Sogo Ishii’s Crazy Thunder Road begins with a smoking volcano, and a fallen motorbike. These opening images in fact come from the film’s chronological end, and between them one can discern the principal arc of its narrative, as the irrepressible eruption of protagonist Jin (Tatsuo Yamada) leads inevitably to his – and others’ – doom. To Jin, it is always better to go out in an explosive blaze of glory than merely to burn out, and so this feature embodies the very spirit of live fast, die young.

Insolent, recalcitrant Jin heads the ominously named ‘Kamikaze’ crew of the Maboroshi (or ‘Phantoms’) motorcycle gang, independently enacting vicious guerrilla attacks on other gangs. Yet the Mabaroshi’s leader Ken (Koji Nanjō) is straightening up his act and settling down with Noriko (Michiko Kitahara). “Guess I’m getting old,” Ken tells her, via outmoded intertitles which underline his obsolescence. In parallel to this serious new relationship, Ken is also entering an alliance with the other gangs. In other words, he is leaving behind childish things.

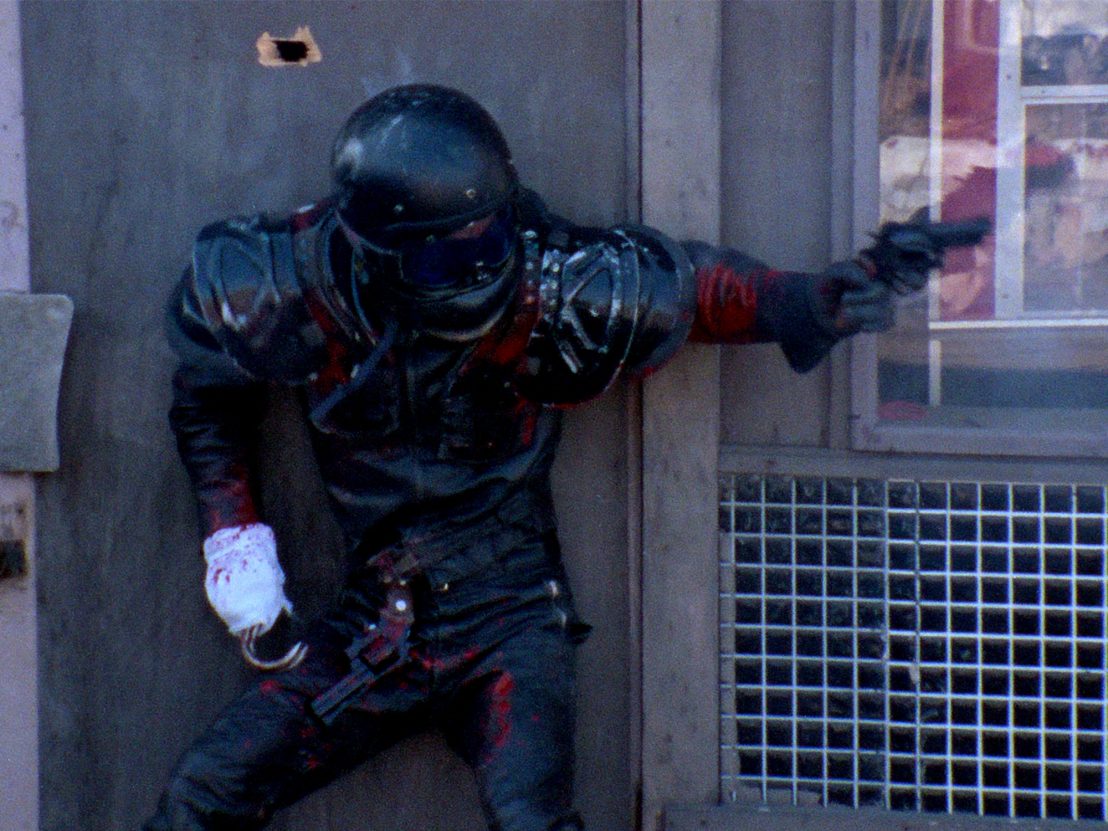

Jin, however, refuses to play ball or to acquiesce in any way to growing up, and so persuades the rest of the Kamikazes – and the conflicted Shigeru (Masashi Kojima) – to go rogue with him on a suicidal mission against, well, everyone else. With the stakes rising and consequences coming to call, Jin is left not only grievously injured but also increasingly isolated in his rebellious outbursts, even as all the other gangsters move on and grow up, either joining the police force or getting into bed (literally, in Shigeru’s case) with an ultra-nationalist paramilitary group led by the (significantly) older military veteran Tadashi (Hiroshi Kaiya).

When Jin takes his last ultraviolent stand, it is hardly a coincidence that he is joined in his heavily armed campaign by an actual child (albeit a street kid who sells drugs and injects heroin). For Jin is not only taking revenge against the many foes that he has made along the way, but also quixotically resisting the gravitational forces of adulthood itself. Sickened by the order and authoritarianism of grown-up life, Jin is a punkish Peter Pan taking one final chaotic ride under the banner of rebellious youth, and Crazy Thunder Road both celebrates and instantiates Jin’s unruly exuberance through Ishii’s kinetic, cut-up style of filmmaking.

Indeed, Jin and Ishii are driven by a similarly fierce independence. For much as Jin operates solo, beyond the control of the gang to which he belongs, and then of the military cadre that he joins merely to pick up fighting skills, Ishii himself was a practitioner of jishu eiga, or low-budget amateur films made entirely outside of the studio system. Shot for peanuts on 16mm, Crazy Thunder Road was Ishii’s film school graduation project at Nihon University, but extraordinarily was then picked up by Toei Studios, restruck on 35mm and released in cinemas. (The studio previously had Ishii’s no-budget first film, the 8mm short Panic in High School, remade as a feature in 1978.)

So Ishii, like Jin, was a free agent, working entirely autonomously at a young age, but still, again like Jin, attracting the attention of the big power players. Ishii was not however speeding down a road of crashing destruction, but laying the foundations for a long career in filmmaking which would include the futuristic dystopia Burst City, dysfunctional domestic drama The Crazy Family, remythologising period piece Gojoe and the cyberpunk Electric Dragon 80,000 V.

Crazy Thunder Road did not come from a vacuum. The aggressive anomie of its protagonist evokes (and updates) the bull-in-a-china-shop antihero of Kinji Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor, while the coded makeup and costumes of the different bike gangs are clearly influenced by George Miller’s Mad Max and Walter Hill’s The Warriors. This places Ishii’s film in a tradition of, precisely, non-traditional, anti-establishment works that kick hard against the status quo of a world that they expose as repellent, even fascistic in its conventions.

“Dedicated to all crazy bikers,” reads on-screen text at the film’s end, practically defying us to identify with its hero. As a wilful, pugnacious child in an adult’s body, Jin might not exactly be likeable, but his absolute refusal to bow or even compromise before oppressive authority makes him a figure of resistance and a volcanic force of nature, confronting our culture as much with electric brio as empty bravado.

Crazy Thunder Road is released on Blu-ray on 21 February via Third Window Films.

Published 21 Feb 2022

By Adam Cook

Nagisa Oshima’s 1968 film Death by Hanging is now available courtesy of The Criterion Collection.

By Anton Bitel

Kinji Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor and Takashi Miike’s 2002 update redefined the postwar Japanese gangster flick.

The ’90s straight-to-video boom reinvigorated the industry and made stars of directors like Takashi Miike.