Managing expectations for a film can be difficult, especially where genre cinema is concerned. Even before you sit down to watch a horror movie, for instance, it’s typical to anticipate being frightened or at least provoked into some kind of visceral reaction. Rarely do you see horror effectively utilising new techniques in order to scare viewers.

Consider the jump scare, an all-too familiar trick that seldom fails to deliver. Its power to manipulate and hold the attention of the audience is an art in itself, which when perfected can be audacious and deeply disturbing. In Mulholland Drive, director David Lynch inverts this method to craft a scene that is so confident in its ability to terrify us that it actually lays out precisely how it will do so.

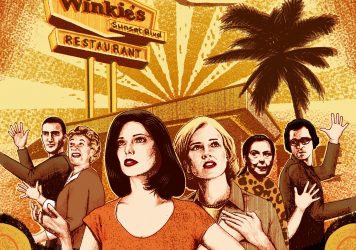

Eleven minutes into the film, we enter the fictional Winkie’s Diner on Sunset Boulevard. Two men are sat opposite each other at a table. There is nothing particularly notable about the inside of the diner. It is almost completely unremarkable. Why are we here? These men have not featured in earlier scenes. All we have seen so far is a jitterbug competition and a car crash that traumatised one victim so badly that she had to seek refuge in a nearby house. Is this scene part of that story? As viewers, we are left confused and on edge – but the mystery at hand is already working its magic.

Dan and Herb (played by Patrick Fischler and Michael Cooke), are noticeably different in their body language. Dan is anxious, uptight and possibly sleep deprived. By contrast Herb is relaxed and confident. Dan tells Herb why they are here. He has had the same dream about this place, this very diner, on two separate occasions. Both men are present in this seemingly mundane vision and both are scared beyond belief.

The cause of their fear is the presence of a man behind the building, who Dan can see through the wall. He says he never wants to see that man’s face outside of a dream but stops short of describing his tormentor’s features. Herb initially cracks a joke but becomes more intrigued as the story progresses. Upon its conclusion, he decides that they should both go outside and see if the man is actually there.

It is made clear that all this is not taking pace inside a dream, so there is little chance that the man is behind the diner. And yet everything about this scene suggests that it is indeed a dream. The camera is shaky, barely staying still and carelessly roaming up and down and behind the two characters. Despite the fact that we are in a busy diner in the middle of the day, the only discernible sound is of the men’s voices. There is no noise coming from the kitchen, the other customers or the street outside. The tension is palpable and increases further when they exit to investigate whether or not something wicked lies in wait. Perhaps this is the dream.

This is a jump scare par excellence – unlike any other in the history of cinema. It takes place in broad daylight in an urban environment. Lynch turns this seemingly safe space into a nightmare scenario where nothing is certain and danger lurks just around the corner. For his part, Fischler conveys more terror in five minutes than most actors manage over the entire course of their careers. He is sweating and short of breath throughout. When he finally approaches the rear of the diner, he moves tentatively, rigidly.

His fear of what is about to come combined with the atmosphere of the scene create a truly mesmerising piece of cinema that works despite the climax having already been spoiled just moments before. It almost doesn’t matter if the man is actually behind Winkie’s or not. The sense of dread that this scene engenders is so intoxicating that it perseveres for the proceeding two-and-a-half hours.

In Mulholland Drive, we are told to expect one thing but choose instead to believe something else. This thread runs right through the film, from the audition scene to Club Silencio, where everything has already been described in detail yet in the moment we are fully engrossed nonetheless. The way that Lynch constructs each scene in the film is extraordinary, but it is Winkie’s Diner which shows the director at his most blatant and manipulative best. As viewers we are conditioned to anticipate what comes next, but just when we think we’ve got the answers, Lynch changes the questions and stills gets results.

Published 8 Apr 2017

The cult director’s peek behind the curtain of this iconic American city reveals the horrors within.

By Adam Nayman

Is David Lynch’s warped Tinseltown satire from 2001 a contemporary riff on one of Hollywood’s classic-era staples?

The cast and crew of Twin Peaks remember the making and breaking of a cultural phenomenon.