One of the most striking images in Princess Mononoke is of a life-cycle in microcosm. The deer-shaped god of the forest travels throughout his domain and, with every step, the ground blooms with flowers before they immediately wilt and die away. In the step of the ancient forest spirit lies life and death, held in balance. As director Hayao Miyazaki’s dazzling fantasy celebrates its 20th anniversary, its preoccupation with this delicate balance feels freshly urgent.

Balance is the watchword from the film’s first frame. The opening text speaks of a time when the world was covered in forests and humans lived in harmony with the spirits. That time is over, as human greed is encroaching on the forest and waging a war with the spirits. The scene that follows shows the result of that war, as a writhing, blood clot-tentacled demon ravages the landscape. The world has been thrown out of balance and nature is suffering. Yet Miyazaki refuses to be didactic; this is not anime’s answer to An Inconvenient Truth.

Princess Mononoke encapsulates several different Miyazaki tropes, from strong heroines to a soaring Joe Hisaishi score. Nowhere is this film more Miyazaki, however, than in its moral shades of grey (where American animation tends to think in black and white). There are no bad guys in Princess Mononoke, just several competing groups of equally murky morality. Lady Eboshi, by all rights, should be the villain – she is leading the charge against the forest spirits and exploiting the landscape to expand her industry. Yet she also leads a socialist collective within her fortress, where freed slaves and lepers help to run the place, while her agenda is almost explicitly feminist as she empowers women to run the show; hardly villainous traits.

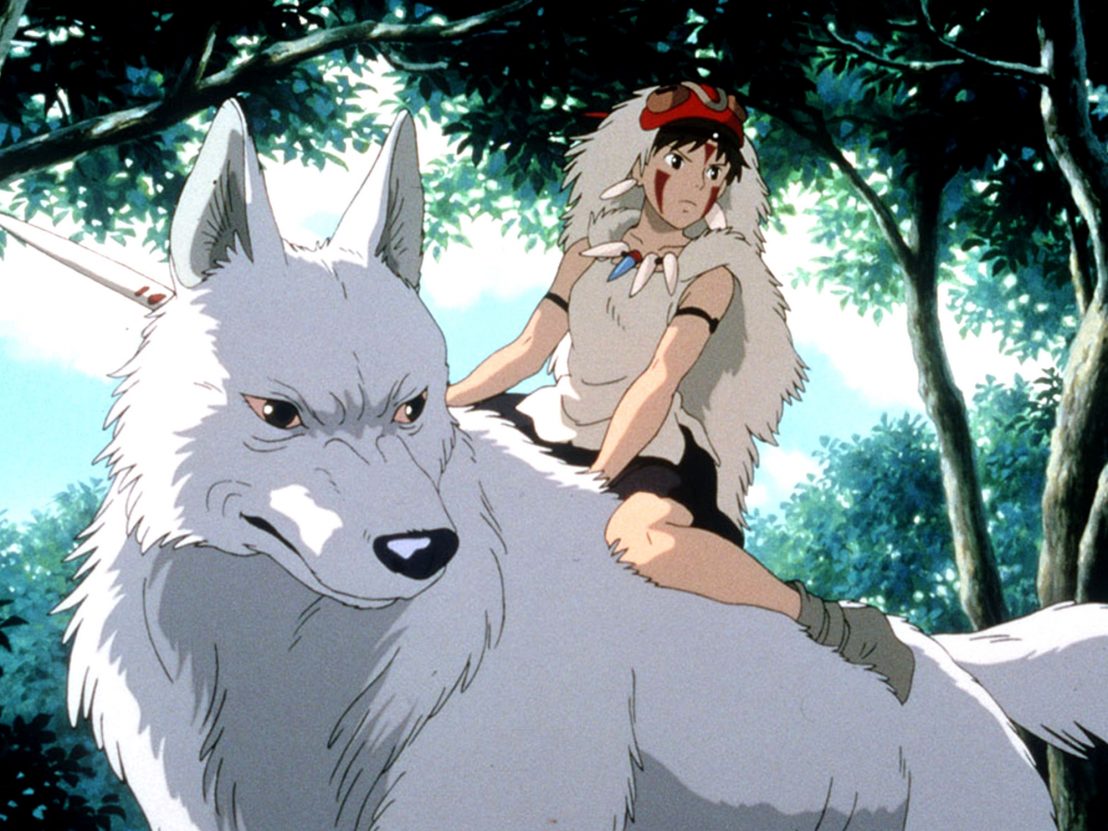

Then there is Mononoke herself, a fearsome, passionate and complex heroine who we first meet wiping blood off her mouth and she sucks the bullet out of a wolf god. She is the defender of the old ways, an advocate for spirituality and nature, yet she is also quick to violence and thirsts for revenge. At one point, a character asks of Ashitaka “whose side is he on?” and the question applies equally to Miyazaki. The danger lies in embracing extremes where a middle path can exist.

One thing, however, is clear: Miyazaki urges his viewers never to lose their reverence of spirituality and nature. His frames mingle awe with intimacy. Grey and black human developments are constantly dwarfed by masses of dappled green, forests and hills covering the image in a morass of detail. Yet even in a world where gigantic boar-deities succumb to eldritch demons and explosive wars take place on hillsides, Miyazaki still creates a space for tranquil spirituality. He revels in small details, like a canopy of smiling Kodama spirits enjoying the sensation of swaying in the wind.

Like the footprints of a forest-god that cause a small cycle of life, death and life again, Princess Mononoke exists in a state of perfect balance. The viewer is left with the impression of a wise, ageing director looking at the world with a sense of contented detachment. Far from trying to bend the viewers to his will, he presents a world of spirits and soldiers, gods and men, progress and tradition, while envisioning a world where all can coexist. In an era where nuance and balance die daily on the internet, we would do well to catch on to his vision.

Published 11 Jun 2017

In the mid ’80s, the anime stable was struggling following back-to-back box office flops. All that changed with the arrival of a young witch.

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.

By Beth Webb

How this great grey tree-dweller became the Studio Ghibli co-founder’s most beloved creation.