Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger created some of the most celebrated and lavish British films ever made. Their colourful, magical vision mixed innovative visual stylistics with heartrending, poignant human drama that seem at once deeply British and yet otherworldly. Even when dealing with a topic such as war, they never forgot that cinema was a quasi-fantastical entity, one that could travel beyond the limits imposed on other narrative media and tell intimate stories of whole lives in mere hours.

In terms of scale, this is never bettered in their career than in their 1944 film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp; a film about ties to home, friendship and growing old. Powell and Pressburger’s film tells of the intertwining lives of Clive (Roger Livesey) and Theo (Anton Walbrook). They first meet during a diplomatic spat in Berlin during the years of the Boer War. Surviving a duel, the pair become the best of friends. They both fall in love with Edith (Deborah Kerr) though she eventually marries Theo. In the years towards the end of World War One, Clive and Theo are reunited but are scarred by the fighting, with Theo now a prisoner. Clive falls for a nurse called Barbara (Kerr) due to her likeness to Edith and marries her.

Many decades later, Theo is again in Britain, this time having fled the Nazis. He meets Clive once again who helps secure him citizenship. But has Clive really learned the lessons from previous encounters enough to face a new, more brutal enemy or is Theo the bearer of some stark truths regarding his friend’s future?

Like many of Powell & Pressburger’s films, Blimp is a Technicolor masterpiece, shifting across eras and locations with startling ease. It’s surprising to find each set and location feeling so real. The film’s deliberate temporal shifts are marked by differing visual style and flourishes, with only the three characters played by the ageless Deborah Kerr remaining a constant (the third being Clive’s World War Two driver, Angelica “Johnny” Cannon). With such shifts comes a natural inclination towards studio filming but this doesn’t limit the use of real locations during the film. In fact, many of the real locations benefit from the emphasis on dreamlike visions of buildings and places, bringing reality to the more fantastical, romantic elements.

In spite of travelling temporally and physically throughout the film, London features surprisingly often. In fact, a raid on a Turkish bath by an over keen soldier, one who breaks the rules during an exercise to test the newly formed Home Guard, opens the film and in many ways bookends the main argument of the narrative: that Clive has been left naïve by his gentlemanly life and is too honour bound to be a truly effective counter to the growing threat of Nazi Germany. London appears melancholy due to this, a place where a very particular way of life is crumbling in the face of the new war, losing a piece of itself with every conflict.

