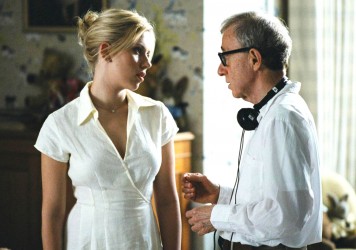

Woody Allen’s first attempt to strike ‘comedian’ from his multi-hyphenate status began with 1978’s Interiors, described the following year as a “violent act of self-mutilation” by film writer James Monaco in the first edition of ‘American Film Now: the People, the Power, the money, the Movies’. Allen quickly acknowledged the widespread sense his “earlier, funnier” movies were preferable by putting that sentiment in the mouth of visiting extraterrestrials in 1980’s Stardust Memories, but the blowback never eradicated his continually recurring desire to be a dramatist.

After his initial run of comedies (as close to universally acclaimed as possible) and setting aside revisionist contrarianism, it wouldn’t be hard to separate his films from the widely praised and those instantly, irrevocably dismissed. Some directors have their follies age into masterpieces, but there’s no Heaven’s Gate in Allen’s filmography; consensus at the moment of release tends to stay locked forever after.

Look at some reactions to his two films from 1987 to consider at how people used to extol his more marginalised work. The lightly charming Radio Days, a nostalgic recap of growing up with the title medium, was released first. Andrew Sarris took this time to tackle head-on (in an essay called ‘Is Woody Strictly Kosher?’) the anxiety of influence plaguing Allen and irritating his detractors. The problem wasn’t merely that Allen openly copied entire Bergman sequences or spoke forthrightly about his admiration of Chekhov, but that he never seemed to improve on or add to them. Noting that, “in cinema Allen is clearly not Chaplin nor Keaton nor Bergman nor Fellini,” Sarris argued the ’80s Woody was “more relaxed than he used to be,” leading to fleeter work, “a liberation of his unconscious” and greater tonal control.

1987’s other Allen film was the strenuously dramatic September, and the question of influence versus the merely derivative arose again: “Chekhovian” was how Richard Schickel described the “humourlessness,” echoed pejoratively by Vincent Canby at The New York Times (“neo-Chekhovian”) and all the way down to Premiere magazine journalist Marcelle Clements, who predicted this fixation on a single adjective before the movie was released – “You can bet your boots that the word ‘Chekhovian’ will be uttered at least once by everyone at the table”.

“It’s hard to convince an unsympathetic viewer that Allen’s eternal reference points go beyond the wishfully invoked.”

Allen’s stated influences are obvious and constrictingly limited to a handful of great books and films that haven’t obviously expanded since the time he started making movies. It’s hard to convince an unsympathetic viewer that his eternal reference points go beyond the wishfully invoked. One can insist Allen’s body of work only “works” as a whole – i.e., that a classical autuerist approach needs to be taken to appreciate and mine the resonances of his work.

In an otherwise non-notable 1983 review from Orange Coast, a lifestyle magazine for Southern California, in which one Kerry B Brougher compares Allen’s films to the paintings of Barnett Newman in order to argue that the individual movies are meaningless when evaluated piece by piece: “one work alone ceases to be a self-contained unit, relying instead on the relationship and juxtaposition of other works to bring it to light.” Defending Allen in 2011 for Sight & Sound magazine, Brad Stevens took a nearly identical tack: “his films cannot be understood individually – and impression reinforced by their repeated motifs (magic tricks, independent young women, embodiments of death, groups of nostalgic men), actors, narratives.”

One viewer’s stale repetition is another’s fascinating series of variations on a complicated theme, whether the director is Allen or South Korea’s similarly inclined Hong Sang-soo. There’s nonetheless something unconvincing to this Allen agnostic’s ears about insistent claims that his worst films amplify one other rather than provide diminishing returns, an argument more often blankly proffered rather than convincingly argued for in detail.

Skeptic though I am, I have a soft spot for 2003’s much-reviled Anything Else, which now seems like a model test case for revisionist apologetics. Allen’s next-to-last movie shot in Manhattan was his last made under the auspices of DreamWorks (hence his last ‘studio film’). When not onscreen in his ’90s comedies, Allen normally cast a lead actor who’d attempt to mimic his mannerisms to distracting effect (Kenneth Branagh in Celebrity, John Cusack in Bullets Over Broadway). In Anything Else, he doubles down, sharing scenes with Jason Biggs, whose nervous stammerings and ineffectual complaints multiply those of his creator.

The plot barely exists: Biggs plays Jerry Falk, an up-and-coming comedy writer trapped in an obviously awful relationship with Amanda Chase (Christina Ricci), an incredibly selfish and demanding “aspiring actress” who makes Jerry’s life a misery after an initial period of sexual bliss. When not with Amanda, Jerry kills time with David Dobel (Allen), a public school teacher masquerading as a comedy writer, who shares his hard-earned wisdom. These soundbites are indistinguishable from numerous Allen lines over the years, though there’s even less context for their pessimism (“What you don’t know won’t hurt you, it’ll kill you”).

Dobel and Falk – his young double – have a lot in common (“Fear of death? That’s funny, I have that too”). The apposite reference point is (to cite critic Bilge Ebiri) Dostoyevsky’s The Double, with Allen’s violently unbalanced older mentor egging on his younger, more passive friend. There are pointed allusions to Annie Hall (a scene in which it’s Biggs rather than Allen who’s appalled at a sudden social encounter with cocaine), climaxing with Falk leaving the city for Los Angeles at Dobel’s urging. It’s as if the younger man is being urged to leave before he stagnates into self-parodic Upper East Side ossification, and a geographical preview of where Allen’s work would be going.

Anything Else isn’t a great lost masterpiece, but it’s an enjoyably angry, non-rancid look into Allen’s psyche and the accidental dividends of his working methods. Without making the claim of routine mastery of spatial complexity, there’s a triple split screen scene in which Biggs’ living room takes the left and right rectangles, with Danny DeVito’s end of a telephone conversation in the middle. His dropped-in presence creates a visual obstacle allowing people to cross from left to right square unseen, sparking sudden surprises when they emerge.

Such accidental moments of visual discovery and revealing hatred seem like the strongest grounds for defence. Recently, The New Yorker’s Richard Brody was admirably forthright in recommending Cassandra’s Dream as a film with one singular purpose: “to depict human life as cruel, grim and doomed,” a POV most valuable for being “offered so forthrightly.” Like Philip Roth’s disclaimers about his writer alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, Allen’s constant claims that his onscreen persona is a totally fictional construct are unconvincing: whether drama or comedy, his weakest films have most interest measured against what we understand of him.

Published 31 Aug 2016

Kristen Stewart and Jesse Eisenberg lay on the old-school charm in Woody Allen’s Golden Age Hollywood satire.

A comprehensive countdown of the great American writer/director’s complete filmography.