“Let it be said, they found us very close together, in the light.” After the success of 1968’s The Lion in Winter, the next project by director Anthony Harvey and writer James Goldman was expected to reach similar heights. Instead, They Might Be Giants, a romantic comedy about a widowed judge who thinks he’s Sherlock Holmes (spare a thought for the marketing team), was released in 1971 to lukewarm reviews.

Goldman’s original play, directed by Joan Littlewood and starring Steptoe and Son’s Harry H Corbett, hadn’t quite worked on stage in its brief London run. Harvey was reportedly unhappy with the finished cut of the film, too; with its vanishing characters and lapses in narrative logic, it’s clear that the many cuts made were almost fatal.

And yet They Might Be Giants has gained a cult following in the 50 years since its release. Its emotional power and zany charm linger in the mind much longer than its obvious failings. Devotees of Arthur Conan Doyle’s world-famous sleuth will certainly appreciate George C Scott’s lead performance. Deductions are made, leads are pursued, and a violin is horribly murdered. The real twist, though? They Might Be Giants isn’t really about Sherlock Holmes at all. The clue is in the titular reference to a certain Man of La Mancha, whose offbeat worldview is approvingly cited by our “Holmes”.

Much of the film’s running time is spent following Justin Playfair, a tragic character lost to psychosis after his wife’s death, tilting at windmills in a grimy New York City as Joanne Woodward’s Dr Mildred Watson scuttles after him. She’s a Dr Watson rather than the Dr Watson, but that’s more than enough for this counterfeit Holmes.

Justin’s brother Blevins (Lester Rawlins) wants him committed so he can use his estate to pay off some very sinister debtors. Watson, an eminent psychiatrist working in a hospital she loathes, jumps at the chance to observe a rare case when she’s brought in to sign off on the diagnosis. Once she realises that Justin is in genuine danger, the game is well and truly afoot.

In Mildred’s dingy flat hangs a painting of Don Quixote riding his white horse, Rocinante. An old man on a beast as weary as he is, or a noble warrior atop his trusty steed? The answer, of course, is both.

Justin’s obsession with an all-powerful, monstrously cruel “Moriarty” conceals a mind keenly aware that Blevins is plotting against him. His Holmes identity is a shield for a supremely rational man blindsided by grief: anthropomorphising it makes it solvable, explicable. There’s a quietly heartbreaking moment when he comments, still in the third person, on Justin’s late wife’s “pretty name”. For his Holmes persona she’s just another stranger: a name in a case file, somebody else’s loss.

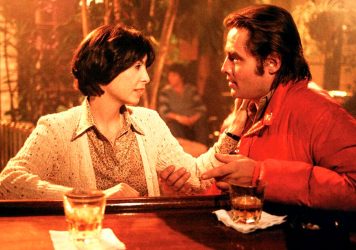

Early in the film, he brutally deduces that no one that Mildred loved ever loved her back, and the truth of it is all over the doctor’s face. Her stunned silence when Justin finally, tentatively asks her to dinner says everything: the disbelief that something which only happens to other people is finally within her grasp. Woodward and Scott are both astonishingly good, a pair of perfectly matched misfits, treating the brutal homogeneity of polite society with the cheery contempt it deserves.

John Barry’s theme, rich in suppressed feeling, hints at the film’s ultimate truth. It lies in kindly librarian Wilbur Peabody’s (Jack Gilford) cherished fantasies of being the Scarlet Pimpernel. You can see it in the Baggs, a sweet old couple (real-life husband and wife Worthington Miner and Frances Fuller), the owners of a student-free school for arborists who have spent years alone together with only their carefully pruned topiary for company. And it’s behind switchboard operator Peggy’s (Theresa Merritt) yearning to help a frantic young woman, the bureaucrat’s mask slipping as she turns to Holmes in tears. “You care!”, he breathes, mid-reproof.

They Might Be Giants reminds us that we all want a little romance and adventure in our lives, to feel as though someone understands our needs. In the end, there’s a beginning: the duo face Moriarty side by side in Central Park in the film’s ambiguous final scene. Is the bright light they see from the headlights of the hitman’s car, or has Mildred joined Justin in his delusion forever?

Someone will die tonight, but will it be them or Holmes and his Boswell, facing their nemesis one last time so that Justin Playfair and Mildred can live again? Time for our heroes to make a stand – like the lawmen in Justin’s favourite westerns – and step into that searching light. The final mystery is solved. Holmes and Watson, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Justin and Mildred: inseparable in life or death. We stand on the threshold with them, the choice ours to make.

Published 6 Jul 2021

Joan Tewkesbury’s sole directorial effort stars Talia Shire as a woman on a journey to rediscover herself.

A copyright dispute around 1984’s ‘Sherlock Hound’ freed the Japanese animator to establish Studio Ghibli.

By Thomas Hobbs

Billy Wilder’s 1951 noir has obvious parallels with our current age of fake news and alternative facts.