Following the recent passing of character actor John Heard, we’ve been reflecting on some of his most memorable performances. Of course there’s Peter McCallister, the forgetful patriarch of the Home Alone series, and we’ve always had a soft spot for the photographer in C.H.U.D., as well as the whiny executive who competes with Tom Hanks in Big (“I don’t get it!”).

Yet nothing quite matches his electrifying turn in 1981’s Cutter’s Way. Based on the novel ‘Cutter and Bone’ by Newton Thornburg, the film opens in true film noir fashion: wannabe gigolo Richard Bone (Jeff Bridges) hazily witnesses a corpse being dumped in a back alley in Santa Barbara. He remains uncertain on the matter, but upon hearing the details, his crippled army buddy Alex Cutter (Heard) is convinced. So much so, in fact, that he promptly takes charge and decides who the murderer is – local tycoon JJ Cord (Stephen Elliott) – and that he should be the one to bring him down.

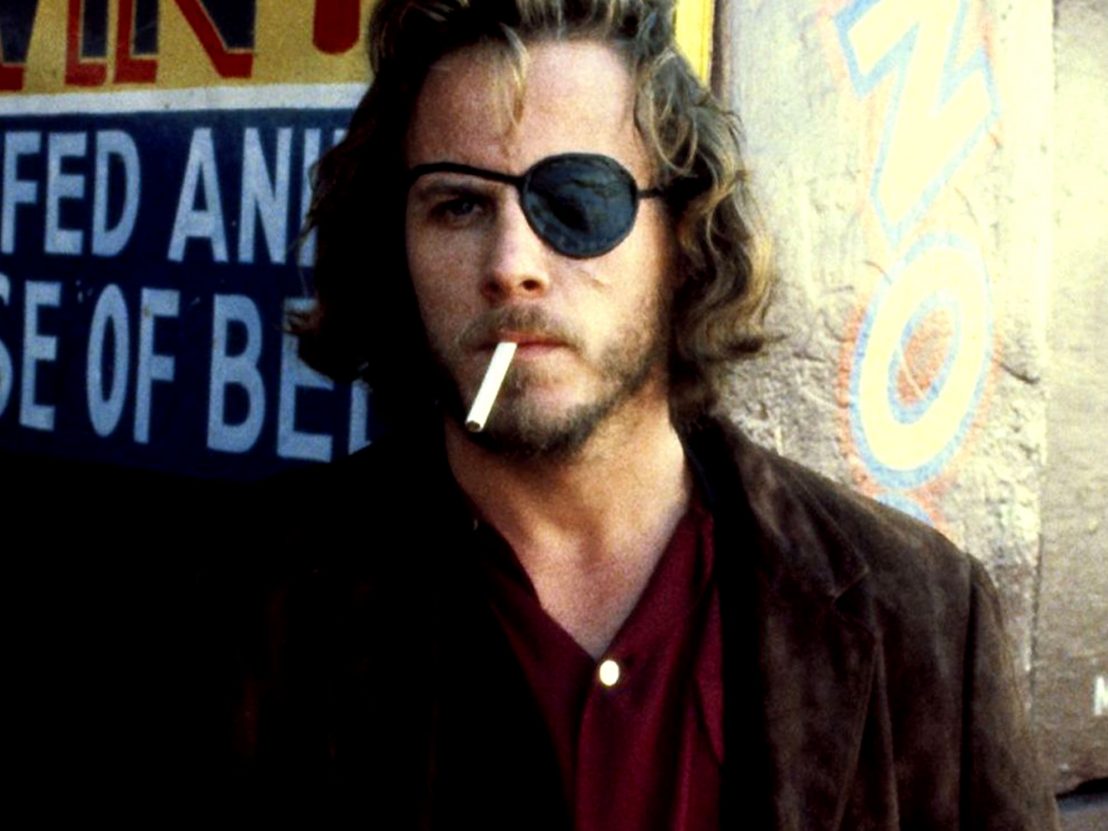

Heard is practically unrecognisable beneath an eyepatch and a scruffy beard. He walks with a cane, save for the nights where he’s too hammered to walk at all, and speaks with the sort of gravely inflection you might associate with Tom Waits. His movements are clunky, exaggerated and a little silly, even for those familiar with Heard’s comedic work. The more we see of Cutter, however, the more apparent it becomes that Heard is using these quirks to disguise a richer, more sorrowful characterisation.

One of Heard’s best scenes actually has little to do with the plot, following Cutter as he drives home in a drunken stupor. Seeing the neighbours’ car blocking his driveway, he promptly smashes it into a pile of scrap metal on their front lawn. Things appear to subside as he stumbles inside, but really, he’s just getting started. He rinses the smell of booze from his mouth, changes into clean clothes, and puts on a sober, apologetic voice for the cops when they arrive. Given his military service, and his appearance, they let him off with a minor violation.

The neighbours are outraged, and Cutter, visibly pleased, proves that the one thing he loves more than booze is screwing people over. It doesn’t matter that they’re blue collar folk like himself; he’s played the victim too long and too often. As he tells Bone later in the film, everyone has a point at which they stop caring about others and start worrying about their piece of the pie. For Cutter, that point is now: “I’m hungry, Rich. I’m fucking starved.”

It’s tough to sympathise with a guy like that. Where Heard succeeds is that he’s able to reconcile Cutter’s pricklier traits; his bigotry, his boozing, his inability to go more than a few words without spewing an insult, with traces of vulnerability that inform these traits.

Director Ivan Passer builds his film around this unraveling performance. He ramps up the mystery and intrigue, only to pull back in pivotal moments, and leave us wondering if there’s really a mystery at all, or if Cutter is simply drowning in his own delusion. The catch is that Cutter doesn’t really care if JJ Cord is guilty or not. To him, Cord (“and every motherfucker like him”) is born guilty, born responsible for the country’s communal suffering and the swandive his own life has taken. It’s this blatant disregard for the truth that makes Heard’s performance so damned tragic. Cutter fancies himself a hero who’s taking on The Man, but really, he’s just searching for something – anything – to justify one last fight.

In a 2016 interview with Movie Geeks Unite!, Heard revealed that the role of Cutter wasn’t far off from his own personality at the time: “I was a real pain in the ass… I was impatient, impolite, I was drinking and very much caught up in the alcoholic lifestyle.” Perhaps it’s because of this (unintentional) method process that Cutter feels more true to Heard than any other role in his career. While he continued to act for decades, he was never again given a chance to explore the complexity and the fast-living mentality he was known for offscreen. (In his written tribute, close friend Daniel Stern added that Heard had “crazy, crazy drink and drug stamina.”)

“What’s this gonna prove?” Bone asks in the film’s devastating climax, “It’s not like it’s gonna change anything.” Cutter sits in silence, perhaps realising his futility for the first and only time. “I gotta go, I go,” he mumbles. It’s the apotheosis of the entire film, and for Heard, a fitting credo for a career-defining performance.

Published 1 Aug 2017

By Ian Mantgani

There’s something deeply entertaining and moving about his widely ridiculed lead turn.

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.

Johnny Depp is on career-best form in Mike Newell’s classic crime-thriller from 1997.