Spend enough time immersed in modern American cinema, and one starts to get the wrong idea about political films. It would appear that to comment on the government would require didacticism, a soapbox, and a sense of gravitas befitting the fate-of-a-nation stakes. In midcentury Yugoslavia, this was not the case.

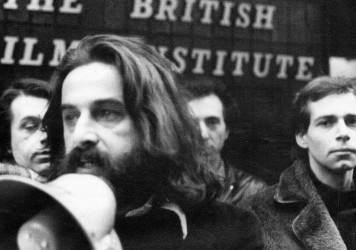

A vibrant, radical, and often bizarre school of filmmaking known as the ‘Black Wave’ sprung from the sociopolitical turbulence of the era, as a new generation of film artists pushed back against state-sponsored oppression with a weaponized offensive of whimsy, surrealism, and subversion. Most prominent among them was Dusan Makavejev, a rabble-rouser with a yen for the silly and provocative in equal measure. He gave the movement a face, an international presence, and in no small part, an identity.

Publications in Bosnia and Serbia have confirmed that Makavejev died early this morning at his home in Belgrade. He was 86 years old.

Born in Belgrade on 13 October, 1932, Makavejev grew up with an innate understanding of how cruel a country could be to its citizens. Life under crypto-fascist dictator Josip Broz Tito, the horrors of the Holocaust, civil wars, mass purges — Makavejev survived it all, and carried the chip on his shoulder into his art.

His films took the powers that be to task, exposing hypocrisy through dark humor and targeted absurdity. His early work in his native Yugoslavia shrugged off the junta’s prescribed doctrine of austerity and repression, suggesting that a good romp in the sack qualifies as an act of protest.

It was there that he made his masterpiece, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, a docu-narrative hybrid forging a daring thesis from Warholian pop detritus, John Wayne impressions, Stalinist propaganda, and masturbation jokes. To this day, it remains startling in its sheer originality and revolutionary spirit.

Makavejev’s ideologies attracted the attention of Yugoslav censors, who banned him from the country for sixteen years. He’d continue to expand his filmography from the safe refuges of Sweden, France, and America, landing another festival-circuit triumph with his merrily obscene Sweet Movie. For his final formal work, he contributed a segment to an omnibus film titled Danish Girls Show Everything, a fittingly horny end to a career steeped in the pleasures of flesh.

Even so, Makavejev will be remembered primarily not as a common horndog, but as a great thinker who understood the potential of erotics to smuggle a more sensitive message to a wider audience. Sex sells, which means sex has to be a necessarily capitalistic enterprise, and it’s in the infinitesimal space between these two ideas that Makavejev set up shop.

Experimental, defiant, and able to command an audience, he should live on as the exemplar for all filmmakers pursuing a political bent.

Published 25 Jan 2019

This messy, invariably entertaining cinematic staple can represent anarchy, revenge and sexual release.

Our latest print edition features guest contributions from Guillermo del Toro, the Safdie brothers and more.

By Sam Thompson

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.