When we think about the golden age of UK cinema, are we looking at Alfred Hitchcock, Carol Reed and David Lean? Or Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier? The kitchen-sink social realism of Reisz, Richardson, Finney and Schlesinger or Ritchie, Boyle and Curtis and their latter day blockbusters? I would argue none of these, and, that a strong case can be made instead for the rush of youth-oriented productions between 1965 and 1972.

Cinema is a mirror for England and the best films of this period are characterised by a quality, inventiveness and optimism that still resonates decades later. This extraordinary richness owed everything to the colossal success of The Beatles: six hits in the US in 1964 alone and A Hard Day’s Night winding up as one of the biggest films of the year. After this dollars flowed into London as the major Hollywood studios all tried to hit the jackpot. Another factor in creating the zeitgeist of the time was that in 1964-67 UK teenagers had access to 1000 hours of pop music per week, compared to about five hours previously and not that much subsequently until well into the ’80s.

All the participants who flit through ‘Psychedelic Celluloid’ – actors, writers, musicians, cultural movers and shakers of all types – tell much the same story about the impact this made on them: it was a time of full employment, cheap housing and free education: a time when a great deal seemed possible.

The films in turn show this with the way they concentrate on the latest fashions, music, design, clothes and art. While the pop and rock of the ’60s has been the subject of innumerable studies, and people have catalogued the films too, often at great length, up until now no one has put the two together. I began by writing about the career of pop Svengali Ronan O’Rahilly. He produced three films (The Girl on a Motorcycle, Universal Soldier and Gold) and I got drawn in from there. Research showed that that over 300 films and major TV productions of the time had a group, or singer or notable soundtrack as the producers and directors married up the two genres.

Although I wasn’t hanging about in Carnaby Street during the Summer of Love and didn’t see most of these at the time, I caught up with them on TV in the ’80s and ’90s. The current V&A exhibition, ‘You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970’, shows a continued interest in the era but are these films and their music still relevant? I would argue that Performance, The Wicker Man, A Clockwork Orange and Blow-Up will be watched as long as cinema exists. As for ‘relevance’ a number of the more exploratory works still fascinate: feminism certainly doesn’t go out of fashion (Separation, with music by Procol Harum) and neither does absurdism (Work is a 4-Letter Word, with Cilla Black).

How I Won the War (with John Lennon) remains a sharp critique of the English establishment and the transsexual comedy Boy Stroke Girl (with Peter Straker, from the musical ‘Hair’) still feel contemporary having been at least 20-30 years ahead of its time. Let It Be works as the definitive band-in-the-studio documentary and There’s a Girl in My Soup could be set today with its plot of a celebrity chef hooking up with a rock chick 25 years younger than himself. (Anyone for a remake with Steve Coogan in the Peter Sellers role?)

A number of others still work as a historical record of the attitudes of the time: Lindsay Anderson’s Oh Lucky Man! – a kind of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ through the UK of the early ’70s, accompanied by Alan Price and his band – and Bronco Bullfrog (with music by Audience) shows the anti-swinging London world that, after all, existed everywhere else. Leo the Last (with Ram John Holder) is a brilliant, pioneering film that is now rarely seen – despite winning John Boorman a prize at the Cannes Film Festival. A magic realist drama shot in a semi-derelict north Kensington in 1969-70, it’s possibly the first major UK film to portray the emerging black immigrant community in the inner cities.

If any one film represented the era and could be said to be emblematic of the genre it must surely be Blow-Up, which has its 50th anniversary on 18 December, 2016. Made with big studio money it provided MGM with a huge box office hit. It had a big art house director, Michelangelo Antonioni, and a young star, David Hemmings, playing a character with the coolest of occupations – a fashion photographer. With dialogue by Edward Bond, music by Herbie Hancock, the Jimmy Page/Jeff Beck version of The Yardbirds as the requisite pop group and explicit three-way sex (Hemmings with Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills)… what’s not to like? The plot, too, still holds water – the empty futility of celebrity culture mixed with a simple murder mystery. It’s hard to think that anything quite like it could be made that way today.

Simon Matthews is the author of ‘Psychedelic Celluloid: British Pop Music in Film and TV 1965-1974’ published by Oldcastle Books and available 28 October.

Published 11 Oct 2016

A previously lost film provides a fascinating insight into the actor’s unorthodox creative process.

The titan of big screen comedy is at his understated, singular best in Hal Ashby’s tale of a simple-minded gardener.

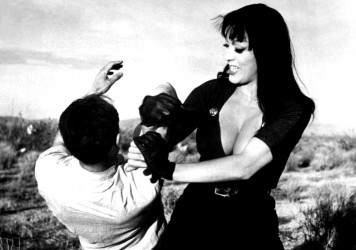

How many ’60s exploitation movies have you seen where women get to smoke, drink, drive and fight?