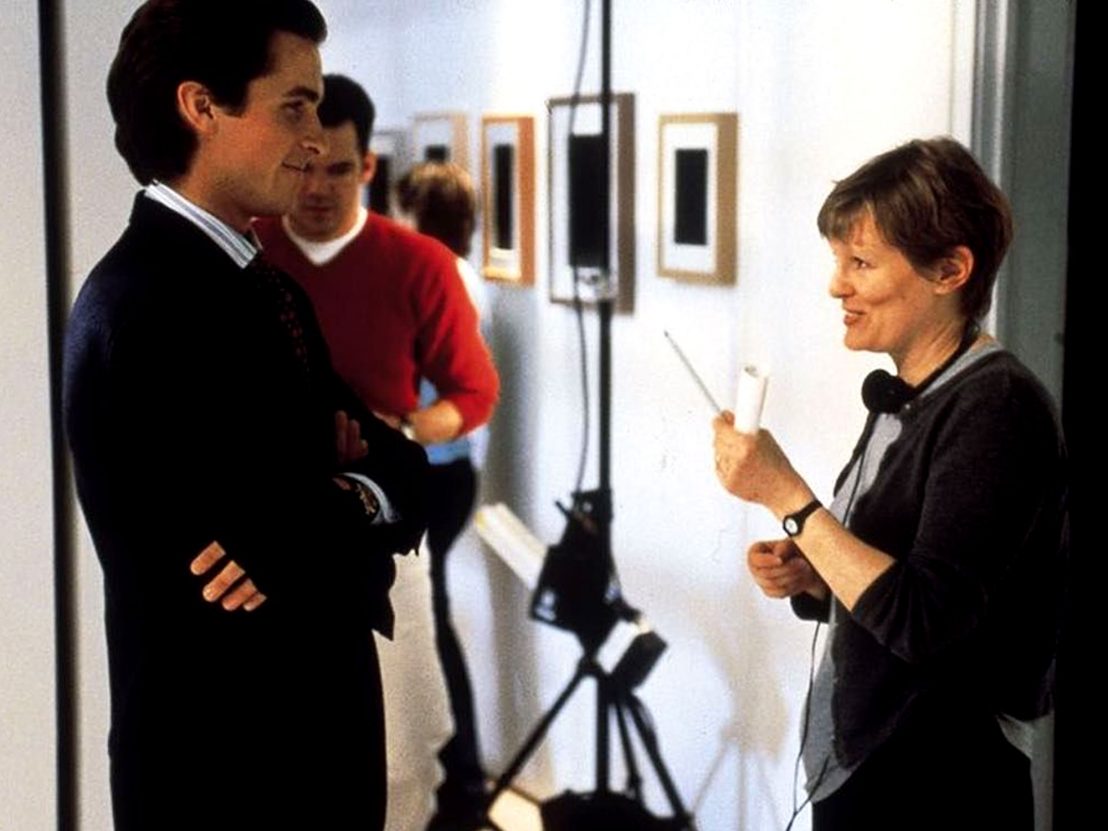

The director reflects on the creation of one of cinema’s enduring monsters, Patrick Bateman.

“The one thing you couldn’t do was think Bateman was in any way cool,” director Mary Harron tells LWLies, discussing the making of her seminal psychological thriller American Psycho. It was two decades ago this month that audiences were introduced to Christian Bale’s grinning terror, lifted from Bret Easton Ellis’ scabrous satire of ’80s capitalist greed and toxic masculinity.

Just four years earlier, Harron was lost in the life of radical feminist Valerie Solanas and her quest to kill an iconic artist in 1996’s I Shot Andy Warhol. Cut to 2000 and she was back on controversial ground, this time switching gears to examine unchecked male rage through a much-needed a female lens. But while American Psycho’s appeal has endured, according to Harron, Bateman’s fate was never clear.

“I knew the material was so strong and controversial there was no way to do anything safe with it,” says Harron. “The danger factor appealed to me. I also felt that the book had been misunderstood. When I started reading it I thought ‘Oh, this is actually really funny.’ Obviously there’s extreme violence in it – but there’s also a satirical side that no one was talking about. I felt like the best parts had been overlooked. I had no idea whether it would work as a movie but I told the producer, ‘If you pay me to write a script, I’ll have a go.’”

With the commission secured, Harron began adapting Ellis’ text with her writing partner Guinevere Turner. One of their aims was to bring out more of the humour. “One thing I liked about the novel,” Harron remembers, “was the way it presented the character; there were a lot of scenes where he was kind of a buffoon. The book does critique male behaviour, but when Guinevere and I were reading those scenes we were like, ‘Okay, that’s enough of that.’ A little goes a long way.

