Sometimes, nothing else quite expresses a feeling of confused exasperation than the phrase, “A galaxy of this sucks camel dicks.” Or what about just bleating out, “Brennan’s got a mangina,” or, “Haha, that’s so funny the last time I heard that I fell off my dinosaur”? Films such as Anchorman, Pitch Perfect, and Zoolander spawn irrepressible memories and associations with a particular period of time. It’s almost as if they create instant nostalgia value. Nostalgia for the present.

Adam McKay’s Step Brothers is another such movie. Like so many others, I first watched the film with a bunch of friends after school – all teenage girls bored of petty rules and end-of-year exams. Some had seen it before, some hadn’t. But from that point onwards it invaded the landscape of our daily camaraderie. Our in-jokes were Step Brothers in-jokes.

It’s a film that’s driven by the comedy of neurotic people living in close proximity. It can be watched again and again, and each time new one-liners or alternative scenes will take new prominence. Brennan (Will Ferrell) and Dale (John C Reilly) enjoy a life of sitting at home, drinking beer, playing with machetes, stashing porn and mooching off their parents. However, they find their indulgent lifestyles threatened when their parents marry and they are forced to live together as siblings.

The opening montage tells you almost all you need to know about the state of these man-children. There’s barely a plot, but the film’s willingness to embrace the fact that life isn’t a tale with three acts serves to encapsulate the idle of stasis, of two men trapped in the amber of adolescence. The very fact that it doesn’t rely on exciting tensions, twists or intriguing turns of fate is what makes repeated viewings more rather than less engaging.

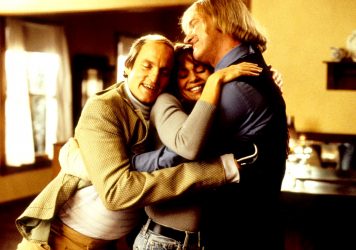

It owes part of its success to Farrell and Reilly’s rude comedic chemistry, already seen in 2006’s Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby, in which Reilly plays the second best teammate to Ferrell’s arrogant NASCAR champion. In Step Brothers, they drag it right to the fore, the pair going head-to-head in a perfectly orchestrated ping-pong match of drum fights and live burials. Brennan and Dale take Peter Pan syndrome to anarchic, R-rated new extremes, applying the defiance of ‘the boy who never grew’ up to sweaty middle-aged men. And it’s all the more hilarious because Reilly is a Serious Actor known for dramas like Magnolia and Gangs of New York.

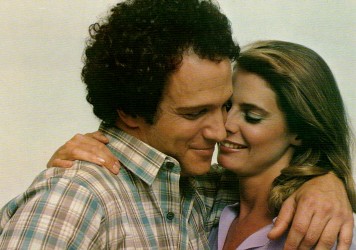

The film’s humour isn’t merely obscene or trashy, nor is it completely untethered from real life. It is all founded on relatable family tensions. The parents offset the ludicrous behaviour as the comic trope of ‘the straight guy’. There’s something very human about Nancy (Mary Steenburgen) and Robert’s (Richard Jenkins) unwavering devotion to their overgrown kids, particularly their constant attempts to not give up on a seemingly hopeless situation.

The animosity between Brennan and his younger brother, Derek, or the strain placed on his parents’ marriage, are all-too recognisable, adding an underlying layer of catharsis to the comic onslaught. Although we all grow up, in the world of Brennan and Dale, what constitutes a ceasefire is realising that you both have the same favourite dinosaur. Wouldn’t it be amazing if all adult conflict could be resolved so easily?

Of its many great sequences, my personal comic centrepiece is when Brennan and Dale build bunk beds to make room for “so many activities”. Their giddy excitement is abruptly cut short when Brennan gets dramatically squashed as the child-size bed collapses under their weight. Dale jumps onto the top bunk saying, “Hey, I forgot to ask, do you like guacamole?” and the whole thing comes crashing down. If you zoom out, the whole film poignantly acknowledges that moment when childish optimism is crushed by the reality of lacking basic carpentry skills.

Like so many other bright-eyed souls, Dale and Brennan decide that music may be their salvation. They set up an international entertainment company by filming an outrageous promotional music video called ‘Boats ‘N Hoes’. But this only causes more drama when they crash Robert’s yacht into a seawall. The film strips back the ridiculous idealism of infantile dreams. It takes recognisable music, offers a tacit connection with the viewer, and then alters perception as the track launches into parody.

The film is full of these comic triggers. Whenever Guns and Roses’ ‘Sweet Child O’ Mine’ comes to mind, it is difficult not to associate the song with Derek bullying his family into a ridiculous Von Trapp-style rendition in the car. Yet, despite all of these unsuccessful endeavours, music is the force that reunites the family in the end, giving Step Brothers that necessary, heartwarming glow. When Dale and Brennan wow the crowd at a Catalina Wine Mixer, its their operative performance of ‘Por Ti Volare’ that becomes the film’s heroic climax.

Today, Step Brothers maintains a bizarre gravitas. Could this be seen as a precursor to the comic book superhero movie? Wide-eyed boys are seen belligerently bickering to a colossal degree before eventually realising their true potential. This macho manchild vs manchild set up stands as a priceless counterpoint to all those exhausting, smash-’em-up blockbusters like Batman V Superman or Captain America: Civil War. But unlike those pseudo-serious epics, when Brennan and Dale eventually become best buds, we actually develop an affinity to all their idiotic behaviour. It takes us back to teenage days, of immature antics between lessons at school.

Published 11 Nov 2016

Ten years ago, the likes of Blades of Glory and Hot Rod signalled the end of the Frat Pack era.

The actor/director’s 1981 rom-com is one of the best films ever made about jealousy and self-loathing.

By James Oddy

The Farrelly brothers’ reached their vulgar, freewheeling peak with this 1996 bowling comedy.