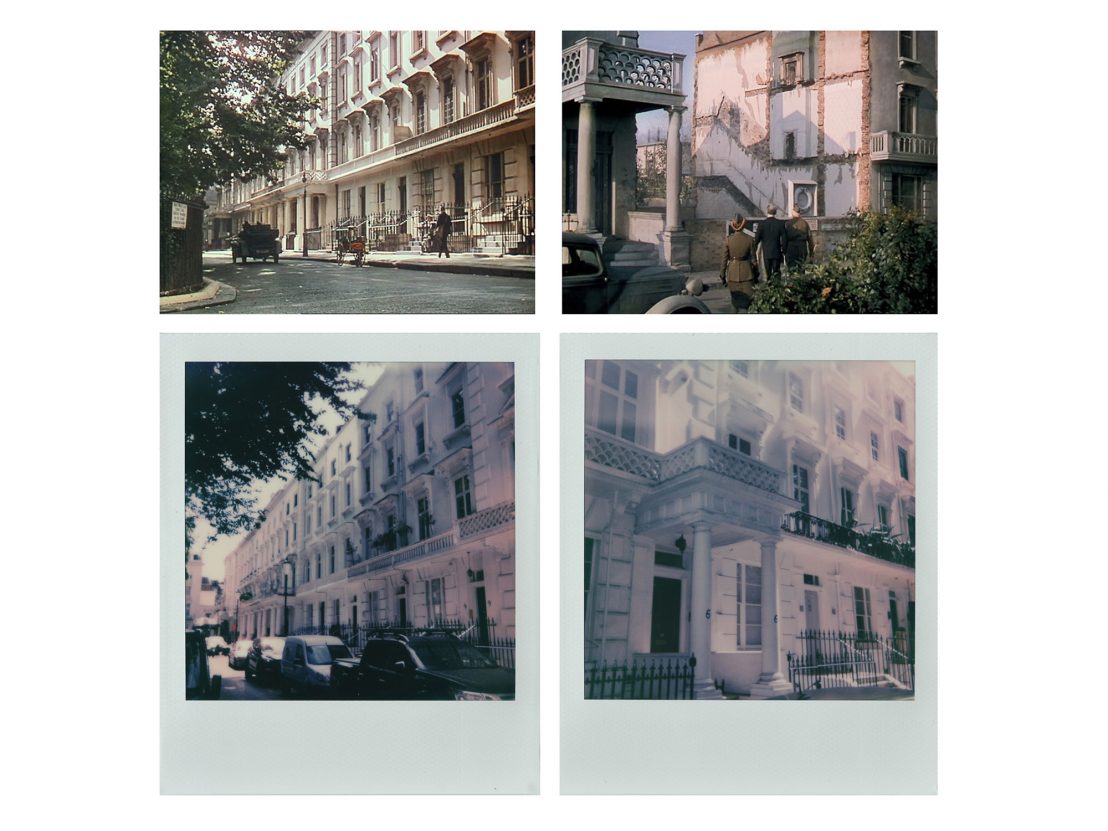

A sense of home is particularly important to the film and the question of what essentially constitutes one. The main home we see is the house that Clive moves into after World War One with Barbara. The house stands at 15 Ovington Square in Chelsea and, besides the dramatic increase in the number of cars, is today exactly as it was.

The home here is seen as important as it’s clearly more than bricks and mortar: it is an embodiment of memory, of those loved and lost, and of defiance in the face of ongoing tyranny. It is the people within it, and particularly the presence of Barbara, that makes it so vital. In a powerful speech later on, Theo makes this point; that without the presence of loved ones, what really is a home? It’s telling that Powell in particular chose to ground this with a real location rather than a fictional façade. This building is the reality of the film, filled with happy memories, friends and loved ones.

This is essential to what happens in the following decades and later in the film too. We begin to see the difference that this war brings when Theo is again reunited with Clive and is waiting with Johnny to listen in to Clive’s eventually cancelled broadcast. Clive is heartbroken at having been cast off by the BBC but is spurred on by his friends in becoming a pivotal leader of the Home Guard. When the chaos of the surprise attack is over, the film concludes again on this house, though something has changed dramatically.

The home has been blown up during an air-raid and is watched over by Clive as leaves drift on the Emergency Water Supply that now resides in its place. He is joined by Theo and Johnny as a parade passes with the soldiers who tricked him during the exercise. His feelings are mixed but eventually optimism wins through.

It is a film about the acceptance of time passing and what that does to a person’s pride. Clive’s acceptance is hopeful but also tinted with melancholy. The demolished house was actually shot over the road in Ovington Square and the difference in the houses that were built in its place, alongside the ornamentations that mark the original houses in the shot, can be seen from number six onwards.

At the end, Clive has lost the physical embodiment of his home and his sense of usefulness. Yet, when accompanied by his friends and his memories, Powell and Pressburger use the absence of Clive’s house to show that a home is something more than a roof over the head but equally something carried within us and those we share our lives with.

With thanks to Polaroid Originals.

Published 27 Jun 2020

By Adam Scovell

Maryon Park in Charlton lies at the beguiling centre of the Italian director’s psychological mystery.

By Adam Scovell

Visiting the scene of the director’s penultimate thriller, set in a bygone Covent Garden.

By Adam Scovell

This historic fortress is the scene of some unsavoury goings on in Robert Hamer’s classic Ealing comedy.