William Castle wasn’t the first showman to use gimmicks in an attempt to lure cinema audiences. Smell-O-Vision, Hans Laube’s patented practice of pumping odour into theatres, arrived in 1960, making its solitary appearance in the Cinerama classic Scent of Mystery. Yet the idea had been kicking around as early as 1906, when Samuel Roxy Rothafel placed a wad of cotton wool soaked in rose oil in front of an electric fan during a newsreel thought to be about California’s Rose Parade.

Yet Castle remains the undisputed king of cinema gimmickry. This year sees the 60th anniversary of two of his greatest works, House on Haunted Hill and The Tingler, both starring the great Vincent Price. They were released in 1959, a year on from Castle’s Macabre, screenings of which saw ushers hand out Fright Insurance Policies – backed by Lloyds of London – promising to pay out $1,000 to audience members if they “died of fright” during the film. Time only emboldened the director’s love of gimmicks.

House on Haunted Hill concerns eccentric millionaire Frederick Loren, played by Price at his most droll, and takes place over an evening spent within a haunted house that Loren has rented to celebrate the birthday of his fourth wife, Annabelle (Carol Ohmart). He invites five guests, promising $10,000 to anyone brave enough to stay the night. It’s been said that the film partly inspired Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 horror, Psycho; Castle later said the same of Psycho and Homicidal, released one year later. (Castle’s film screened with a 45-second ‘Fright Break’, offering viewers who found it all too frightening the opportunity to leave early and get their money back… provided they signed a contract declaring them a ‘coward’ on the way out.)

