An aspiring filmmaker reveals how she set about channelling real-life struggles into her first script.

I disagree with Ben Wheatley’s logic that you shouldn’t criticise a film unless you’ve made one. The presumption seems to be that proven movie-makers are inherently superior. Which is the same as suggesting that because cat videos are popular among viewers, cats should run YouTube. Still, my exposure to movies and directors has fostered a yearning to, as Wheatley would have it, walk a mile in their shoes. This is not to make a bid for creative overlord status, but to expand my arsenal of expressionistic tools and release an impulse that has been festering for years.

“Mystification is the process of explaining away what might otherwise be evident,” wrote John Berger in his seminal visual culture book from 1972, ‘Ways of Seeing’. There is a lot of mystification when it comes to creative arts. Making movies seems an almost impossible goal if you dwell on the numerous steps and lucky breaks needed to transform an idea into a finished film. But highlighting difficulties is a form of mystification. Everything worth doing in professional life requires working and learning, a dance of progress and frustration. With labour and hardship as a given in any walk of life there is no reason to fixate on barriers within a particular industry, unless you actively want to deter hopefuls. Wherever a person has something to say, there is the potential for work of value. This isn’t to dismiss formal skills, but to stick up for a drive for personal expression which, when absent, makes technical achievements seem hollow.

Not everyone thinks this way. I expressed my filmmaking ambitions to a producer friend and his response was, “Why don’t you write a novel?” Novels are, obviously, a great form for channelling personal experience but they are not best-suited to what I want to express: loneliness and associated internal struggles. It’s true that great writers like Franz Kafka and Albert Camus had the whole ‘life is absurd and individuals suffer alone’ literary genre on lockdown. But the visual language of cinema makes it possible within a condensed time window, using few or no words, to show discord between a character and their environment. Through the body language of an actor coupled with the atmosphere of a scene, all manner of internal struggles can be suggested in a mysterious way that invites the viewer to interpret them. In Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, for example, momentary glimpses of Scarlett Johansson trying to pass as human are equivalent to pages of prose evoking the same.

“I was going through a really complicated time in my life – losing my best friend to cancer and not knowing how to deal with it,” says director Josh Mond, whose debut feature, James White, is about the pre-emptive grief that comes in waves when a loved one is dying. “I want to be a filmmaker and what better way to learn how to tell stories than exploring something you need to dance with in your head anyway.” The film is boldly personal. There is a son and there is a mother and there is no doubt that they are essentially Josh and Corrine, his mother, who died of cancer in 2010.

“Before making James White, I made a lot of conceptual short-form stuff and I felt very comfortable in a very visual world. There was more of a surreal-ness to it and I realised that that wasn’t appropriate. I was hiding behind that stuff – it became more like a defence mechanism.” The impulse to camouflage vulnerabilities is completely relatable, yet by not doing so, by stripping away the illusion of strength, you create the possibility of a very pure type of communication. James White does this through a volatile and messy tone, true to the wildness of watching your mum succumb to terminal cancer.

Another upcoming film, Mustang, offers a complete contrast. “There’s so many motives of fairy tale and even of mythology,” says French-Turkish director Deniz Gamze Ergüven, whose film is about the patriarchal oppression of five carefree sisters in rural Turkey. It is fuelled by real anecdotes, some of them lived by Erguven, some from her mother’s generation and some taken from interviews. The standard tone for such a story would be gritty realism, yet Mustang has a light-handed momentum propelling us forward even after tragic events. Every moment is a gorgeous treat for the senses and the coastal setting is magical.

“These are in no way naturalistic sets or places I’ve been growing up or spending my summers. They’re chosen to look bigger than life and surreal. I wanted to make shots that could be drawings,” Giving herself a fictional structure and stylised aesthetic goals helped Ergüven to make something new out of something old, while still retaining the gravitas of truth. Having goals beyond expressing a raw experience is essential if you actually want to reach other people – to communicate with them as opposed to release an unprocessed diary. It’s easy to spot a film that has total fidelity to biographical events and zero attention to engaging craft. The unfortunate paradox is that the more you breathlessly reveal of what happened to you, the less an audience is likely to care.

“What I do is I write all the things that cross my mind. Among them, I choose the moments that I can make relations between because obviously, I cannot say everything and, obviously, 16 years of my life cannot be a 400-page book. That means that I had a very minor, miserable life.” This is the perspective of Marjane Satrapi, a director whose calling card feature, Persepolis (based on her graphic novel published in 2000), is about coming-of-age during the Iranian revolution. “Of course, much more has happened but you choose – this is the importance of anecdote – a small story that makes you understand the bigger story. Take Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio De Sica, the story itself is very tiny but through this anecdote is the whole social situation of Italy after war. If you start talking about big ideas – big ideas are very abstract, it doesn’t mean anything. You have to talk about the things that you know and then they become universal.”

