“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” Dorothy says this line excitedly – it’s thrilling to leave the drab sepia world of 1930s America for the glorious Technicolor of Oz. It’s soon turned upside down, a puff of red smoke and the Wicked Witch of the West appears, doing everything she can to stop Dorothy returning home. For all its wonder, Oz isn’t home. Its uncanniness frightens her, and through sheer will power she escapes. “There’s no place like home… There’s no place like home… There’s no place like home…”

When you’re undergoing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), one technique is to close your eyes and transport yourself to a safe space. For me, it’s my grandparents’ house. My therapist says the magic words I chose, and I’m sitting in my grandad’s armchair in their cosy living room, the scent of lavender wafting through. We do this when my treatment triggers something and I start to disassociate as my mind convinces me I’m reliving the past. A click of the ruby slippers, “There’s no place like home…” and I’m safe again.

I hadn’t made this connection between The Wizard of Oz and my PTSD until I saw David Lynch’s Wild at Heart. Despite being released in 1990, it was one of those rare moments when a hand reached out, took mine, and told me it knew how I felt. It wasn’t what I’d expected – wasn’t this just the pulpy one with Nicolas Cage in a snakeskin jacket? I hadn’t thought of Lynch as an empathetic filmmaker, as someone capable of tackling the psychological effects physical abuse has on women. In fact, if I’d known the film would be dealing with sexual assault, I’d have avoided it.

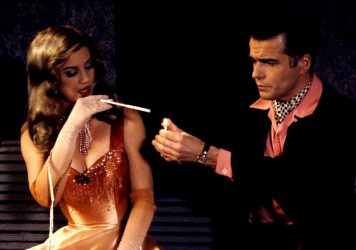

What distinguishes the sexual assault in Wild at Heart from Lynch’s other films is that Laura Dern’s Lula is given full agency in its depiction. Unlike the laughing gas-induced attacks in Blue Velvet or the mysterious murder of Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks, we don’t see the act itself so there’s no risk of it being confused for narrative pleasure; we see only the aftereffects on a female character we instantly fall in love with. She’s fun-loving, sexy, and in total command of herself. What’s more, her relationship with Sailor (Cage) is unmistakably romantic, and their sex life is shown to be fulfilling and consensual. Light a match, extreme close-up of a burning cigarette, and we settle in for a stream of post-coital duologues consisting of startling trust and honesty.

“Wild at Heart showed me that you can appear to be better on the surface while invisible scars lurk underneath.”

It’s clear that Lula has told Sailor about her trauma before, and it’s through their healthy sex life that she refuses to allow the rape to control her – she’s a survivor, not a victim. I didn’t feel that way. Like Lula and the statistical majority of other survivors, I was assaulted by someone I already knew. Lula claims she couldn’t talk about it with her mother, and neither could I – it wasn’t until I met my loving boyfriend that I learned to respect myself, to identify the spiral of depression I’d fallen into. And just like Lula, a significant part of that recovery came through not only tolerating but enjoying sex.

That’s not to say those demons have been laid to rest – far from it. But being able to write about it is a sign I’m on the road to recovery. Wild at Heart showed me that you can appear to be better on the surface while invisible scars lurk underneath. Just as I’m triggered by loud noises and sudden movements, Lula’s flashback erupts onto the screen when Sailor slams a window shut. Lynch uses the visual language of film editing to recreate a facsimile of post-traumatic experience. A cigarette calms her nerves, but it’s a short-term fix. Therapy isn’t an option for a woman on the road, not least in its financial cost, and her ‘home’ in the domestic sense is totally dysfunctional. She’s found a home in Sailor, and that’s beautiful.

While Lula clearly knows she needs Sailor, he’s less astute. He’s misguided, committed to an independent life of crime that sees him in and out of jail. In the end, he’s also Dorothy; after the Wizard leaves in his hot air balloon, it takes Glinda in her bubble-gum-pink orb to make him realise that his place is with Lula, that she is his home. Perhaps only Lynch could get away with a sequence like this in a film that’s otherwise coherent. It’s a necessary apotheosis – the Good Witch come to chase away the Wicked Witch of the West who frequently appears onscreen in the place of the violent acts committed against Lula. Together they douse her in water until she melts into nothing. “Oh, what a world! What a world!”

The scene I found hardest to watch in Wild at Heart sees Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe) taunt Lula. It realises the fear inherent to PTSD, that those traumas aren’t over, they’re ongoing and may come again. Against the peeling wallpaper of the bedroom our eyes are drawn to Lula’s blood-red heels as she draws on her cigarette, a moment of solitary bliss. Then Bobby asks to use her loo before pressing himself up against her, ordering her to say, “Fuck me!” It’s clear he wants to intimidate her, and he leaves soon after, as the camera closes on her shoes as she clicks her heels. She doesn’t say anything, but the direct parallel with Dorothy is heart-breaking. It’s hard to escape from the nightmare when you’re living it.

In Wild at Heart, Lynch gives this seemingly tame gesture from The Wizard of Oz, one of the most iconic images in cinema history, new significance. Lula doesn’t need to say anything for us to get the message – it’s her silence in this scene that’s so arresting, a realistic depiction of how the body can shut down when it’s being assaulted. She’s found her therapeutic methods, and we see her refusal to let it weigh her down. Her ruby slippers might not be magic, but Lula reminds us that it’s possible to leave our troubles behind, somewhere over the rainbow. I’d choose Kansas over Oz any day.

Published 17 Aug 2020

Exploring the suggestive imagery and symbolic language in the director’s 1986 cult favourite.

By Alex Denney

The original cast and crew discuss the making of this short-lived follow-up to Twin Peaks.

By Kaite Welsh

All hail the lusty, bitchy antiheroine of Clive Barker’s visceral 1987 body horror.