We pay homage to director Clive Barker’s majestic suburban gore aria from 1987.

A promotional photo from around the time of Hellraiser’s release – its been over 30 years now since its early screenings at Cannes – shows director Clive Barker posing with his Panavision camera. He is a youthful thirtysomething, dimple chinned, sober of expression, and on the top of his right arm, which is draped over the camera’s focus ring, there is a gigantic snail. It’s a silly bit of ‘spooky’ business to distinguish the horror author du jour, but not altogether inappropriate – the movie that Barker was making would leave quite a slime trail behind it. Hellraiser has a particular texture; it’s grotty and soiled and a little abrasive, like synthetic stucco or pebbledash.

It’s one of those movies that you can instantly recognise from a single frame. Years back I caught a flash of some nondescript scene on a television at a heavy metal bar and I knew what it was right away, despite then not having seen the movie since adolescence – part of this, I think, has to do with that texture, part of it with the fact that Hellraiser is probably the movie you’re most likely to encounter playing on a TV in a heavy metal bar.

It is difficult to describe to anyone under the age of 25 the level of celebrity achieved by a small cache of horror writers in the 1980s. Barker was a household name, as was, for the grade school crowd, RL Stine, and of course both of them lived in the shadow of Stephen King, who never really went away. Before Barker signed on for Hellraiser, King had shown the way to expanding a franchise to multiplatinum delivery, not only licensing his novels for film adaptation faster than he could write them, but sometimes participating in the films themselves. King gives a grotesque, mugging performance as a gormless backwoodsman in 1982’s Creepshow, and handled directing duties himself, after a fashion, on 1986’s Maximum Overdrive.

Around the same time Barker was also making his way into features – he wrote the screenplays to 1985’s Underworld and 1986’s Rawhead Rex, both directed by George Pavlou. But his ambitions as a cineaste went back further than King’s. Born in Liverpool and raised near Penny Lane, Barker stayed in the city for university. He was by then pursuing an interest in theatre, particularly that of the transgressive variety, which would pick up the legacy of Paris’ Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol.

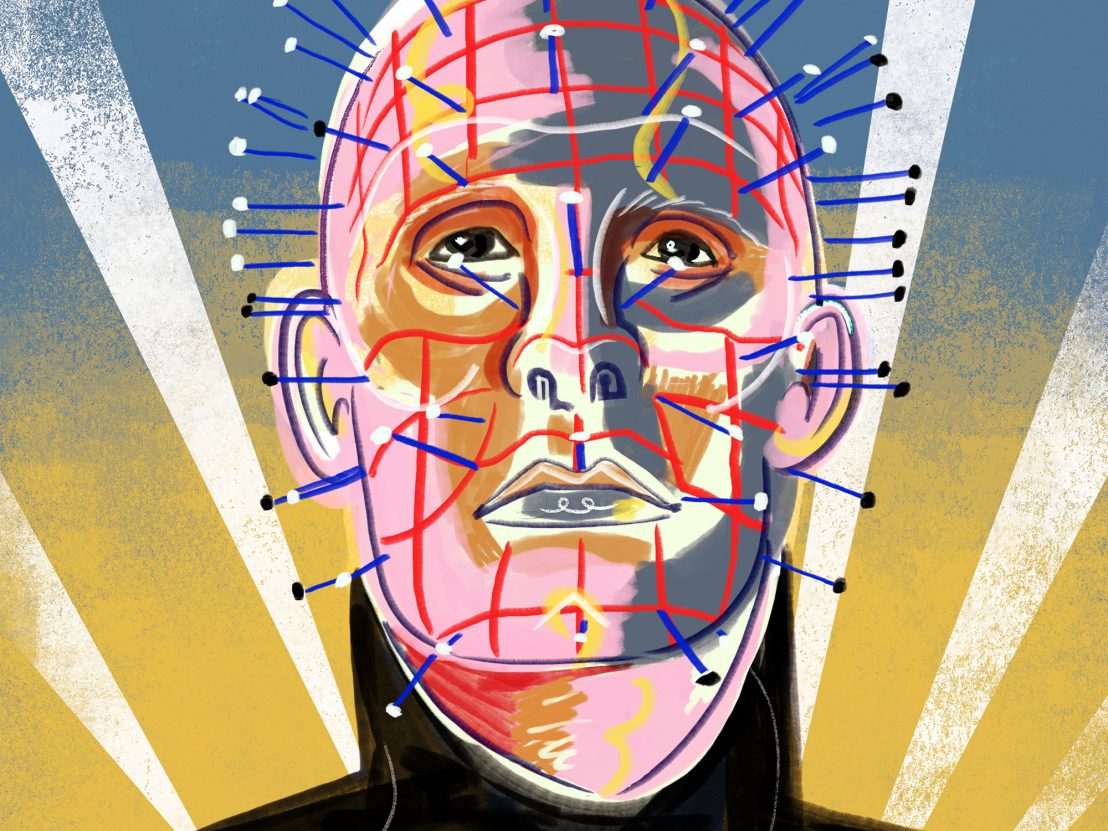

He would become a central player in a group of creative collaborators which included his pal from Quarry Bank High School, Doug Bradley, who would eventually star as Hellraiser’s dead-eyed breakout creature star, billed as “Lead Cenobite” in the credits but later affectionately nicknamed Pinhead. Barker’s troupe went through several incarnations, always with him at the core: The Hydra Theatre Company became the Theatre of the Imagination which in turn became the Mute Pantomime Theatre (Bradley recalls a production called ‘A Clowns’ Sodom’), and then finally, after Barker and Bradley had moved down to London, The Dog Company.

