He was an abusive and tempestuous artist, but the emotional power of the late German director’s tragic melodramas is undeniable.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is a hellish wonderland. To be fascinated by him is to tumble down a theatrical, dryly comic rabbit hole into a society where cinematic passions rule and good behaviour has no currency. The headline facts about the prolific New German Cinema director are dense with intrigue. There was his untimely death at 37 (from a cocktail of cocaine and sleeping pills), the way he was found (still clutching a cigarette), the number of filmed works (44), his lovers (countless men and women), his great loves (three men) his abuses (drugs, alcohol, food, people) and, stringing all together, a seer’s ability to atone for his bleakest deeds by creating films shot through with emotional integrity.

It’s easy to get lost in the shadowy byways of mythology surrounding this great and controversial director. For salacious reasons, sure, but also because Fassbinder’s life and art overlapped so much that understanding one enhances understanding of the other. The urge to play detective, linking film to life, extends to those described by biographer Robert Katz as “Fassbinder’s people” – those who loved, lived with, and worked for him in one communal mass of creative and emotional energy.

Actors usually disappear by playing characters. Fassbinder’s people – who acted across multiple films – were exposed. He did not spare his own mother, Lilo Pempeit (real name Lisolette Eder) – not in public and not on screen. He made her into an actress and cast her in over 30 films, always in small, thankless maternal roles. This was his revenge for a “heavy” childhood, a revenge repeatedly reset, like a Groundhog Day bit part.

Most other frequent collaborators were in sexual relationships with him. Golden girl muse Hanna Schygulla was an exception. These entanglements acted as creative fuel and were worked out in thinly-veiled fictions. Fassbinder was partial to dedications. “To him who became Marlene,” begins 1972’s The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant. The “him” is composer Peer Raben, a conquest shunted to the side when Fassbinder fell madly in love with Gunther Kaufman, a seaman-turned-actor, encoded in the film as ‘Karin’, beautiful obsession for the director’s avatar, ‘Petra’.

To add an extra blurred layer to the fact/fiction relationship power games, Marlene – Petra’s mute and verbally abused assistant – was played by Irm Hermann, a secretary Fassbinder turned into an actress. She fell in love with him when they first met in 1965 and did everything within her power to help his fledgling theatre and film career. She raised money, found him work, acted when he asked her to and lived in a position of adoring deference. In return, Fassbinder saved the worst of his off-screen abuses for her (Ryan Gilbey’s recent interview with Hanna Schygulla categorises the most damning aspects) and cast her in roles that showed exactly how little she meant to him.

Hermann was the biggest fall guy for Fassbinder’s preoccupation with “the exploitability of feelings, whoever might be the one exploiting them.” With her narrow governess frame, thin pursed lips and cold eyes, she shuffles through his back catalogue like a prisoner dragging a ball and chain. It is grossly comic how Fassbinder caricatures her with servile roles. Take her introduction in Effi Briest, from 1974. Dressed all in black, she grimaces furiously into a mirror, while her white-clothed mistress Effi (Schygulla) simpers in the background, angelic and happy.

