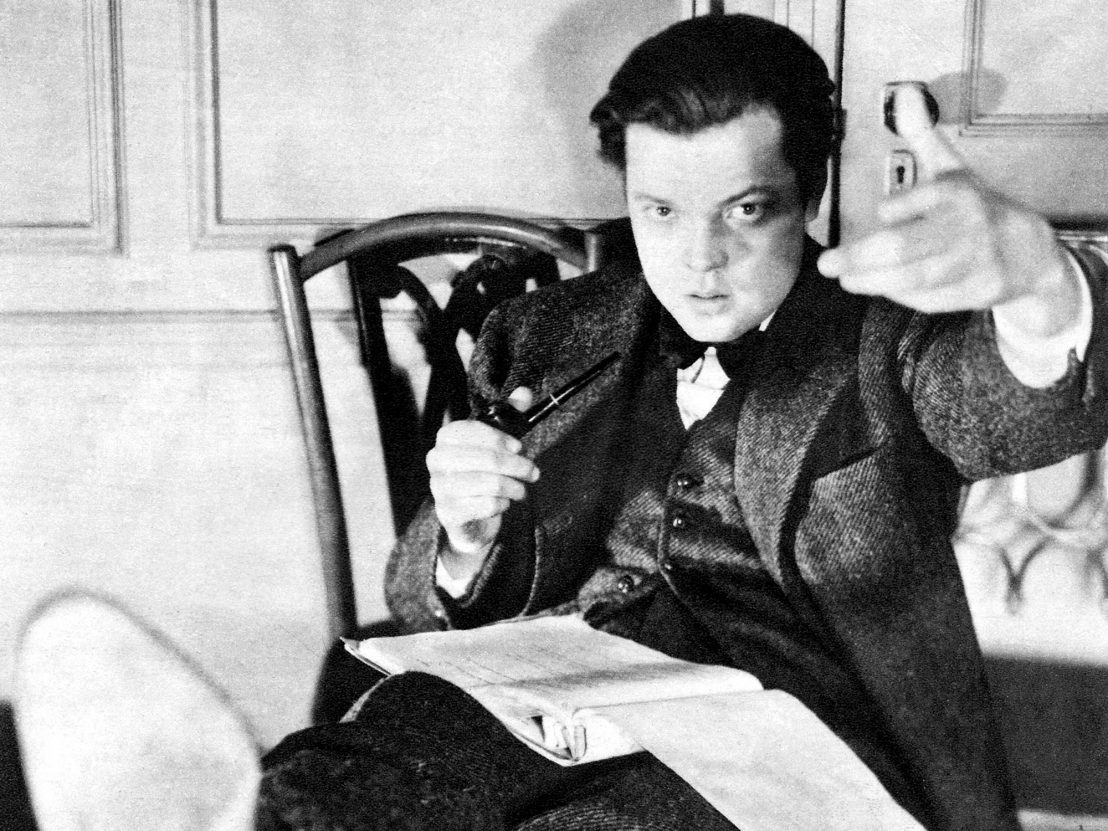

Fifteen years after the release of Citizen Kane, Orson Welles’ Hollywood career was stalling. A 1948 production of Macbeth written, directed by and starring Welles was a commercial flop. A 1955 film Mr Arkadin, released under two different names and in seven different versions, was named by Welles as the “biggest disaster” of his life.

Touch of Evil was billed as a comeback. A cop drama set on the Mexican border, with Charlton Heston (in blackface, no less) in the lead role and Welles himself as his foil, the film was supposed to sweep Hollywood off its feet and kickstart Welles-mania all over again.

Instead, it was released as a B-movie in a double feature, billed below Henry Keller’s The Female Animal. The rough cut that Welles delivered to Universal was substantially changed and re-edited. Additional footage was shot under a new director – Keller, of all people. If ever you’ve ever felt bad for the David and Goliath plight of today’s blockbuster directors, then spare a thought for Welles, who was banned from the editing suite entirely.

The exact reasons for the fracas are murky, though Welles had a habit of letting the editing process drag on – Touch of Evil’s rough cut took over three months, and he told Cahier du Cinema in 1958 that he could “work forever” in the cutting room. It’s easy to see how he might provoke a studio’s ire.

True to form, Welles came out swinging. Five months after first receiving the rough cut, Universal received a 58-page typed memo, addressed to the studio’s Vice President, that took apart the final product of Touch of Evil, scene by scene and shot by shot.

The memo is a withering rebuttal that attests to both Welles’ personal devotion and the scale of attention he gave to every aspect of his work. “The original editing of this particular little section was really quite effective and I honestly can’t see what, from any point of view, has been accomplished by tearing it up and re-building it in this form,” he writes of the decision to add a three-word line back into the opening scene. “In terms of clarity, nothing is gained; considerable excitement has been lost and an unpleasant line (which I regret having written) has been put back in.”

Welles picks up on everything from lighting adjustments to changes in the sound diegesis. His systematic take-down might seem petty and self-important, were it not for the convincing lengths he goes to justify each complaint. The height of his knit-picking comes in the face of corrupted continuity. He describes a shot where his own character, Hank Quinlan, is “looking in one direction and then almost immediately in the other.” He also writes that “the second direction is the correct one and prepares for his rise from the chair.” And with tongue-biting self-restraint he concludes: “It should certainly be fixed.”

Of one particular attempt to splice unconnected footage, Welles writes “the welding of these two parts has been managed with as much skill as the resources in actual film made possible, and I congratulate whoever made the attempt. It remains, however, just that: an attempt.” Not yet sated, he twists the knife by returning a criticism clearly levelled at himself in the past: “The sort of editing it was necessary to resort to in the attempt to force these two parts of a sequence into the form of a single scene can only be described in the same way: it is simply not ‘commercial’.”

The memo ends with the earnest plea “that you consent to this brief visual pattern to which I gave so many long days of work.”

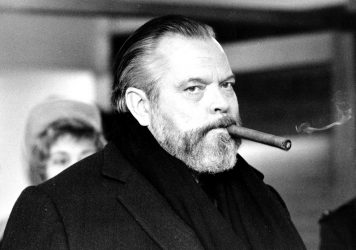

So detailed and so exasperated were his notes that in 1998 a new version of Touch of Evil was released, re-edited in accordance with Welles’ wishes. The restoration was supported by Universal and removed as much of the additional footage as possible. The opening sequence was restored to its original glory, without tracking credits overlaid. It’s now regarded as one of the greatest in all of cinema.

Studio influence is a hallmark of our times. It’s an inevitable feature of big budget filmmaking captured so chillingly and comedically in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, by the faceless echelons of Hollywood who try to crowbar an unknown actress into Adam Kesher’s picture without explanation.

The comparisons between Welles’ plight on Touch of Evil and those of various contemporary filmmakers draw themselves. Though it’s unlikely we’ll be treated to a director’s cut of David Ayer’s much-maligned Suicide Squad in 2056, Welles’ fantastically feisty memo, and the timeless masterpiece it eventually spawned, serves as a handy reminder of the virtues of stubbornness.

Published 15 Jun 2017

By Jack Godwin

The Other Side of the Wind is finally being completed and could be available to stream this year.

For his final trick, Orson Welles will deliver a fruity, funny film essay. And astonishing it is too!

By Tom Graham

Read the remarkable story of the director’s ill-fated passion project, 400 years on from the death of Miguel de Cervantes.