From the post-Vietnam counterculture to brash Reaganite muscle-flexing to Trumpian nationalism, cinema’s ultimate lone survivor has always held a mirror to US society.

sFor a flag-waving icon of American aggression, John Rambo never much liked America. Or aggression, for that matter. Released in 1982, First Blood, the character’s maiden screen outing, shows the one-man army killing just one person – an accident – and originally ended with Rambo being ‘put down’ by his commanding officer. What’s more, the bad guys are Americans, or, more specifically, America itself.

The film tells the story about a traumatised Vietnam veteran neglected by his country and persecuted by the authorities. Made amid the final twitches of American counterculture, First Blood provides a visceral portrait of individual disaffection and national dysfunction. John Rambo may have been a highly trained killing machine but he was also confused, victimised and vulnerable.

Thirty-seven years and three films later, the same character has become an emblem of gun-toting, cigar-chomping jingoism, the oiled-up embodiment of American military muscle. Later this year he’ll be seen riding the frontier on horseback, storming over the border to dispense DIY justice to a gang of Mexican criminals. It’s been quite the transformation. Where did it all go strong?

Well, the signs were there from the start. If Rambo’s plight in First Blood suggested an anti-war sentiment, his climactic speech about returning veterans being spat on by “maggot” hippy protesters at the airport hinted at a conservative heart. And with Ronald Reagan having just been voted into the White House by a landslide, it was the latter that most struck a chord with the American psyche.

Three years later came Rambo: First Blood Part II, a 180-pivot from its predecessor that saluted the fast-changing political climate. As Regan’s “peace through strength” policy saw a 40 per cent rise in defence spending, Hollywood delivered a small canon of steroidal shoot-em-ups whose mission was to restage the Vietnam war with a cathartically favourable conclusion. All these films followed the same basic template – dispatching military troops to foreign lands to fight an alien enemy – though most were done with some degree of proxy.

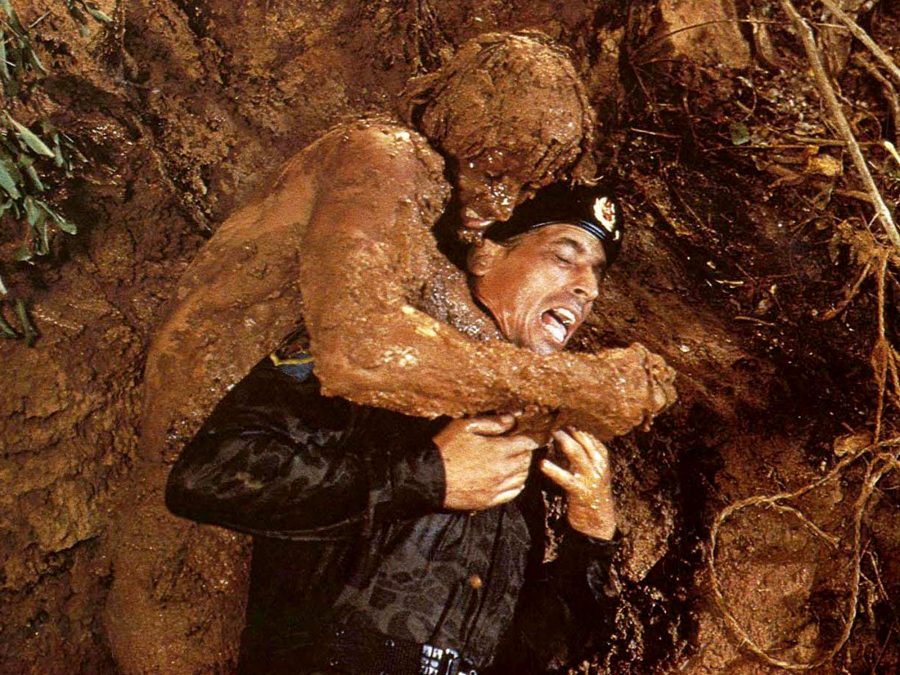

Predator substituted the Viet Kong for a jungle-dwelling extra-terrestrial, while Aliens swapped the jungly tropics for another planet altogether. First Blood Part II, on the other hand, laughed in the face of such subtlety. Rambo’s only question when he’s ordered back to ’Nam to rescue some stranded POWs is a simple one: “Do we get to win this time?”

They did indeed, and that film’s poster shot, of the cartoonishly brawny hero stripped to the waist and wielding a rocket launcher with intent, remains Rambo’s iconic image. The plot also involved the revelation that the POW’s Vietnamese captors were being armed and trained by a nearby gang of Soviets. And so Rambo duly laid waste to two separate factions of communist evildoers, all for the price of one ticket. First Blood Part II became one of the 20 highest grossing movies in history.