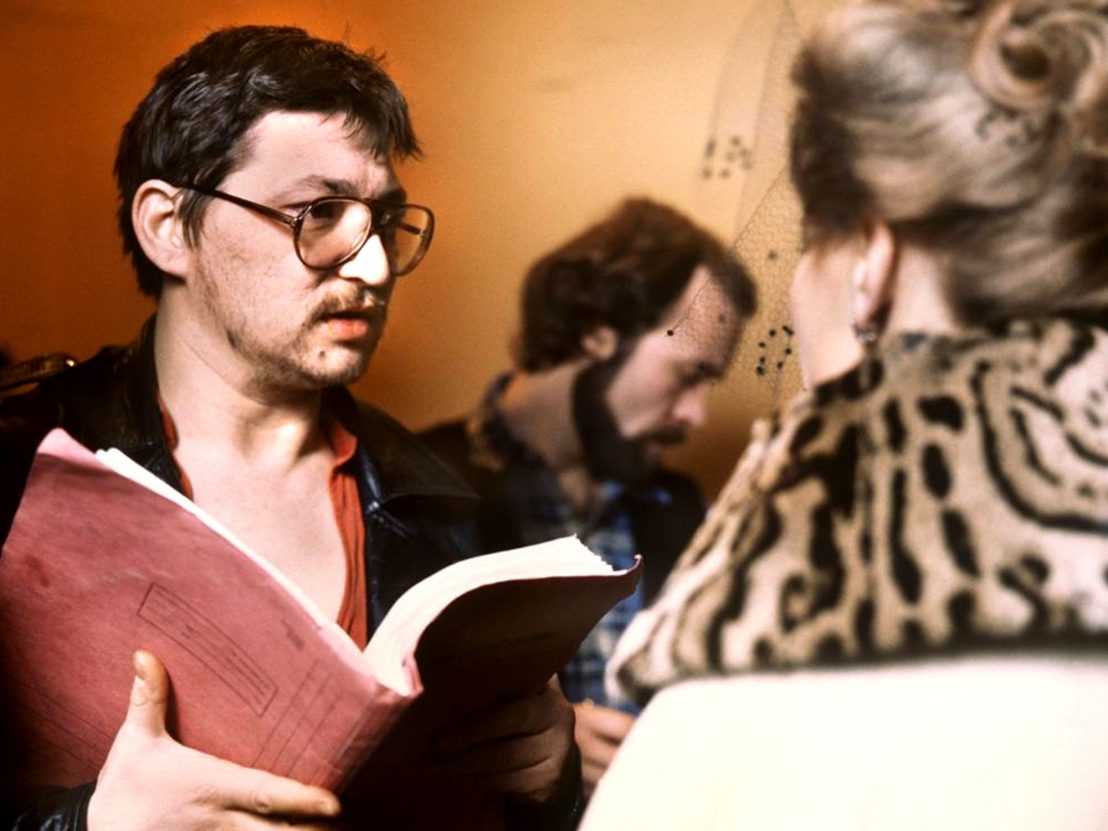

1971’s Beware of a Holy Whore is a gift to those seeking to understand how Fassbinder saw his role as a director. Based on the production troubles of his previous film, Whity, it sees a bullying production manager and a volatile director terrorising the crew as they wait in a Spanish hotel for shooting to begin on film-within-a-film, Patria O Muerte. Fassbinder’s alter egos are usually called Franz (he edited his films under the pseudonym ‘Franz Walsh’), so it is surprising that the director here is called Jeff, although other familiar identifiers are in place. Like our guy, Jeff consumes Cuba Libras with zeal and wears a leather jacket.

The film is a mood piece chronicling an atmosphere of growing anarchy in which sex and fights release tension. Filmmaking is presented as chaos presided over by a loud leader. The most telling lines of dialogue are spoken by characters at opposite ends of the production hierarchy. Jeff has an emotional meltdown towards the film’s end, calling his collaborators “blood suckers”. Earlier, a put-upon crew member mutters to himself, “You can treat me as you like because what you do has quality.” These two lines indicate that Fassbinder found filmmaking maddening and justified unleashing that madness because it advanced his prospects, bringing his collaborators up with him. Before anything else, Fassbinder was a results guy. He placed emphasis on expressiveness, creativity and moving forward. Asked about his extraordinary productivity, he responded, “it must be a special kind of mental illness” and “I am extremely sure of myself.”

In 1992’s Role Play: Women on Fassbinder, an interview-driven documentary featuring Hermann, Schygulla, Margit Carstenson and Rosel Zech, the actors discuss their intense working relationships with the director with piercing ambivalence. Harrowing tales emerge but so too does love. He awoke something inside people, but he didn’t always do it gently or kindly. This was a high-risk strategy. As Carstenson laments, “Rainer was a master of attracting himself to people so that they felt they could not live without him, which unfortunately sometimes happened.”

“The one who loves or loves more is obviously the inferior one in the relationship,” Fassbinder said in a 1978 interview with Peter Jansen, “This is to do with the fact that the one who loves less has more power, obviously. Dealing with this fact – accepting an emotion, or love, or a need – requires a greatness, which most people don’t possess. That’s why things usually get very nasty.” These comments were informed by personal experience, and show why maintaining the whip-hand in relationships was an ongoing interest to Fassbinder. In his head, it was a matter of survival.

In 1978 Fassbinder made what uber-fan Richard Linklater has described as “his most personal film”. Earlier that year, Fassbinder’s third great love, Armin Meier, committed suicide in the pair’s shared apartment while the director was away at the Cannes Film Festival. Fassbinder’s response was In a Year with 13 Moons, which he turned around with typical speed. It is a tender and clear-eyed meditation on loneliness. While not a straight biography, in its DNA it seeks to understand the suicidal impulse. The result is a flabbergasting display of empathy for the deceased.

In a Year with 13 Moons chronicles the quietly spiralling despair of a transsexual named Elvira (Volker Spengler) during the last five days of her life. Imagine It’s a Wonderful Life, but instead of the people of Bedford Falls rallying around George in his moment of need, they turn away – not out of maliciousness, but because of other priorities. There are a handful of unforgettable scenes, several viscerally so, and one that is plain humdrum. Rejected by everyone she has ever loved, Elvira’s final stop is at the door of a journalist who recently interviewed her. She wants company. She needs company, and politely asks if the journalist will come for a beer. He’s game until his wife pointedly reminds him that it’s not a good time. It’s late. He has an early start tomorrow. Turning up at people’s houses is not the done thing.