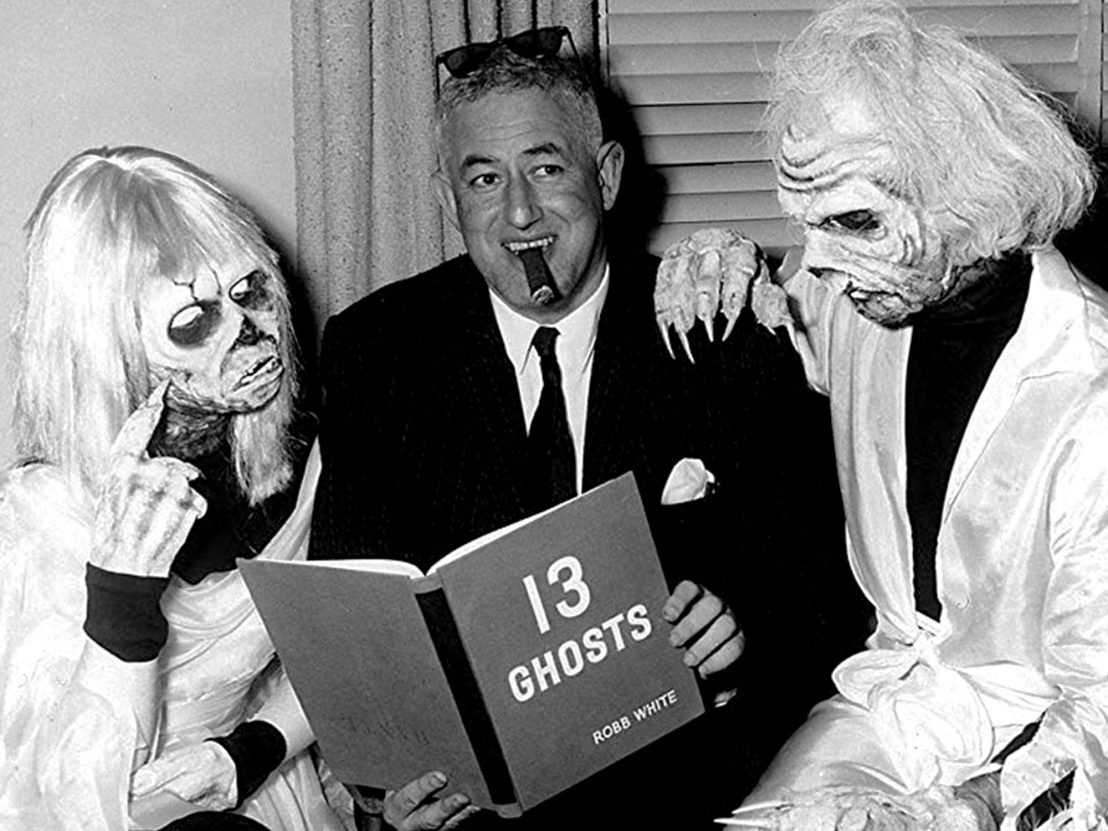

It’s surprising how much of House on Haunted Hill holds up today, but it’s the 4D gimmickry employed at the time of its original theatrical run that has preserved its legacy – Loew’s Jersey Theatre still occasionally hosts revival screenings using the old techniques. There’s a scene towards the end of the film where Loren tricks his wife into running into a vat of acid by scaring her with a plastic skeleton.

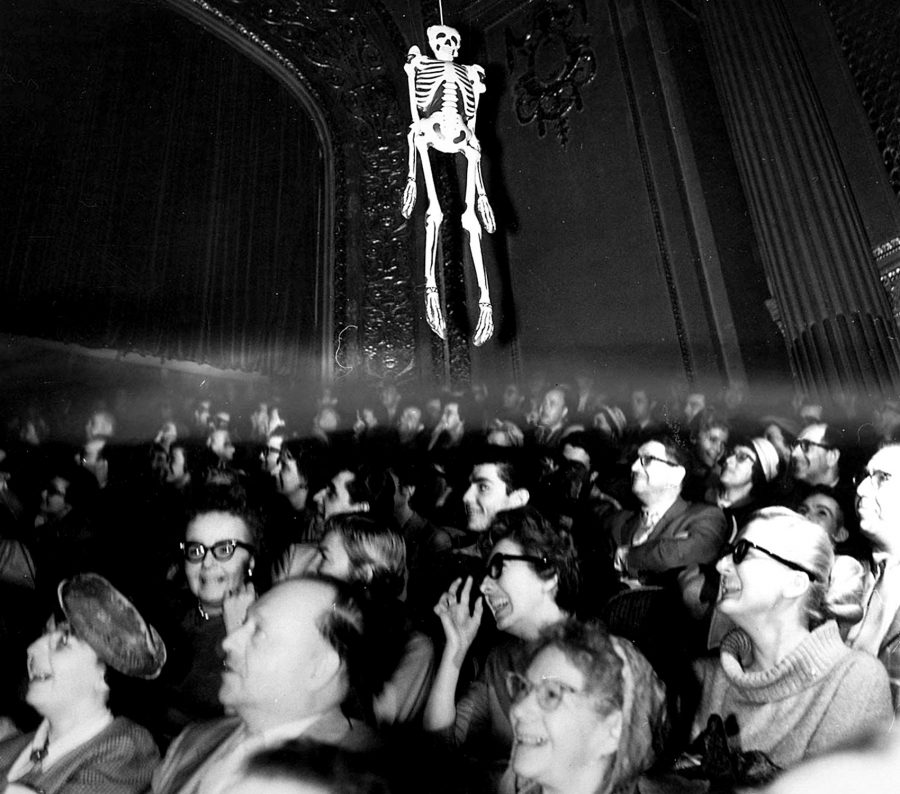

During screenings, Castle would deploy a gimmick he called ‘Emergol!’, releasing a glow-in-the-dark skeleton at the precise moment Loren deploys his on screen, with the physical skeleton then dragged above the audience’s heads on wires.

While House on Haunted Hill is the better film, The Tingler – in which Price plays a doctor who discovers a parasite that lives in human spines and feeds on fear – had the better gimmick. On entry to the theatre, the film’s posters warned that The Tingler would, at some point, break free during the film’s screening.

