A man stands on the edge of a dance floor, his face hard to read. Electronic dance music and haze fill the space and bodies shimmy and twist around him, but the man is very much alone. There are many of these scenes in Ron Peck’s 1978 drama, Nighthawks, often cited as Britain’s first overtly gay film. The man is Jim, played by Ken Robertson in his only major film role.

Queer history often brings to mind passionate fights for justice, colourful Pride parades and a fierce determination for visibility, but this version of history feels far removed from Nighthawks’ world. Although gay sex had been legalised a decade earlier, British society had little tolerance for LGBTQ+ lives in the 1970s. As one character puts it, “[We’re] not even human as far as they’re concerned.” Vilified by the government and thought to be living out deviant lifestyles at the fringes of society, Peck wanted to show the truth: that gay men are not outliers of British life, but integrated within all facets of society, living out painfully banal lives just like everyone else in ’70s London.

It is therefore crucial that Jim isn’t an activist or revolutionary. Instead, he’s a geography teacher, seemingly content in his disciplined life which is divided between two worlds. By day he teaches and socialises with friends; by night he loiters around gay clubs hoping to spark a sexual connection with someone. Even his one-night stands are repetitive: same conversation (“Where are you from? When did you move to London? Do your flatmates know you’re gay?”); the same offer to drive his companion home in the morning and the same non-committal vagueness to stay in touch.

The repetition of Nighthawks’ structure is often perceived as a flaw in the film – as is the dullness of Jim’s life – but Peck isn’t interested in the kind of melodramatic tragedy that for a long period underpinned queer cinema. Rather, this is a candid portrait of gay life pre-AIDS, one which shows the reality of living in a hostile society. For Jim, the small, dingy club he frequents is a sanctuary. A place where he can be himself.

You might not notice it at first (in the club scenes, Jim keeps to the walls, eyes darting around the dance floor), but while physically he appears as restrained as in his closeted day-to-day life, he is emotionally liberated here. In one sequence, Peck pushes the camera in, moving closer and closer to Robertson’s face until it fills the screen. A mixture of emotions are there: the loneliness of living between two worlds, the desperation of his search to make a connection and the fear of not finding someone to go home with.

Peck was adamant that his protagonist should be an everyman, not someone living their life in the margins. Near the end of the film, Jim’s two lives finally bleed into each other and he’s confronted by his students, who ask him bluntly, “Are you bent? Are you queer?” Peck puts us in Jim’s shoes as he responds to the barrage of questions patiently and compassionately. Instead of reinforcing a ‘them against us’ mentality, Jim has a frank conversation about his sexuality and life. It’s the first time we really see him open up and trust other people.

Although Nighthawks left an impression on a whole generation of LGBTQ+ people, its wider reputation has suffered due to the misconception that it is a dull film about a dull man. Watching it in 2020, however, a lifetime removed from its setting, the film’s message still resonates thanks to Robertson’s performance. The loneliness of living two lives, his aching search for companionship and uncertainty about who he can trust – these are feelings that every LGBTQ+ person will be able to relate to.

Nighthawks is currently available to stream on BFI Player.

Published 5 Apr 2020

Céline Sciamma’s 18th-century romance beautifully portrays the hiddenness of same-sex relationships.

By Luís Azevedo

Lesser-known works that broke the mould, from Kenneth Macpherson’s Borderline to Sally Potter’s Orlando.

By Sam Thompson

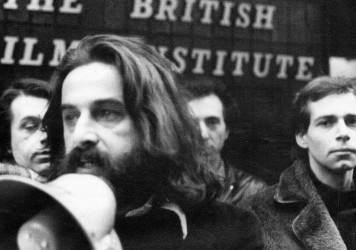

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.