Then in 1988, with the second phase of the Cold War reaching its peak and Reagan amping up his rhetoric about the “evil empire” encroaching from the east, came Rambo III. A straightforward franchise extension, the film sees the titular protagonist drafted to the mountains of Afghanistan, where he joins forces with a guerrilla militia to take down the Soviets. It was released a year after Predator and just one month after Jean-Claude Van Damme’s Hollywood debut, Bloodsport. As ever, Rambo III drools over the gleaming torso of its freakishly muscular hero. As he unloaded a small armoury of automatic weapons at anyone with an eastern accent, it was clear that any moral nuance had long since been blasted into oblivion: this was big-screen Reaganism in all its uncut glory.

If Rambo’s rolling with the political times was art imitating life, the man in the Oval Office was only too keen to make it a two-way process. On the release of 39 Americans held in Beirut in July 1985, Reagan joked: “Boy, I saw Rambo last night. I know what to do the next time this happens.” Two months later he vowed to clean up the federal tax system “in the spirit of Rambo”.

But as the decade ticked towards its end, so did Regan’s presidency. He was replaced in the White House the year after the release of Rambo III by George HW Bush. And as ’80s nationalism made way for the cheery prosperity and family values of the ’90s, Hollywood’s action heroes changed accordingly. Out went herculean machismo, in came a goofier, jokier and altogether more charming kind of alpha male saviour in the form Bruce Willis, Nicolas Cage, Keanu Reeves. Arnie went into family comedy mode. Van Damme went straight to video. Rambo went underground.

And that’s where he stayed until 2008, six and a half years into the “war on terror”. The series’ fifth instalment, simply titled Rambo, may have taken a less-is-more approach to its title but every other facet was cranked up to the max. It is the fiercest and most adrenaline-fuelled film in the series to date. And even by the standards of its predecessors, it was startlingly violent. (Four children are killed onscreen; at one stage Rambo tears a man’s throat out with his bare hands.) With 9/11 having ushered in a new age of anxiety, and Bush Jr’s incursions into Afghanistan having reacquainted America with its role as the invasive aggressor, John Rambo was back with a vengeance.

Tellingly, the film’s most pensive moment, a monologue in which Stallone decries the follies of war (“Old men start it, young men fight it, no one wins, everybody in the middle dies, and nobody tells the truth”) was left on the cutting-room floor. Instead, the showpiece line was a bloodied Rambo declaring, “When you’re pushed, killing’s as easy as breathing.” He would know: since his single, unintended victim in First Blood, his kill-count in the sequels had soared to 75, 105 and 254.

That was 11 years ago, and it’s fair to say the world – and America’s place in it – has changed a lot since then. The financial crash rendered a whole new subsection of American society vulnerable and neglected, Russia began flexing its political muscle with intent and the economy that boomed under Reagan started facing new threat. And then there’s the small matter of the country’s new Commander in Chief and the wave of social unrest and disaffection he rode in on. American nationalism is back on the agenda, and it’s taken an unreconstructed and nakedly isolationist tone.

If Donald Trump’s rise has revealed both a politics of lawlessness and an electorate lost in a misty-eyed vision of yesteryear, Last Blood, the fifth and, presumably, final Rambo film, looks well pitched. In the first 30 seconds of the trailer we’re bombarded with images of lever-action rifles, horses galloping around a dusty ranch and our hero gazing across the open range from his rocking chair, all to a rousing country-and-western soundtrack. We’re left in no doubt: Rambo is in the wild west.

Given that the western has long been Hollywood’s way of talking about American imperialism – be it through early tame-the-savages fables or the guilt-plagued moral dramas that later followed – it makes a certain sort of sense that the Make American Great Again era has seen Rambo reinvent himself as a cowboy. And in the wake of the Trump administration’s wall-building vows and with the treatment of Mexican migrants throwing up new traumas each day, Last Blood’s borderlands setting gives the story its customary grounding in the politics of here and now.

Whether all this harking back to bygone eras will see Rambo return to his own introspective, anti-establishment roots remains to be seen. The safe bet would be a straightforward goodies-and-baddies tale – and by the looks of the trailer, the old man’s still an artist with a crossbow. But if he chooses to dust off the machete, lace up his combat boots and take a step into the moral murk, one thing’s for sure: there’s no shortage of it to wade through.

Published 14 Sep 2019

From Commando to Conan, Terminator to Twins, we size up the cultural icon’s ample body of work.

More and more movies are featuring female characters with strength, agency and a drive to take action. What took them so damn long?

Forty years ago, director Michael Cimino set a masterful precedent for coming to terms with the trauma of war in The Deer Hunter.