When Michael Radford began production on 1984, the surveillance state in which we now live had only just begun. But like George Orwell’s source novel, the film remains timeless: it reflects all the atrocities of the past, present and future onto the reader.

Choosing to make 1984 in the year 1984 was no gimmick, but an inspired decision by a filmmaker working at the height of Thatcherism, and before London was gentrified beyond recognition. Radford was able to find locations that were barely standing, easily doubling for bombed-out landscapes.

The timing also linked the film indelibly with how the digital age successfully sold the public slavery through promises of freedom: 1984 also marked the release of the first Apple computer, an event promoted with a Ridley Scott-directed advert also inspired by Orwell’s novel.

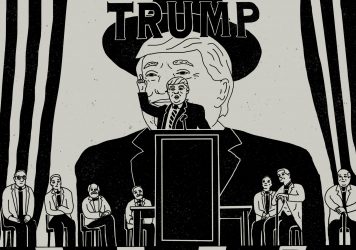

With the recent passing of lead actor John Hurt and the swearing-in of Donald Trump as President of the United States, both 1984 the film and novel have returned to the forefront of popular discourse, as well as the bestseller list. Here, Radford talks candidly about his memories of working with Hurt, and what it means when the Two Minutes Hate can be telescoped into a Twitterstorm.

LWLies: John Hurt was supposedly your first and only choice for the part of Winston Smith. What made you choose him?

Radford: I bumped into John Hurt at some awards thing. I just went up to him and said, ‘Look, would you play Winston Smith in 1984? And by the way, if you don’t want to do it, I won’t make the film.’ And I actually meant it. It’s the kind of thing you wouldn’t say now, but I did at that time. I only did that once again, with Il Postino with Philippe Noiret. Hurt ended up just saying yes, and that’s how we met.

What do you feel he brought to the role?

He was just perfect for the part. He was the person who had to play Winston Smith. He was so scrawny in those days and so unhealthy looking. At the same time, he had that sort of desperate look in his eyes. And he was a good actor.

Was there a certain film or performance that caught your eye?

In my mind he had always stuck out, from the moment he played Richie Rich in A Man for All Seasons. He had this extraordinary quality. I can’t explain what it was… he was just such a good actor, such a presence, even though this part he had was really quite small. He just stole the film and I think that’s what made him film-famous. We made another film together, White Mischief. We became great friends for a long time, until he got married again and lived somewhere else – he went to live in Kenya for a bit. I think everybody thought it was mistake, but he didn’t realise that till a couple years later.

Doing you have any interesting memories from the making of 1984?

Despite being a film actor, he had a very theatrical voice and a great, strong presence, but he had a slightly tendency to over-act. He claimed I once said to him, ‘John, you are an incredibly talented actor, but for this movie I need only 10 per cent of that talent’ – which was a polite way of saying ‘stop over-acting’ – but I don’t remember saying it. He was incredibly athletic, I remember that. We laid a track down… we didn’t have Steadicams in those days. You didn’t have visual effects, so I had to blow up a house in the middle of him walking by this camera track. He had to cross the track, which was built up so it was nearly thigh height, and he was able to keep the same face and step over the track without his upper torso showing he had altered height. I was very impressed by that.

The other film people always think of is The Elephant Man.

I used to tease him that he would only be recognised in Japan if he got off the aircraft with a bag over his head. He was fantastic in that, and I wanted him to be in this new version of King Lear, but sadly I’ve missed that… I miss him.

What was your favourite film role of his, other than 1984?

Apart from A Man for All Seasons, he was pretty good as Steven Ward [in Scandal]. He has this wonderfully open, vulnerable face. It’s so surprising that he’s gone. I hadn’t seen him for a while, he got married again and I was a little tired of trying to keep up with who he is married to and what he was doing and all the rest of it. I spoke to him a about doing King Lear, but he was a bit pissed off: I think he wanted to play King Lear himself. He would’ve been good, but unfortunately Al Pacino is bigger box-office. The best thing about making films in 1984 was you could actually almost choose who you wanted, as long as they were somewhere in the public eye.

Richard Burton must have been interesting on the set as well…

He was living in Haiti at the time and actually wasn’t my first choice – that was Paul Schofield. He broke his leg, and then I looked at Alan Bates, then Marlon Brando was going do it for a bit, but we couldn’t afford him. He wanted something like a million quid and we had £80,000 so he didn’t want to do it. We went to Rod Steiger, who had just had a facelift. In fact, we got a telegram from his agent: ‘Unfortunately Mr Steiger won’t be able to do this film because his facelift has fallen.’ I’m glad we didn’t have him, because he was a real beast.

Everyone was scared of Richard Burton, because he was reported to be a drunk and very badly behaved. I also did something you could never do these days, I cast him six weeks into the shoot. We were shooting the film without having cast one of the main roles. He was fantastic. I had never met an actor like him, he really was a one-off. He and John gave up drinking during the making of the film, which was great. I think they went on a bender as soon as we finished. Sadly, Richard started again as soon as it finished, and it finished him off. He was only 58. It was incredible, he looked like an old man.

He really didn’t have any psychological input into his characters, he just had this fantastic voice, which he could modulate. He could read a telephone directory and make it sound like Shakespeare. It was a fantastic experience, and I became the go-to director for science fiction for a while after that. I was offered RoboCop, which I turned down – I couldn’t understand it. That was a bit of mistake, actually.

