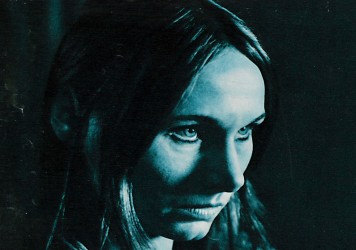

The first five minutes of Sidney J Furie’s The Entity introduce its protagonist, thirtysomething Carla Moran (the extraordinary Barbara Hershey), in a dynamic, fast-cut sequence. A rapid succession of scenes shows her working in an office, then studying in a night class, then returning to her LA home, where she locks the front door behind her, checks on her two young sleeping daughters Julie and Kim, greets her teenaged son Billy (David Labiosa), and retires to her bedroom upstairs.

All these scenes are marked by their brisk pace, and by their vision of a woman constantly in motion. Though Carla may struggle to pay the rent, this single mother is on the go and working to do the best for herself and her family. She is the embodiment of female independence and progress.

By the film’s sixth minute, all that forward momentum is brought to a juddering halt as Carla is attacked and raped in her own bed, with a jarring, brutal physicality that feels like an assault on the viewer too. By the time the three children have rushed into the room, Carla’s assailant is nowhere to be seen. “You just had a bad dream, that’s all,” a confused Billy reassures his mother – but the assault repeats itself, becoming a serial pattern of intimate, non-consensual incursions against Carla’s person, leaving scars, bruises and bite marks as evidence of a tormenter who otherwise remains invisible.

The ambiguous nature of these attacks – all at once viciously corporeal and otherworldly in nature – is brought into sharp focus by the different groups who end up trying to help Carla. Dr Phil Sneiderman (Ron Silver), a staff psychiatrist at the university clinic who takes a not altogether welcome shine to Carla, is insistent that the attacker is merely a psychological projection of Carla’s own past trauma, while a team of parapsychologists, led by Dr Elizabeth Cooley (Jacqueline Brookes), quickly sets about trying to measure, record and even capture her invisible assailant. The film itself gets to have it both ways, generating horrific genre thrills from the scenes of assault, while furnishing plenty of social and psychological subtext to all its supernatural violations.

Carla comes from a history of violence, and is surrounded by invisible men. Abused by her father (who was a priest) as a child, she fled home, and married at age 16 – although a fatal accident took her husband away from her while she was still pregnant with Billy. Her second partner – “old enough to be her father” – vanished after the birth of Julie and Kim. Her current boyfriend Jerry Anderson (Alex Rocco), also notably a lot older than her, is conspicuous entirely by his absence for the first half of the film, and treats her both as a child and a sex object, insisting that she put on the lingerie that he had bought for her for his ‘homecoming’ (an expression resonant with sexual unease).

Meanwhile the husband of Carla’s best friend Cindy (Margaret Blye) is also only heard rather than seen for the first half of the film, and is another menacing male figure with an insidious stranglehold over a woman (“I ought to leave him,” says Cindy, “you know, if I had the courage I would.”).

The home that Carla shares with her children is full of looking glasses, making it a veritable hall of mirrors whose surfaces reflect and refract the many physical outrages that Carla endures. One rape scene comes just after she has examined her face in the bathroom’s triptych of mirrors, and involves her face being forcefully pushed into a mirror. After another nocturnal intrusion, she smashes all the mirrors in her bedroom.

In this reflective environment, it becomes easy to follow Dr Sneiderman in regarding Carla’s assailant as a mirror to her psyche: an imaginary manifestation of the sexual trauma which she suffered in childhood at the hands of her abusive father, and from which, even in adulthood, she can never escape.

Yet on another, wider reading, Carla’s opponent is the ever-present, repressive power of patriarchy itself, which, whether in the form of Jerry, of Sneiderman and his pipe-smoking, patronising colleagues, or of a determined, demonic hypermasculine malefactor, cannot brook the notion of a woman running her own household free of male influence, interference and control.

“I won’t fight you,” Carla tells Sneiderman, submitting herself, at least at first, to his scientific scepticism despite knowing to be true what he dismisses and denies: that there is something deeply irrational afoot. Later she echoes these words again, saying, “I’m going to cooperate with him,” only this time, in a disturbing parallel, she is referring not to Sneiderman but to the transgressive poltergeist whose manhandling of her while she was asleep led to a shame-riddled orgasm.

All that remains for Carla is agonising surrender. Reflecting all the men who want a piece of her or casually fail to respect her autonomy, Carla’s attacker – invisible yet tangible, disembodied yet deeply destructive – is a figure for the ingrained misogyny which so many women must learn to accommodate in their lives. His only words – indeed, the final, shocking words of the film – give full expression to his domesticated brand of casual, woman-hating privilege: “Welcome home, cunt.”

Frank De Felitta adapted the screenplay for The Entity from his own 1978 novel of the same name, and both were loosely drawn from the real-life case of Doris Bither – but Furie broadens the themes to create a diabolical variation on the “woman’s picture”. Charles Bernstein’s melodramatic orchestral score brings a touch of Hitchcock, while the rape scenes come, for all their wrenching aggression, with a surreally abstract quality owing to the perpetrator’s absence.

Here Carla learns both to fuck the patriarchy, and to live with it, in the hope that her children’s generation might have it better. Invading a similar domestic space to William Friedkin’s The Exorcist and even Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist, The Entity is a bittersweet modern ghost story that dramatises the awful compromises and sacrifices that women make every day just to get by in a man’s world. Essential viewing.

The Entity is released by Eureka Entertainment on Blu-ray on 15 May, 2017.

Published 15 May 2017

By Anton Bitel

Adam Schindler’s directorial debut Intruders offers a suspenseful blend of tragedy and trauma.

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?

By Anton Bitel

José Ramón Larraz’s chilling 1974 film Symptoms is coming to Blu-ray and DVD this month.