Castle even appeared on screen at the start warning viewers that they must scream to save their lives. During the film itself, Price broke the fourth wall to address the audience, declaring, “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not panic. But scream! Scream for your lives! The Tingler is loose in this theatre!”

The director called the accompanying gimmick ‘Percepto!’, which translated as some of the cinema seats being attached to surplus World War Two airplane wing de-icers, which vibrated and gave those sitting in the seat a short, sharp shock.

Castle was born William Schloss Jr in New York City in 1914, in time adopting the pseudonym (‘schloss’ being the German word for ‘castle’) for which he became so renowned. An orphan by 11, he was raised by his older sister Mildred. Then came the event, at 13, that changed his life, a performance of the play Dracula staring Bela Lugosi. “I knew then what I wanted to do with my life,” Castle wrote in his 1976 autobiography, “I wanted to scare the pants off audiences.”

The young Castle saw Dracula so many times he lost count, and eventually he met Lugosi himself. The Hungarian actor recommended him for an assistant stage manager position in the crew of the plays’ touring production. At 15, Castle got the gig, dropping out of school in order to take the role. He worked a variety of jobs on Broadway, mostly building staging, all of which proved useful in the years to come. Then came the first of Castle’s great stunts. Claiming he was a Broadway producer, he managed to obtain Orson Welles’ phone number, persuading him to lease him the Stony Creek Theatre – and that’s not even the most audacious part.

Before Castle had obtained the lease for the theatre, he hired the German actress Ellen Schwanneke – who had previously fled the Nazis – to star in a production of the play ‘Seventh Heaven’ on the Stony Creek Theatre stage. It should go without saying that he hadn’t obtained the rights to perform the play. The Actor’s Equity Association – the union representing American actors at the time – contacted Castle to inform him that he couldn’t hire Schwanneke because, “during peak season, American actors must be given preference unless the role is specifically tailored to suit a foreign star.”

Castle claimed he had written a play called ‘Das ist nicht für Kinder’ (he hadn’t), and hurriedly spent the subsequent weekend writing a play of that title and translating it into German. He credited it to Ludwig von Herschfeld (a fictional Austrian playwright). Then came the intervention of Hitler, via correspondence sent by Dr Joseph Goebbels, the Reichsminister of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, requesting Schwanneke’s attendance at a special reception in Munich. Castle quickly penned two telegrams: one to Hitler, one to Goebbels, and sent copies to every major newspaper.

They read…

“Cable to Adolf Hitler, Munich, Germany. Dear Mr Hitler: Ellen Schwanneke turns down your invitation. She has positively said no. She wants nothing to do with you or your politics. She will not return to Germany as long as you remain in power. Signed, William Castle, Producer/Director, Stony Creek Theatre, Connecticut. P.S. She’s working for me now.”

By the late 1960s, Castle had all but abandoned the gimmickry, focusing instead on films more serious in tone. By rights he should have been behind the camera for Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, remortgaging his home to secure the rights to the Ira Levin novel before it had even been published. But Paramount held firm on their desire for Roman Polanski to direct the film ,and Castle had to make do with producing, as well as a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo (we catch a glimpse of him outside the phone box Rosemary uses to contact the obstetrician).

Castle suffered kidney failure not long after the film’s release and within a decade he was dead, succumbing to a heart attack in Los Angeles on 31 May, 1977. He was 63. Throughout his remarkably varied career, Castle made moviegoing infinitely more interesting, more engaging, more exciting. In the words of John Waters, “William Castle is God”.

Published 31 Mar 2019

By Matt Turner

Whether cheap trick or clever gimmick, the use of stereoscopic techniques has constantly pushed the boundaries of the medium.

By Jen Grimble

The director’s classic “one shot” thriller introduced numerous new and innovative cinematic techniques.

By Elena Lazic

This immersive motion picture technology promises to put viewers ‘in the movie’ – but is it any good?