Persepolis debunked stereotypical bullshit about an Iranian identity and in the process revealed Satrapi as a highly blunt and brilliantly creative voice. We had a hearty talk entirely given over to the subject of turning personal experience into a film. “The biggest trip is not what you do around the world, the biggest trip is what you do inside yourself. The key of everything is the acceptance of who you are. If you accept who you are then you can make this person much better.” It’s encouraging that despite possessing one of the boldest personalities on the film scene, Marjane Satrapi is pretty sympathetic to the plight of figuring your shit out.

Psychological resolve is essential but without practical application all you will have to show for your life are good intentions and wasted time. Satrapi’s words are like a whip-crack: “You have to have a certain ethic in the work. You have to have certain principles and you have to stick to them. You cannot just be mellow and shallow in life. Time is the only thing that you can lose. You can lose your money and you can make more afterwards. You can lose your house – whatever. But the time that you have lost, you have lost.”

When she said this, it was like she peered into my soul, noticed how much time I waste every single day and delivered a speech designed to laser my weak spot into shrivelled non-existence. Another thing I have is idea debt, which is when you spend more time fantasising about your dream project than working on it. The more you dream about it, the more magnificent it becomes and the more discouraging your initial first draft will be when you finally set it down on paper.

“You have to have two people that you trust and you make them read. I always have that. When you tell the story, everything in your brain is completely obvious. You know the connections. Then people read it and they’re like, ‘I don’t quite get what that means’ and this is not because they are dumb. It’s because you didn’t write it in the right way. Rework it, rework it, rework it, rework it. It’s very important that what you’re saying should be understood the way you want it to be understood.”

Then there is the abstract kinship you can have with writers and filmmakers who have left their work as a legacy. For Satrapi, success is not about prizes or applause from high-flying contemporaries: “If you have arrived then you don’t move any more.” The way forward is to follow the path of light blazed by Crime and Punishment author and genius of Russian literature: “Fyodr Dosteyevsky is like the height of what you can do as a writer. Does it mean that I will ever become Dosteyevsky? No, but he’s like a light in the middle of the darkness. Am I ever going to reach it? No, but it’s not so much to reach the sun that is important, it’s the way that you go.”

I haven’t identified one true beacon but coincidentally clung to Russian literature during times of intense self-loathing and loneliness, finding solace in the bleak wisdom and gallows humour of the characters and their worlds. I also tend to agree with ’40s screwball director Preston Sturges that you should make audiences feel glad that they are watching your film. So something in between bleak and frothy – like Satrapi’s most recent film, the 2015 mental illness comedy-drama, The Voices.

Chatting with Satrapi, I start to feel like an imposter, carrying on like a person who is seriously about to write a feature script and seriously believes it might become a film. At least, lights in the dark have presented themselves in the course of researching this article. Like Josh Mond, I want to be bruisingly frank about the particulars of suffering alone. Like Deniz Gamze Ergüven, I want to create an artful framework inspired by real life but upheld by a sound fictional narrative. Like Satrapi, I want to crack on with the business of becoming better, assisted by trusted readers. It occurs to me to tell her about mental defects that may lead me astray but before I can really get into those, she interrupts with a motivational speech:

“You should say it. You should tell it. You should stop the hesitation. You want to tell a story, you just say it, then you find two of your best friends to read it and then you work on it again. Don’t be scared of doing it. First of all, when you are doing it, nobody is seeing it, so you are not in any kind of danger. Once you have the material in front of you, you can judge, but you cannot judge something before even having studied it because you are cutting your arms before even taking the weapon. Writing, just do it. In the worst case, it’s no good. In the best case, it’s great and you’re successful. There’s not so much risk that you will write it and then they will say, ‘Oh what you write is not good. We are going to put you in jail.’ The two bad things that can happen in life are you go to jail or you’re dead. The rest is okay.”

Published 14 Mar 2016

It’s possible for a movie to have a positive impact on society and the individual.

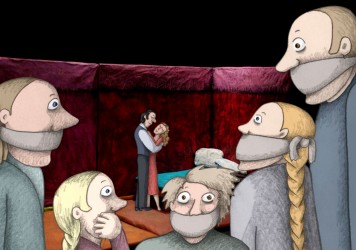

Signe Baumane describes her journey from a Soviet mental hospital to director of animated feature, Rocks in my Pockets.