Chris Bailey (Dave Cooper) walks in on Lance Boyle (Lucien Morgan) and Brenda Bristols (Linzi Drew) while they are having sex in their bedroom. As naked as they are, Chris asks angrily, “What are you doing here? You promised never to do this kind of thing again!” When Lance protests, “I never promised you any such thing,” Chris replies, “Not you, you twit – ’er!”, at which point Brenda insists, “I’ve never seen you before in my life.”

Realising with embarrassment that he is in the wrong apartment, Chris meekly apologies and leaves. Later, while Lance enjoys a post-coital nap, the still naked Brenda picks up the telephone ringing beside the bed and says, “Hello? No I’m sorry. No, nobody of that name. Okay, thank you, bye.”

These scenes are from an adult movie called See You Next Wednesday – a phrase that recurs as a sort of running in-joke in all of John Landis’ films. Here, See You Next Wednesday is a film-within-a-film, playing in the Piccadilly Circus porn cinema that David Kessler (David Naughton) visits near the end of An American Werewolf in London to confront the grotesque ghosts of all those he has inadvertently killed during the course of the film.

It is also a mise en abyme of the film that contains it. For See You Next Wednesday adds surreal humour to genuine softcore in much the same way that Landis’ film tempers real horror with lots of comedy – and the focus of these absurd snatches of dialogue on mistaken identities and wrong numbers picks up on a broader theme in An American Werewolf in London, whether it is the confusion of human and animal, or the accidental connection made between two related but nonetheless distinctive nationalities.

This is all in the title: for before Landis’ film has even started we already know not only that lycanthropy will be playing a prominent part, but also that this is to be a fish-out-of-water story, with American and English cultures forming a picture together that will quite possibly prove monstrous. The cultural hybridisation starts early, as David and his friend Jack Goodman (Griffin Dunne), two young New York Jews on a three-month back-packing tour of Europe, have ended up in rural Yorkshire. But when they seek refuge from the cold and rain in the pub The Slaughtered Lamb, they might as well, for the way that the locals clearly don’t take kindly to strangers around these parts, be entering a saloon in a classic American oater.

Indeed, films are very much a part of the conversational landscape too: when David jokingly suggests that the pentagram on the pub’s wall is a sign that ‘maybe the owners are from Texas’, and Jack tells the barmaid (Lila Kaye) to “remember the Alamo”, she thinks he is trying to get her to recall the time that she saw John Wayne’s The Alamo in Leicester Square (“Everybody dies in it,” as Jack comments on Wayne’s film, in another mise en abyme, “Very bloody”). Even the pentagram is related to a film, as Jack tells David, “Lon Chaney Jr in Universal Studios maintained that’s the mark of the Wolfman.”

In all this bar chat, we can see lines and purposes being crossed – just like in the later dialogue from See You Next Wednesday – as Jack and David struggle to find warmth, comfort and welcome in a place where they are marked as outsiders. The tension inside relaxes only when one of the drinkers (Brian Glover) tells a joke about a contingency from ‘the United Nations’ – a Frenchman, an American and an Englishman – travelling together. The joke is an expression of cultural commonality, even if its punchline shifts the focus back to American difference, indeed exceptionalism. And so that joke too might be thought of as reflecting the dynamics of a film in which an American, alienated by both his national and religious identity, must transform in an imperfect effort to fit in.

After Jack has been killed by a beast on the moors, the injured David is transferred to a hospital in London, a more cosmopolitan, less insular environment where the American fits in rather better, and almost immediately attracts the attention of Nurse Alex Price (Jenny Agutter). She reads to him from, significantly, Mark Twain’s ‘A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court’ and, unlike the belligerent Yorkshire folk, welcomes this American into her home, where they form a union in the shower, and in bed, in a sequence that culminates with Alex conspicuously wearing David’s NYU t-shirt. In other words, as these two enjoy their own softcore scenes together, they take mutual pleasure in a relationship of healthy cross-cultural exchange.

Yet An American Werewolf in London is as much tragedy as love story – an idea encapsulated in Alex’s claim to find David “very attractive and a little bit sad.” David’s own sexual attraction to Alex is repeatedly intercut with his dreams of bestial assaults on her, whether perpetrated by himself or by a jump-scaring Nazi Other (the ultimate Jewish fear, especially when in Europe) – and while he might, in going down during sex, find a salutary way to ‘eat’ Alex, his physical metamorphoses into a werewolf make their affair positively dangerous if not impossible. “I love you,” are David’s last words to Alex, “You’ve got to stay away from me!” And with that, this brief Anglo-American rapprochement is over, replaced with a cool distance. Alex may love David, but she cannot ultimately be with him, except to witness his departure.

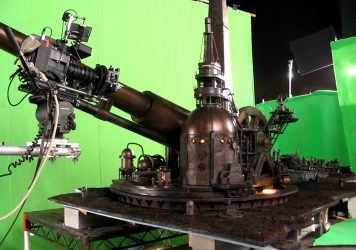

Much ink has (rightly) been spilt about the film’s extraordinary make-up and transformation effects (so impressive that a new Academy Award had to be invented for Rick Baker), about its killer soundtrack, about its perfect union of horror and comedy, and about its perfectly awkward merger of sex and nightmare. Yet David’s writhing discomfort in his own skin marks not just the monstrous metamorphosis in and of genre, but also that deep sense of estrangement experienced by any well-meaning if gauche tourist tripping up on local lore and mores.

Like a would-be stud in a skin flick entering all the wrong rooms or calling all the wrong numbers, David fails. We see him failing to get arrested by a bobby in Trafalgar Square, failing to connect – from an iconic red London phone booth – with his parents back home one last time, and even failing to kill himself, or to stop himself killing others. Such impotence may have no place in a porn film, but it is a familiar feeling for the foreigner – and even if David can find temporary shelter, solace and love in the arms of one English woman, he will nonetheless always be caught between two states and two cultures.

So An American Werewolf in London captures the tragicomic status of a stranger in a strange land – a figure who can often, without even realising it, trample over, if not downright butcher, local customs and conventions, and inspire aggressive lynch mob-like responses from the parochial populace. The irony is that Landis, who is himself, like David, an American and a Jew abroad, never puts a foot wrong. Perhaps, after all, a cinema (adult or otherwise) is the ideal forum where different cultures may meet and sort through their differences with good humour (and a bit of sadness).

An American Werewolf in London is released on Blu-ray by Arrow Films in a brand new 4K restoration from the original camera negative supervised by John Landis on 28 October.

Published 28 Oct 2019

The American actor’s reemergence in I Love Dick serves as a reminder of his rare talents.

By Anton Bitel

Joe Dante’s The Howling is a perfect blend of modern horror and practical effects.

By Lara C Cory

Old-fashioned techniques appear to have made a comeback, but the reality is they never went away.