That would have been different take…

I thought it was sort of a third-rate version of The Terminator. It wasn’t really, it was something else. Orion Pictures flew me out to LA, and [producer] Mike Medavoy said, ‘If you like it, you start on Monday!’ And I thought, ‘holy shit, this must happen to everybody. Well, I’ll see if I like it.’ They were persuading me to do it, but by the end of the weekend I realised I just couldn’t do it. It was a pity, I thought I was doing the right thing because I really wanted to be a European director and not a American one. With time I’ve come to see it as a major stumbling block in my career. I could’ve gone on and made a huge amount of money!

You could have been Paul Verhoeven! Did you feel any competitiveness with Terry Gilliam, whose Brazil was in production at the same time using some of the same locations and crew?

No really. The funny thing was, we used the same location scouts. I found myself following Gilliam around, going to the same locations. We shot ours at a place called Beckton Gas Works, where they’d pulled the structural steel rods out of the reinforced concrete buildings. Strangely, it left the place still standing but kind of tottering about, so it looked like the place had been just hit by a nuclear blast. Even though I got prizes for visual effects, there are no visual effects in the film. It was all shot for real which gives it a certain quality, and it hasn’t dated in terms of its effects.

There’s a scene which today would most certainly be done with visual effects, with John Hurt shaving and this helicopter with black windows rising up and observing him shaving through the window. That was done for real, with a real helicopter. The telescreens were all back projection, which made it really difficult because we couldn’t put the stuff on the telescreen afterwards so you had to be really careful about how you cut things for backwards and forwards, because it had to match.

What do you think the film and the book have to say about current events and the future?

‘Alternative facts.’ I actually did a film last year for a Japanese television company thing called WOWOW about surveillance. The difference between surveillance in 1984 and today is they want to do it secretly, and in 1984 they made you aware you were under surveillance. That’s what scared everybody. The thing about 1984 is it’s a kind of Greek myth, it collects all of the pieces of tyranny. The book was more about left-wing tyranny and the film is about tyranny on both the left and right. Nothing I recreated in the film wasn’t going on in the real world in 1984, I took a lot of it from documentary footage of executions and repression from all around the place.

[Composer] Dominic Muldowney said: ‘Have you noticed that all fascist right-wing national anthems are in a major key and all communist ones are in the minor key?’ And it’s true. There is a reason to that, fascism was all about physical repression, and left-wing totalitarianism was about crushing the spirit, if you like. It was all about making people feel guilty about themselves, making people believe they were traitors. You didn’t have make anybody believe anybody was a traitor in a fascist society, you just kicked them to death.

Another thing I learned was that although Orwell invented the concept of the telescreen, he had no idea of its power. He knew television was the new thing, but he underestimated its power. In his mind telescreens were kind of like gigantic radios with pictures. When we put them on the set – and some were 20ft high – the effect they had on people just blew everything else away. Nobody looked at the posters or listened to the radio, the telescreen just dominated everything.

I shot a propaganda film, which I based on one written by Dylan Thomas during the war. We did this to the crowd of 2000 people in the opening scene of the Two Minutes Hate. All we had was a leader, a national anthem and a salute, and we shot about five or six takes and about 15 or 20 people fainted. Something about the rhythm of it triggers something in people’s minds.

What do think of the parallels to Donald Trump?

Well, Trump is a old-fashioned dictator: Hitler was elected to power, so was Putin. He just appeals to the knock-them-down, kill-them-dead theory of politics. People feel powerless. Every so often when things happen in the world, people want a guy who is confident. He’s very believable when he says things people want to hear, and it’s really the reason why Clinton lost. She lost because she’s not warm enough, you never got the sense she was doing things for other people, she was just doing things for herself. It’s also why Bernie or Elizabeth Warren would’ve been better choices.

Where do you stand on the notion that Julia was a member of the Thought Police?

I don’t think she is a member of the Thought Police at all. I think she’s actually the only non-political person in the whole thing. Winston wants to learn, and it’s one of the things I changed from the book. She doesn’t go and see O’Brien, it’s him who goes to her. She represents the real freedom, which is the freedom to be. It’s very much a repressed public schoolboy’s vision of the school matron, which is what she was in terms of Orwell’s fantasies. I kind of love her for her kind of carelessness. I scoured the book for all sorts of undercurrents, and I think it’s wrong.

What are you working on now?

A biopic about Andrea Bocelli, who is the biggest selling recording artist in the entire world as we speak. He’s the blind tenor. It’s quite an interesting story and a challenge. He’s amazing and I’ve learned more about blind people than I ever expected to. Antonio Banderas plays the musical maestro who gets Bocelli back on his feet after he hits the bottom, thinking he will never get anywhere and won’t be able to sing. King Lear is after that, and it all depends on Al Pacino, but that should be coming up soon. That’s my hope, because he would be really great.

Published 13 Feb 2017

The man with the huskiest voice in showbiz is sadly passed, leaving behind a body of astonishing work.

Movies have always reflected social attitudes and trends – and that could prove especially vital over the next four years.

By Thomas Hobbs

The director’s satirical 1994 horror explores what happens when society embraces its worst monsters.