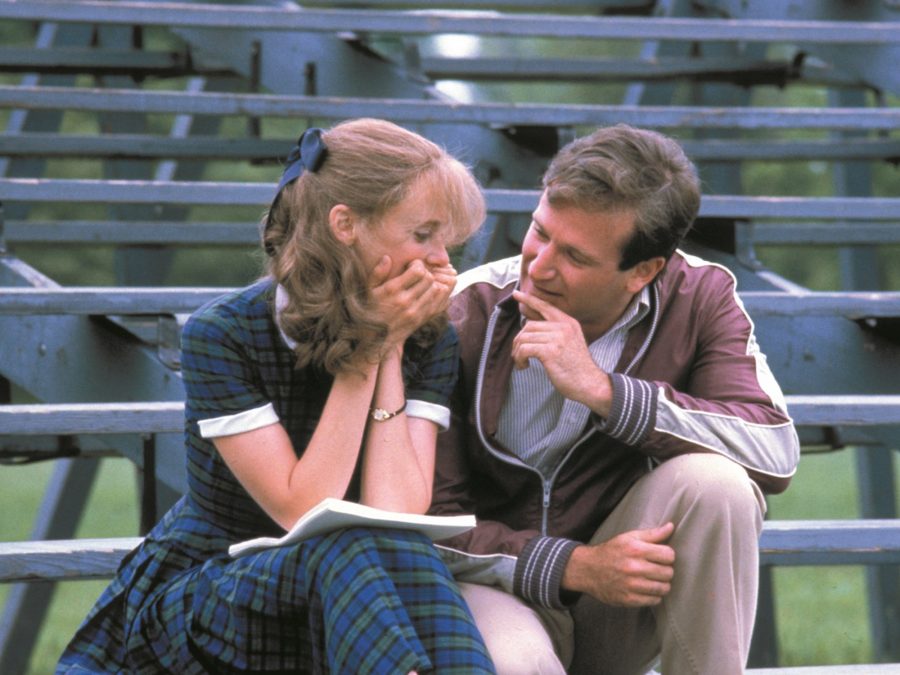

Robin Williams displays a remarkable emotional range with seemingly little effort as the lead character in George Roy Hill’s 1982 dramedy The World According to Garp. He doesn’t appear until the beginning of the second act, but he remains grounded at the centre of the film for the duration. While the unconventional story unfolds and colourful characters come and go at a quick and steady pace, Williams’ performance keeps the audience engaged and on track.

TS Garp (Terribly Sexy, Terribly Shy, or Terribly Sad depending on the moment) is a writer living in the shadow of his feminist icon mother. Garp was Williams’ second starring role in a motion picture – at the time, he was best known for the television show Mork and Mindy, a surprise hit that derived its energy from Williams’ unique brand of hyper-energetic improvisational comedy.

In Garp, Hill reined in Williams, keeping him closely tied to the script and his improvisations to a minimum. Williams was the straight man, letting the odd inciting incidents of the film and the sharp, deadpan dialogue of other actors draw the laughs. In so doing, Williams tapped into a deeper level of his talent, drawing the viewer into the love and heartache, comedy and tragedy of Garp’s life.

Garp’s mother, devoted nurse Jenny Fields (Glenn Close), looms large over him. Garp grows up without a father because his mother didn’t want a husband, only a man’s sperm so she could have a child. During the war, she took advantage of a dying flier’s incurable priapism to get herself pregnant. She raises Garp herself, perfectly comfortable in her decision to be a single mother. She is honest with her son about his conception and displays little tolerance or sympathy for his natural curiosity about his father.

Williams evokes all the shades of resentment and frustration that come from growing up in Jenny’s shadow. When her hastily written memoir becomes a sensation and catapults her to the forefront of the feminist movement he wallows in resentment. He puts up a brave front, complete with a skin-deep smile and hunched shoulders, when he is recognised in public not for his own novel, but for being the “bastard son of Jenny Fields.” The frustration is understated, but anyone who has ever felt unappreciated in life can see it quite clearly.

Garp’s dejection becomes anger because no one is buying his book, yet Jenny’s best selling tome has been translated into Apache. He dejectedly tells his wife Helen (Mary Beth Hurt) “Not even Shakespeare or Dickens has been translated into Apache.” She soothes his mood when she reveals she is pregnant. Pregnancy revelations in film can easily drift into cliché with their obligatory tears, joy, and surprise.

This one isn’t all that different. However, Williams plausibly makes a wide arc in this scene from unquenchable jealousy to paternal expectation and pride. It makes Garp’s transition into the happy house husband and family man believable.

Helen, aside from being Garp’s artistic champion, is a college literature professor and the family breadwinner who makes his life possible. Garp loves the arrangement – he enjoys taking care of the house and preparing family meals complete with food-stained aprons and mashed potatoes. His joy is barely contained as he excitedly shares adventures and plans with the boys. It’s a stark contrast to Helen, who listens quietly while tamping down her lust for her handsome but empty-headed student Michael Milton (Mark Soper).

The joyous family man persona evaporates when Garp learns of Helen’s affair – his anger is palpable and unpredictable. He leaves home with the boys, impatiently shoving them through dinner and a movie. This is a Garp we have not seen, certainly not the man who experienced profound joy in simply watching his kids sleep. Despite the tragedy that ensues, husband and wife eventually reconcile, bringing their story arc full circle.

Garp likewise brings things full circle with Jenny. As he matures and settles into his family life, Garp sheds his jealousy of his mother’s success. Instead, he is jealous for more of her time and wants to be her protector. Jenny’s life is absorbed in helping the community of broken souls that have amassed around her at the family compound, and Garp is openly concerned that all these new people are taking advantage of his mother.

At heart, though, we get the sense in his meditative moments that Garp yearns for the nostalgia of the quiet home of his youth and for his mother’s undivided attention that he once felt smothered by. In their last scene together, he tells her, “I never needed a father.”

Throughout the film, Williams ably communicates Garp’s emotional presence in physical ways beyond dialogue. When Garp’s transgender friend Roberta (John Lithgow) casually kisses him goodbye on the lips, Garp’s face registers shock, confusion, and acceptance all in rapid succession. The brief moment happens in the background of a shot that is focused on Helen and Jenny and is easily missed on first viewing.

Another more direct moment near the film’s end finds Garp in sad reflection, perhaps sensing that tragedy is approaching. When the phone rings with the news of his mother’s death, Garp’s agony rises to the surface. A lifetime of sorrow over misplaced resentments and missed opportunities for a stronger connection become evident in the pain on his face without a word being spoken.

Published 28 Jul 2022

By James Clarke

The late actor is at his dangerous, dynamic best in this melancholy fantasy from Terry Gilliam.

The French screen idol is at his most open and vulnerable in Luchino Visconti’s 1960 crime drama.

Her easy charm and chemistry with Clark Gable elevates this otherwise unremarkable workplace rom-com.