Concurrent with his work in “fringe” theatre, Barker was also trying his hand as a filmmaker, producing two non-synch sound shorts, Salome and The Forbidden, the latter of which introduced the image of a bed of nails pounded into a gridwork pattern. Neither Barker’s film experiments nor his theatre efforts nor his piecemeal work as an illustrator – he contributed one of the variations on John Entwistle’s mug to the cover of The Who’s ‘Face Dances’ – made him much of a living. But when the first of his ‘Books of Blood’ short story collections was a publishing phenomenon, he soon turned his hand to cranking out novels.

His second effort in that line, ‘The Hellbound Heart’, published at a slim 186 pages by Dark Harvest in 1986, concerns an amoral sybarite torn to shreds by interdimensional Cenobite demons after using a mystical puzzle box to access a plane of what is purported to be overwhelming sensory gratification. ‘The Hellbound Heart’ would form the basis of Hellraiser – though perhaps “basis” isn’t quite the word, as the timeline suggests that the book was very much written with the idea of a movie in mind.

Part of Barker’s stated motive for going back into movies was to prevent low-quality adaptations of his writing being made – he was vocally critical, for example, of Rawhead Rex. By 1986, Barker’s name was enough to command him a budget of just under $1 million from a post-Roger Corman New World Pictures as a first-time feature director shooting a movie absent of real stars. The nearest thing to one is Andrew Robinson, a Don Siegel favourite who appeared in Charlie Varrick and as the serial killer “Scorpio” in Dirty Harry.

Here he switches from nasties to play the ultimate fall guy cuckold, Larry, the clueless brother of the abovementioned pleasure-seeker, Frank (Sean Chapman). The circumstances of Frank’s disappearance are unknown to all but the viewer – we’ve seen him being julienned by the Cenobites in the film’s prologue. Larry moves back into the family abode in the company of his wife, Julia (Claire Higgins), a haughty ice queen whose preferred pastime is remembering the time that she allowed Frank to ravage her. As such, she’s overjoyed (and understandably a little taken aback) when a few drops of blood from a moving day accident bring Frank back to life – of a sort.

The resurrected Frank, far from the sexual athlete of memory, is a pus- smeared hunk of masticated gristle, sequestered in the house’s dingy attic. He will, he explains, need real blood sacrifices in order to fully reconstitute himself. Julia mulls over this moral quandary for all of a minute, but her burning loins carry the day, and soon she’s an old pro at luring podgy businessmen home from yuppie boîtes and leading them upstairs to smash their skulls in with a claw hammer. According to Barker, one of the ladies on the set suggested the lm should be titled, “What a Woman Will do for a Good Fuck.”

If there is a metaphor in all of this for, say, Britain under Thatcher, I fail to track it. In point of fact it’s never actually clear as to where Hellraiser is taking place – Larry makes reference to bringing his wife back to her home turf and Cotton speaks with an English accent, but scarcely anyone else in the movie does, and the London-born Chapman was dubbed in post production at the behest of the film’s backers. (In fact the exteriors for the house where most of the movie takes place were shot at 187 Dollis Hill Lane in northwest London; the interiors were done in Cricklewood.)

The dimension of social commentary, which eulogies to the late George A Romero are currently praising his movies for while entirely ignoring what really distinguished him as a filmmaker, is here almost entirely lacking, and the plot is at a minimum. Suspense is nominally supplied by Larry’s imperilment, and then by the threat posed to Larry’s daughter from a previous marriage, Kirsty (Ashley Laurence), who absconds with the puzzle box from Frank and tries to bargain with the Cenobites, promising to o er up her corrupted uncle, who has escaped their wrath, in exchange for her life.

“The Cenobites are a quartet of ghastlies in shiny black leatherette who skip from dimension to dimension practising fatal S&M.”

In absence of these qualities, Hellraiser focuses on devising images designed to induce a combination of wonderment and sheer, visceral disgust, from the various flayed Franks to the simple but effective scene of the meat of a human hand being ripped open by a rusty nail. Barker is an outspoken admirer of the Italian gore director Lucio Fulci, and in such moments, it shows. Horror is, like science fiction, a genre where the make-up effects person can be a matinee star, and Hellraiser elevated Bob Keen to something close to Tom Savini-level celebrity among the ‘Fangoria’ set.

