The always excellent duo Joe Lawlor and Christine Malloy create a tense, gripping portrait of Rose Dugdale, who left behind a life of privilege to become a key figure in the IRA.

Rose Dugdale is a marginal but fascinating figure in the story of The Troubles. She planted her red flag in the annals of history by pulling off the biggest art heist of all time, organised with a view to syphoning the funds made from reselling a stash of paintings to help repatriate a group of incarcerated IRA members.

The filmmaking duo Joe Lawlor and Christine Molloy have an abiding interest in disguises, alter-egos and the idea of people transmuting into different versions of themselves. Baltimore offers rich terrain on which these concepts can thrive, not least in the idea that Dugdale was born a British blueblood who, through a series of revelations and the fast-tracking of a radical political consciousness, decoupled from a life of obscene wealth and ritual and became an outspoken warrior for class and gender-based injustices.

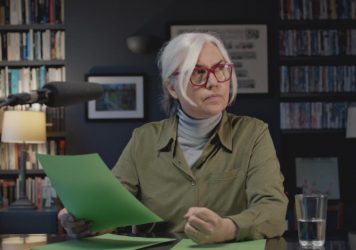

As essayed by the great Imogen Poots, Dugdale is presented as a person of almost cut-glass seriousness, where every taciturn aspect of her being is dedicated to serving the political cause at hand. The only respite we get from this coldly-obsessive nature is via a series of monologues she delivers to her unborn child, all of which are heartbreakingly coloured by the fact that she may very well be dead or in prison by the times this little person makes its way out into the world.

The film opens on the heist itself, with Dugdale and a group of male accomplices descending upon the grand Georgian stack of Russborough House in County Wicklow to terrorise its residents and nab a few pieces by some old masters. Rose’s MO is to use threat rather than violence, though the reception they receive by the entitled, dyed-in-the-wool aristos who live in the building ensures that a little bit of blood is spilled. Later, we move to the dinky getaway cottage where Rose et al hole up to make their negotiations, and it’s there where the recriminations and paranoia begin to fester.

The weight of Dugdale’s moral quandary is emphasised through a soundtrack consisting of eerie orchestral stabs – in fact, there’s no-one in the world who’s using the timpani in a more expressive and chilling fashion than Lawlor and Molloy. The story is captured, too, with a glassy precision which negates any element of sensationalism. The whole episode is presented as somewhat bleak and stifling, and it’s only until very late in the film that we see some physical suggestions that the net is closing in on Rose.

It’s a chilling and expertly constructed work which goes on to suggest that our finicky anxieties will end up getting the best for us. Poots brings fire to her role without just splaying it all on the screen, and she ensures that there’s a hair-trigger intensity to every one of her two-hander conversations throughout the film. It’s also a film about the messiness of life and the inherent unpredictability of people, where the idea of crisp, clean action devoid of emotional connection is simply impossible to achieve.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 21 Mar 2024

The film that was mooted in Lawlor and Molloy’s 2022 doc, The Future Tense.

A meaty, multifaceted role for the perennially underrated Imogen Poots.

The filmmakers have a thrilling grasp of their politically and philosophically rich material.

A young woman tracks down her biological mother in Joe Lawlor and Christine Molloy’s gripping study of trauma and identity.

Joe Lawlor and Christine Molloy reflect on matters of cultural identity in this hopscotching journey through time, space and the Irish Sea.

A spin-dried movie biopic that manages to be both playful and moving – another triumph for its brilliant directors.