Respect for conventional behavioural patterns causes the journalist to say no. Elvira leaves alone. A practical social decision from one person happens to be the final rejection for another. The dramatic irony of the scene evokes suicidal depression as a state that cannot make itself known to a person blinkered by ordinary preoccupations. There is a desperate need for sincere engagement and when that is unavailable, interactions are hollow. Elvira’s desperation goes unchecked because people don’t register the severity of loneliness until it’s too late.

So it was with Meier. Through sensitively elevating emotional drama, Fassbinder offered immortality to someone he didn’t take care of in life.

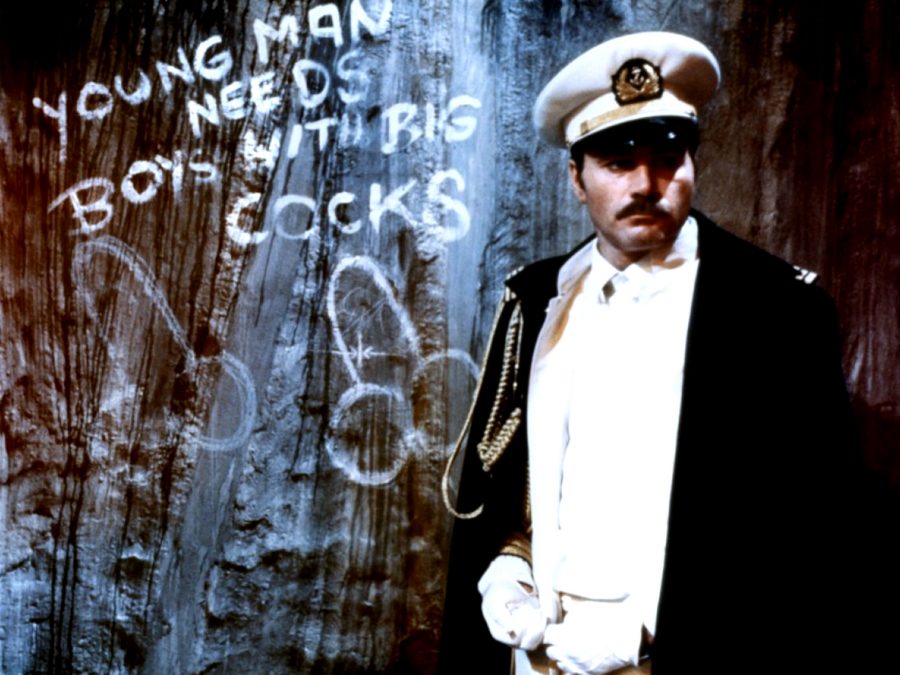

Fassbinder only learned of the suicide of his second great love, El Hedi Ben Salem, five years after the fact, in 1982, the same year his own heart gave out. Salem had non-fatally stabbed two men and fled to France, where he was arrested, hanging himself in his jail cell in 1977. The news of his death was kept from the still emotionally-invested Fassbinder. After finding out, he dedicated his final film, Querelle, to Salem. Their story began in 1971 in a gay sauna in Paris. In opposition to the way he treated Hermann and Pempeit, Fassbinder used cinema to physically idolise his beloved. His 1974 masterpiece Ali: Fear Eats The Soul was Salem’s star vehicle (opposite Brigitte Mira). Many scenes feel like a director salivating over a prize catch. Barely disguised lust motivates a mirror shot of Salem in the shower.

Empires of condemnation could be mounted atop Fassbinder’s shoulders, and the melodramatic details of his persona used as a springboard for psychological dismissals. Fassbinder composed his ravages on celluloid in order that we can still view them. As Schygulla put it: “He was capable of what he demanded of others, of opening himself up completely without hiding behind the mask of sophistication.” This openness is his legacy. It eclipses the lurid misbehaviour that was a part of him by drilling into that very lurid misbehaviour. Fassbinder adds complexity to the moral dilemma of separating art from the artist by building his cinematic reputation through lacerating self-awareness. He did not pretend to be grander or better than the tumultuous nightmare artist that he was.

Where does that leave us and his body of work today? This writer agrees once again with Hanna Schygulla: “I don’t believe that he succeeded in reflecting some universal reality. It was more his own world that he was able to extract from himself.” Yet within Fassbinder we can see shades of ourselves. Inevitably the quality varies across his many works but the masterpieces, the agonised tapestries of personal relationships, are warning shots fired. While I believe that love can be non-exploitative and creative relationships can thrive without power games, there is a part of me that knows how this other way of coexisting would go. This is what makes Fassbinder’s tragic melodramas so recognisable and compelling: they are the twisted parts of our natures given oxygen, they are life through the looking glass.

RW Fassbinder runs at BFI Southbank until May 31. For more info visit bfi.org.uk

Published 5 Apr 2017

An essential viewing guide to the work of this German maestro ahead of a full BFI retrospective.

The German actor reveals how she coped with being Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s muse.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s subversive romantic masterpiece returns ahead of a full BFI retrospective.