It was Keen who helped create the different skinned Franks – played by actor Oliver Smith, chosen because he was enough of a weedy ectomorph to still appear stripped down beneath built-up layers of heavy makeup. The raw, gore-damp Frank recalls certain Florentine medical illustrations or Honoré Fragonard’s 18th century ‘écorchés’, prepared cadavers stripped of skin still on display at the museum that bears his name in Paris. The image of the skinned man is one that Barker had visited before in both The Forbidden and his 1981 play ‘Frankenstein in Love’, billed, as Hellraiser might have been, “A Grand Guignol Romance.”

Frank’s rebirth from beneath the attic oorboards is a sickening, stately set-piece, quite on a par with anything in David Cronenberg’s The Fly or John Carpenter’s The Thing, movies which pushed analog visual effects to the limits of their viscous possibilities. Barker and Keen’s other indelible creations were, of course, the Cenobites themselves, a quartet of ghastlies in shiny black leatherette who skip from dimension to dimension practising fatal S&M. They are led by Bradley, who had first played a somewhat similar judge, jury and executioner character called The Dutchman in Barker’s 1973 play Hunters in the Snow.

Some of Barker’s ideas didn’t come to fruition. He toned down Julia’s thirsty flashback, which plays slightly camp as is, from a freakier original, doing due diligence for the censors, who apparently saw nothing overly alarming about the film’s catalogue of methods for shredding and pulverising the human form. He’d wanted an original soundtrack from Coil, the electronic duo comprised of John Balance and former Throbbing Gristle member Peter Christopherson, a far from radio-friendly couple who’d released an album called ‘Scatology’ and trafficked in imagery rich with sexual deviance and body horror. (Hellraiser’s discourse with the visuals coming out of contemporary industrial music cannot be overstated.)

Instead he got Christopher Young, whose credits included Tobe Hooper’s Invaders from Mars and A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge – and in fact Young more than acquitted himself with his more traditional orchestral score, including the darkly roiling theme.

Despite these imposed compromises, including the disorienting non-specific city of the film’s setting – who could possibly think it was a liability to set a haunted house movie in England? – Hellraiser was a massive hit, making the stuff of hardcore kink subculture into a suburban Halloween costume. Barker, discussing his original conception of Pinhead, has mentioned the influence of Catholicism – Pinhead’s get-up suggests a combination of butcher’s smock and cassock; the nails driven into his face at even intervals, some strange ritual of penitence; and his bearing is that of an undead Torquemada.

Also influential was Barker’s predilection for BDSM – as a young man he contributed an illustration to the periodical ‘S&M’, the publication of which led to charges of obscenity against the magazine, and the author, who is openly gay, has been known to drop references to leather and muscle bars like Los Angeles’ Faultline into interviews. (Remembering the leather club scene in fellow Liverpudlian Terence Davies’ 1980 Madonna and Child, one wonders if the two ever crossed paths…)

Sadomasochistic subtext in horror cinema is nothing new – you can trace a lineage through Edgar G Ulmer’s The Black Cat, Mario Bava’s The Whip and the Body and Hitchcock’s Frenzy, right up to the present day. It’s this connection which caused the perspicacious Parker Tyler, in his 1947 volume ‘The Magic and Myth of the Movies’, to write, discussing the critical prejudice against horror films: “It may be conventional to have contempt for those adults childish enough to shudder with pleasure at the sight of a lovely, seminude woman helpless in the arms of an irresponsible and repulsive synthetic man. But the obscure processes of sadism are certainly not contemporary news.” It was unusual, still, for a horror film to draw so heavily on the actual appurtenances of kink culture, as Hellraiser does: the subtext has become text.

To hear Barker tell it, the popular success of Hellraiser wasn’t so much a great leap forward but a continuation and confirmation of the work he’d been up to in the obscure trenches of short films and theatrical productions. “Doing a low-budget movie in a house in Cricklewood is the equivalent of the eight-quid play,” he told interviewer Peter Atkins. “I’d go further; low-budget moviemaking is fringe theatre, except that you can actually get the audience numbers I always wanted us to get. It’s what fringe theatre claims to be and so often isn’t – non-elitist, populist.”

And Hellraiser does put on quite a show for the punters – while thin on plot, what it offers, like Barker’s Lord of Illusions in its better moments, is the solemn majesty of ceremony, a sense of awe at the awful possibilities of the body in restoration and unjoining. Despite its moments of neophyte clunkiness, Barker’s film conveys a keen understanding of magic and myth, and its shudders of pleasure are undiminished.

Published 11 Oct 2017

Our guide to every film version of the great American author’s work, ranked from worst to best.

After 30 years David Cronenberg’s tour de force of disgust is as powerful and penetrating as ever.

The cult Italian horror maestro has influenced everyone from John Carpenter to Nicolas Winding Refn.