Harron continues, “Bret himself is gay and it was obvious to us that he was not presenting a traditional expression of masculinity. He was offering an outsider critique of it, just as we were. In that way I think we all had the same sensibility. Maybe Bret found Bateman to be cooler than we did. Sometimes there’s self-identification in the book, sometimes he’s being satirical. That makes Bateman very slippery, complicated and interesting.”

“Christian Bale’s physical preparation was beyond what I expected”

One tweak Harron and Turner made was the addition of Willem Dafoe’s Detective Donald Kimball, who not only added tension but ensured that viewers were left ambushed by the chilling disparity of Bateman’s world. “I wanted to go from a scene of social satire – Bateman and his fiancé at lunch, where it’s funny – to something extremely horrifically violent and there’s no preparation for it,” Harron reflects. “I wanted to capture that sense of lurching back and forth between these daytime and nighttime worlds.”

Then disaster struck. Despite Bale being Harron’s first choice for Bateman, production was placed on hold when a fresh-from-Titanic Leonardo DiCaprio expressed an interest in the role. “I didn’t agree with that,” says Harron, “partly because he was such a big star but also because he had a teenage girl fanbase. I just didn’t think he was right for it – so I was fired from the movie for a while.” It was only when DiCaprio’s Oliver Stone-helmed vision for American Psycho fell apart that Harron was rehired. “They couldn’t agree on the script, so they brought me back and I was able to cast Christian.”

From that point on, Bale threw himself head first into the role, becoming Patrick Bateman before Harron’seyes. “His physical preparation was beyond what I expected,” she admits. “I thought he might have to visit the gym, because Bateman works out, but he went through a complete physical transformation. He only ate grilled chicken.”

Harron also reveals that she saw Bateman as someone stripped down to their primal urges. “It’s more like a monster movie; you have someone who is almost a deformed human being, who doesn’t have normal instincts and is filled with terror and rage. How do they operate in the world? It was almost like someone from another planet trying to fit in on Earth. We talked about it from that point of view.”

Using this as their starting point, Harron and Bale constructed their portrait of a serial killer bit by bit, while still leaving room for improvisation. “I remember Christian saying, ‘I think I’m going to Moonwalk’,” says Harron, referring to one the film’s most memorable scenes, the death of Bateman’s rival Paul Allen, played by a yuppied-up Jared Leto. Set to the upbeat Huey Lewis and the News hit ‘Hip to Be Square’, this sequence brings another key aspect of the film to the fore: its ironically peppy soundtrack.

“It was really hard to get the rights for the music,” says Harron, “because we couldn’t find anything that worked as well as the music mentioned in the book. It had to be glossy, mainstream pop. The more happy the music was, the better it worked. ‘Walking on Sunshine’ worked really well when Bateman is walking into his office. It had to be American and it had to be upbeat.”

Despite its reputation today, American Psycho initially divided opinion. “People didn’t know how to take it,” Harron recalls. “We did test screenings and it split people down the middle; it inspired very strong reactions.” Coming off the back of the more overtly feminist I Shot Andy Warhol, some viewers saw Harron’s latest as contradictory, based purely on Bateman’s treatment of his (often female) victims.

Very quickly, the film’s violence overshadowed any nuance in the story that Harron had hoped to highlight. “There’s really not a great deal of violence in it, but everyone was so outraged. People didn’t know when it was supposed to be funny, when it was okay to laugh. They thought it was just a violent slasher. I thought Christian would get nominated for something because his performance was so great but it didn’t happen. In a lot of ways it launched him into a new phase of his career, but the real discovery of the film happened gradually.”

Since its initial release, American Psycho has seeped its way into pop-culture, more recently birthing a wave of tongue-in-cheek memes. In many ways, it feels more relevant now than ever. “The whole Bateman attitude of Wall Street and the one per cent – the injustice today seems much worse,” suggests Harron. “Whenever I film a TV show, somebody always comes up and tells me how much they loved American Psycho. I’m surprised by the intensity of people’s reaction to it. People tell me they’ve seen it 30 times – I haven’t even seen it 30 times! It seems to have touched a nerve, and it’s nice that people are still watching it.”

Published 14 Apr 2020

By Tom Williams

Bret Easton Ellis and Mary Harron’s caustic vision of ’80s consumerism is sadly back en vogue.

Read part one of our countdown celebrating the greatest female artists in the film industry.

By Simon Bland

The writer/director reflects on the making of her cherished Tokyo love story.