In 1993 Tracey Moffatt’s innovative supernatural horror beDevil became the first feature film directed by an Australian Aboriginal woman. Like the artist and filmmaker’s prior short, Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy, it was selected for the Cannes Film Festival, appearing in that year’s Un Certain Regard section.

Despite Moffatt’s international renown as an artist and the fact that it remains her sole feature, beDevil has subsequently been rather surprisingly overlooked. Fortunately, it screens as part of the Barbican’s forthcoming season, Homeland: Films by Australian First Nations directors alongside work by Leah Purcell, Warwick Thornton, Rachel Perkins and others.

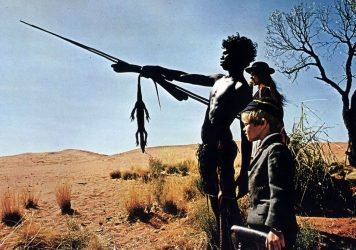

Indebted to Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan, beDevil is an anthology horror consisting of three unconnected ghost stories which Moffatt heard as a child from her family. The first, ‘Mr Chuck,’ concerns a young boy who encounters the spirit of an American GI that drowned in a swamp on Bribie Island during World War Two and continues to haunt the locale.

The second, ‘Choo choo choo choo,’ centres on a family living in a house beside a railway track somewhere in the Outback who are beset by the clamour of invisible locomotives and the spirit of a young girl killed on the tracks. Finally, ‘Lovin’ The Spin I’m In’ tells the tragic tale of a couple from the Torres Strait Islands who mysteriously died far too young and are forever compelled to reside in a condemned warehouse.

While it might be understandable that beDevil is regularly characterised as ‘Indigenous Gothic,’ Moffatt herself bristled at those who were only able to engage with her work through the lens of her identity. Across her various modes of art practice, she has addressed Indigenous stories and people, but the stories in beDevil recount hauntings by ghosts of various ethnicities and nationalities and they are plaguing people of similarly diverse backgrounds.

The interplay of cultures is undeniably both prominent and pertinent, but the frame of reference is broad and intersectional. Perhaps as striking as the foregrounding of Indigenous characters is the agency given to women – who act as the primary framing voices for all three stories – as well as characters from immigrant backgrounds or who otherwise don’t conform to societal expectations.

However, the radicalism of the film doesn’t end with issues of representation, and it could be argued that its aesthetic and formal creativity is why beDevil still feels quite so invigorating to a contemporary audience. Visually, the film resembles some of Moffatt’s most famous photographic work, in its use of impressionistic studio sets painted in bright saturated colours – particularly her 1989 series, Something More.

The sets are one area for which Moffatt cited Kwaidan’s influence as well as Australian landscape artists like Russell Drysdale. The design and lighting of the sets, intentionally highlighting their artificiality, is both incredibly evocative and uncannily atmospheric. It also emphasises the layers of story and memory that instruct the film’s form and its thinking about haunting.

Even within the three separate sections of beDevil, there are multiple levels of representation. Two of the three chapters include faux-documentary framing devices alongside the hyper-real presentation of the actual events, while in the third section people recount elements of the narrative within the narrative itself. The layering of story and temporal shifts unmoor us and collapse time, allowing Moffatt to explore the prolonged impact of memories and the way that fables become enmeshed in communities through the years. It feeds into the sense that as much as tales of phantoms, beDevil is about the haunting of a place by its past.

In this sense of landscapes holding on to painful memories, it clearly engages with the specific histories of Australia’s Indigenous populations, but it also speaks more broadly about the nature and impact of remembrance and storytelling. beDevil’s most unnerving aspect might be the potential it posits for the horrors of the past to come crashing, terrifyingly into the present.

beDevil screens as part of Barbican’s Homeland: Films by Australian First Nations directors season, which runs 2-23 February.

Published 2 Feb 2022

By Elena Lazic

Jennifer Kent follows up The Babadook with a gruelling yet vital portrait of colonialism in 19th century Tasmania.

By Aimee Knight

Warwick Thornton’s gorgeous period drama cuts to the heart of Australia’s dark colonial past.

To celebrate the release of Sweet Country, seek out these amazing works directed by and starring native Australians.