is also the name of the street where we grew up.

The character of Diego ‘Saba’ Madero, the friend of Julio and Tenoch, is a character that we know. Of course, we both also had trips to the beach and the incident with the pigs in the tent happened to my cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki. There’s lots of incidental stuff like that. I think that both Carlos and I are in between Julio and Tenoch – leaning more towards Julio, I guess, socially speaking. What we really wanted to do was convey a universe and an atmosphere that we really knew first hand.

Carlos Cuarón: It was mainly drawn upon our energy as teenagers and the adolescence I had. It’s not autobiographical, except for the scene where Diego questions Gael about how he fucked his girlfriend in the hotel. This actually happened to me when I was playing for a football team, and it involved someone who was then a very close friend. It wasn’t difficult for me to write this scene, because I already had the dialogue. There are specific things that only very close people would know. For example, our family had a car with the same name as that in the film,2 and our mother in Mexico City lives in a street after which we named a town in the film.

Emmanuel Lubezki: I was so happy when I read it – because it was so close to us and to our lives. It was a story that we had talked about for many years, mainly while getting drunk in bars while eulogizing our love of road movies. We would talk about this crazy idea of a road movie with two guys and a girl. To then suddenly see all this stuff written down by Alfonso and his brother Carlos was amazing. The film offered portraits of people that we know and captured them so well. I immediately told them that I had to shoot the movie.

Gael García Bernal, Actor: I think that this film has a real edge to it and also a lot of depth. I also have to say that I think it’s the best script I’ve ever read. I was laughing from the first paragraph, and really enjoying it so much. The characters and the situations were so alive but also full of subtleties. The depth of the film is perhaps surprising, because it really comes from a very clichéd story. I mean, two guys taking a road trip with a woman – how B-movie is that? It’s Porky’s meets Dude, Where’s my Car? But Y tu mamá had a genuine reason to exist and a connection to real kids who were experiencing the loss of innocence.

Emmanuel Lubezki: It was also important, and perhaps not unconnected, that the film was independently financed. One of the reasons that film was slow to evolve in Mexico was that the directors had to wait for the government to fund them. I have to say that through a combination of luck, charm – he is the most charming – and judgement, he met Jorge Vergara. Now Jorge is hooked on movies. I had dinner with him last week and he told me he was fucked. I asked him why and he said, ‘Because I love making movies so much.’

Alfonso Cuarón: In Julio’s room there’s a poster for Harold and Maude (1971). I wanted to put Godard’s Masculin-Féminin (1966) in because that was the only conscious reference Carlos and I had when writing the script. But it’s probably for the best that the poster didn’t arrive. Character-wise Harold and Maude probably has more to do with my film in terms of the relationship between male and female. It’s also a beautiful film.

Carlos Cuarón: Alfonso and I wanted to make a very realistic movie that would be like a candid camera. Chilango, generically speaking, is what we use in Mexico City. It’s the language that all Chilangos and all Mexicans would understand. What we did, and what is original, is that we used hardcore Chilango, and you rarely see this in movies. You see it more maybe now as it’s become slightly standardized. In Amores Perros they also speak Chilango but it’s not hardcore Chilango. We were the first to do it with that freedom, that freshness if you will, and it played very well.

Emmanuel Lubezki: I love the fact that the style that we found to shoot in really suited the movie. When we started work, we weren’t cutting and we were shooting without covering, which is quite a risky thing to do. I remember Alejandro González Iñárritu coming to the set and telling us that we were insane, that we were ruining the rhythm of our movie because we didn’t have anywhere to go. Because he’s our friend and because we rate his work, we panicked – for one night. Then we watched what we had shot, and decided it was still the way that we were going to do it. And I really think that this was the best way to tell the story.

The entire movie is shot hand-held. This all goes back to our original idea of fifteen years ago, in which we would do a low-budget road movie that would allow us to go with some young actors and semi-improvise scenes and have a bare storyline but not be afraid of adding things as we went. We also wanted to work with a lot less equipment, because we felt that the last two movies we had done together in Hollywood before this one had both had a little bit too much. Everything was so slow because everyone was trying to make their work the best possible and everything was so expensive and there was a crew of something like a hundred and thirty people and this can really rob the project of momentum. This also robs you of the liberty to experiment. By consciously making Y tu mamá smaller and by working in a cappella fashion we could move faster and really let the actors go.

In its entirety it is the movie that I am most proud of, full-stop. I see other movies that I have shot and I often like moments from them but I have never liked a whole movie, except for this one. I love the story, I love the actors and I love the surroundings.

This extract was taken from The Faber Book of Mexican Cinema by Jason Wood, which is now available to order at faber.co.uk

Published 3 Jun 2021

By Luís Azevedo

In a new video essay, Luís Azevedo takes us on a journey through the Mexican filmmaker’s colourful worlds.

The Mexican writer/director describes coming home to make Roma, his most profoundly personal film to date.

The Mexican director’s early Spanish-language films offer vital dissections of the male ego.